Evidence Notes File 5-B

LAW 6330 (4 credits)

Professor Pedro A. Malavet

5.0 Relevance Revisited, Notes File B

5.5 Character of the Alleged Victim in Sex Offense Cases

The Problems that FRE 412 Addresses

- Former U.F. Law Professor Toni Massaro wrote, as described by our casebook authors:

- "rape is a crime that "few understand," misperceiving "why it occurs, when or where it happens, how it might be prevented, and what effect it has on a victim"; when a claim of rape is met with a claim of consent, "misperceptions about rape play a prominent and documented role in the fact finder's imagination," and a qualified expert who has examined the woman can "help to educate this fact finder in several ways," as by confirming "the existence of trauma consistent with the woman's allegations of nonconsent," helping jurors "understand the psychological cost of rape" and helping "dispel the fact finder's confusion of seduction fantasies with the reality of rape" and helping overcome "traditional disbelief of a complainant who was raped by someone who was not a stranger wielding a weapon in a dark alley".

- Toni Massaro, Experts, Psychology, Credibility, and Rape: The Rape Trauma Syndrome Issue and Its Implications for Expert Psychological Testimony, 69 Minn. L. Rev. 395 (1985). She now teaches at Arizona.

- "rape is a crime that "few understand," misperceiving "why it occurs, when or where it happens, how it might be prevented, and what effect it has on a victim"; when a claim of rape is met with a claim of consent, "misperceptions about rape play a prominent and documented role in the fact finder's imagination," and a qualified expert who has examined the woman can "help to educate this fact finder in several ways," as by confirming "the existence of trauma consistent with the woman's allegations of nonconsent," helping jurors "understand the psychological cost of rape" and helping "dispel the fact finder's confusion of seduction fantasies with the reality of rape" and helping overcome "traditional disbelief of a complainant who was raped by someone who was not a stranger wielding a weapon in a dark alley".

- Malavet

- To put it in simple terms, the traditional appeal to "common sense" in the evaluation of evidence was not working in this area, and this required (1) legislative intervention to change things in the Character area, and (2) allowing expert testimony to educate the trier fact.

- Why is FRE 412 Necessary?

- Judges Were Getting it Wrong

- By Admitting

- Under FRE 404(a)(2)(B)

- Consent Use of

“Sexual Character” Evidence

- Consent Use of

- Under FRE 404(a)(3)

- Credibility use

of “Sexual Character” Evidence

- Credibility use

- Judges Were Getting it Wrong

- Example: Unchastity and Consent

- Nickels v. State (1925)

- “Where ... the defense [to a charge of rape] rests upon the fact of consent, evidence of the general reputation of the [alleged victim] for unchastity, within recognized limits, is competent evidence bearing upon the probability of her consent to the act with which the defendant is charged.”

- 90 Fla. 659, 106 So. 479, 481 (1925).

- Female Chastity and Credibility

- During the 19th Century and Well into 1930s

- Supreme Court of Missouri in 1895

- It is no compliment to a woman to measure her character for truth by the same standard that you do that of a man's predicated upon character for chastity. What destroys the standing of the one in all the walks of life has no effect whatever on the standing for truth of the other. Thus ... it is said: "Adultery has been committed openly by distinguished and otherwise honorable members [of the bar] as well in Great Britain as in our own country, yet the offending party has not been supposed to destroy the force of the obligation which they feel from the oath of office." Dr. Johnson said, in discussing the difference of turpitude between lewdness in a man and in a woman, "that he would not receive back a daughter because her husband, in the mere wantonness of appetite, had gone into the servant girl." And so McCaulay said, respecting the weakness of Lord Byron for sexual pleasure, "that it was an infirmity he shared with many great and noble men,--Lord Somers, Charles James Fox, and others.”

- State v. Sibley, 33 S.W. 167, 168 (Mo. 1895)

- Julia Simon-Kerr, Unchaste and incredible: the use of gendered conceptions of honor in impeachment, 117 YALE L.J. 1854 (2008).

- “Unchaste” Under Florida Law

- “The words “lewd” and “lascivious” mean the same thing and mean a wicked, lustful, unchaste, licentious, or sensual intent on the part of the person doing the act.”

- Fla. Stat. 800.04(6)

- Fla. Supreme Court Standard Jury Instructions 11.10(d)

Casebook

- [CB] Should evidence of the past sexual conduct of the complaining witness be admitted in such cases? Unfortunately the common law tradition answered that question with an emphatic across-the-board yes, which meant that women who brought charges of rape were fair game for cross-examination on their sexual behavior. This sorry sexist tradition had it that such cross-examination bore upon both the credibility o f the woman as a witness and the issue of consent. The underlying hypocrisy was exposed by the facts that such cross-examination was not thought to bear on the credibility of women testifying in other settings, and that in rape trials such cross-examination was permitted even where clinical evidence of physical injury made any suggestion of consent ridiculous.

- [CB] Against this backdrop, "rape shield" statutes were enacted in nearly every state. Congress did likewise by enacting FRE 412, which qualifies FRE 404(a)(2) by restricting the use of evidence relating to the sexual history of a sex crime victim.

Problem 5-J: Ordeal of Leslie or Fred?:

Authors' Answers and Additional Notes, my comments.

- Summary of Analysis

- Relevance?

- Admissibility?

(1) Fred [specific acts with defendant, 412(a)(2), 412(b)(1)(B)]

(2) Greg [Character by Opinion or Reputation, 412(a)(1)]

---(a) Opinion: "Leslie is sexually very active" and

---(b) Reputation: "known as an easy mark"

(3) Thomas [specific act not involving defendant, 412(a)(1)] - Relevance

(a) Argument by Defendant

(b) Counter-Argument by Prosecution

- Authors on Evidential Hypothesis:

- The defense argument is that Leslie's disposition is relevant (whether proved by opinion or reputation) in suggesting that she engages in sex voluntarily, hence that she did so with Fred.

- Compare Aggression/Violence

- Evidence that Vince was disposed toward aggression was seen as relevant in Problem 5-B (Red Dog Saloon - Part II) (page 470) to show he was not a victim of crime (that is, to show that Don acted reasonably in self-defense): Why doesn't the same logic apply here?

- A [] response is that a woman's sexual disposition is irrelevant for the same reason that the charitable generosity is irrelevant in a robbery prosecution.

- Evidence that Vince was disposed toward aggression was seen as relevant in Problem 5-B (Red Dog Saloon - Part II) (page 470) to show he was not a victim of crime (that is, to show that Don acted reasonably in self-defense): Why doesn't the same logic apply here?

- If the disposition of Vince toward belligerence is probative on the question whether he started a fight, why isn't the disposition of Leslie toward sex probative on the question whether she consented with Fred? Surely to some extent disposit.

- Opinion/Reputation for Sex is Less Reliable.

- Second (perhaps paradoxically), opinion and reputation evidence on sexual conduct is likely to be infected with suppositions and speculation, and is peculiarly likely to be distorted in the telling and retelling, hence peculiarly unreliable as an indicator of behavior.

- (1) Specific Instances of Sexual Behavior

- Prior sex with Fred: FRE 412(b)(1)(B) lets Fred describe his one prior sexual encounter with Leslie as evidence of consent. The prosecutor can argue that a single instance a year earlier has little bearing on consent, hence that probative worth is outweighed by the danger of unfair prejudice under FRE 403, but it seems doubtful on these facts that a court would find such proof of specific conduct with the defendant so lacking in probative worth as to warrant exclusion on that ground. And FRE 412(c)(1) requires Fred, if he intends to offer such proof, to make written motion 14 days beforehand, serving notice on both the prosecutor and Leslie.

- (2) & (3) Opinion/Reputation Testimony about Alleged Victim

- Malavet

- It is difficult to conceive of admissibility of "disposition" evidence under FRE 412. The only exception within the rule, that might apply is 412(b)(1)(C).

- Leslie's sexual disposition: Fred will have real difficulty with Greg's testimony, whether cast as opinion or reputation. FRE 412(a) says proof of "other sexual behavior" by the victim is inadmissible, and that proof of the victim's "sexual disposition" is also inadmissible.

- Malavet

- [Exceptions: Only One from 412 MAY Apply]

- Fred would have to argue he is constitutionally entitled to offer this evidence (a possibility acknowledged by FRE 412(b)(1)(C)), but the evidence is probably not so relevant that the Constitution entitles him to offer it. [Notes]

- Malavet

- Non-FRE 412 Exceptions?

Perhaps, see the Doe case in Note 4. Note that 412(b)(1) & (2) allows the use of specific instances of sexual conduct not opinion or reputation.

- Non-FRE 412 Exceptions?

- (4) Prior sex with Thomas:

- Fred claims he had consensual sex with Leslie, and what Thomas says about having sex with her earlier that night could not be admitted to prove she later consented to have sex with Fred. [FRE 412(a)] [FRE 412(b)(1)]

- Arguably, however, FRE 412(b)(1)(A) authorizes the testimony by Thomas if Fred claimed Thomas was the source of the bruises on her legs and forearms.

- Policies Behind FRE 412, as explained by the authors:

- (1) to avoid embarrassing or humiliating complainants in rape cases;

- (2) to encourage (avoid discouraging) victims to report sexual assaults;

- (3) the conviction that judges could not be trusted wisely to exercise discretion to weed out proper from improper questioning of complainants in rape cases.

Notes, [CB]

- Malavet

- 1. I rarely agree with Judge Posner, but I think that he gets it quite right in the quote in note 1. As a general rule, SEX IS NORMAL and engaging in it with one person does not prove that a woman wishes to engage in it with someone else; it does not prove that there was consent even to all sexual encounters with that one person.

- 4. Note that in Doe the court ruled that the offered evidence fell beyond the 412 prohibition rather than fitting within one of its exceptions. Essentially, the evidence that was offered was intended to suggest that the complainant the reputation of being a sort of "military groupie" who engaged in sex with servicemen and men generally around the military base. The court ruled it admissible to show what the defendant knew about the victim's reputation and what effect that would have on his interpretation of her actions as "consent." Tough case. As another note indicates, this was an interlocutory appeal by the alleged victim, I could not find out what happened to the case after this ruling. The ruling certainly would have improved the defendant's chances or getting a favorable plea offer and of mounting a successful defense.

- [Note that in Doe the court ruled that the offered evidence fell beyond the 412 prohibition rather than fitting within one of its exceptions. "The evidence described in items 6 and 7 of the district court's ruling is admissible. Certainly, the victim's conversations with Black are relevant, and they are not the type of evidence that the rule excludes. Black's knowledge, acquired before the alleged crime, of the victim's past sexual behavior is relevant on the issue of Black's intent. See 2 Weinstein and Berger, Evidence P 412(01). Moreover, the rule does not exclude the production of the victim's letter or testimony of the men with whom Black talked if this evidence is introduced to corroborate the existence of the conversations and the letter." Doe, at 12-13.]

- Malavet

- The Doe opinion was issued on an interlocutory appeal by the alleged victim of the trial judge's ruling admitting several types of reputation/opinion and specific acts evidence which followed pretrial evidentiary hearing.

- FROM THE REPORTER:

- "OVERVIEW: Defendant filed a motion to introduce evidence of (1) the victim's general reputation around the Army post where defendant resided; (2) the victim's habit of calling out to the barracks to speak to various soldiers; (3) the victim's habit of coming to the post to meet people and of her habit of being at the barracks at the snack bar; (4) the victim's former landlord regarding his experience with her alleged promiscuous behavior; (5) what a social worker learned of the victim; (6) telephone conversations that defendant had with the victim; and (7) defendant's state of mind as a result of what he knew of her reputation and what she had said to him. The district court allowed all the evidence. The court reversed the judgment in part and held that Fed. R. Evid. 412(a) excluded the evidence in items 1-5 because it was reputation or opinion evidence of the past sexual behavior of the victim. The court affirmed the judgment in part and held that the evidence in items 6 and 7 was admissible because the victim's conversations with defendant were relevant, and defendant's knowledge of the victim's past sexual behavior acquired before the crime was relevant on the issue of defendant's intent."

- [CB Note 7] *** FRE 412 is important in sexual harassment suits. What type of evidence about the complainant in such suits is now likely to be excluded? Note that FRE 412(a) excludes evidence of both the alleged victim's sexual behavior and her "sexual predisposition." What does that mean? Are there ever situations where such evidence will be admitted? See FRE 412(b)(2) (establishing a balancing test).

Problem 5-K: Acting Out on the Assembly Line

- [Basic Framework:]

- The first inquiry asks whether the proof is covered by the exclusionary principle in FRE 412, and the answer is probably yes (the principle covers all four items). In civil cases, however, the bar is not absolute. Admissibility turns on a second and third inquiry.

- The second inquiry focuses on relevance and admissibility under other rules. We think that three of the four proffers are relevant, particularly proof that Haines told a sexually-explicit story (item 3) and made sexually-suggestive remarks to men on the assembly line (item 4), both of which bear on her mental attitude or sensitivities. We think proof that she worked occasionally as an exotic dancer (item 1) is marginally relevant. We think proof of her manner of dress outside the workplace (item 2) is irrelevant and would be excluded for this reason alone.

- The final inquiry asks whether relevance substantially outweighs the danger of unfair prejudice to Haines or harm to her. We think proof of telling a sexually-explicit story (item 3) and making sexually suggestive remarks on the assembly line (item 4) would pass muster, as being more probative than prejudicial or harmful. We think proof of exotic dancing (item 1) presents a close question, but would likely be excluded because risk of prejudice or harm matches or exceeds probative worth.

- (1) FRE 412 covers these proofs.

- Pretty clearly all four proofs are covered by the exclusionary principle because they indicate “other sexual behavior” by Haines or tend to show “sexual disposition.” Working as an exotic dancer (item 1) and manner of dress (item 2) are both viewed as “other sexual behavior (see note 2 after the Problem). Probably the same is true of telling sexually-explicit stories (item 3), especially if they suggest personal experience (sexual activity), and sexually suggestive remarks (item 4), which are like flirting or propositioning (which are within the exclusionary principle). In short, all the items are covered.

- (2) “Otherwise admissible”

- The question of admissibility is something else: Under FRE 412, otherwise-excludable proof may be admitted in a civil case “if it is otherwise admissible under these rules,” and if it survives objections based on “prejudice” or “harm” (taken up separately below). Hence the evidence must at least be relevant (FRE 402 requires as much of all evidence) and it cannot run afoul of any other exclusionary principle, so it must pass muster under FRE 404.

- Are these proofs “otherwise admissible”?

- [IF SO What Unfair Prejudice(s) remain and how does the balance affect admissibility?]

5.6 Character of the Defendant in Sex Offense Cases

Note that FRE 413, 414 & 415 were passed by the Congress over the objection of the Supreme Court and the Advisory Committee, hence, there are not ACNs in this area, just references to the debate in the Senate and House.

Problem 5-L: I Told Him to Stop

- [FRE 413 & FRE 403]

- FRE 403: Despite use of the strong verb "is admissible" in FRE 413, Congress apparently meant to authorize courts to exclude proof of sexual offenses under FRE 403 (such is the clear indication of the legislative comments summarized in the text).

- [General Argument to Admit:]

- Of course FRE 403 is cast in favor of admitting evidence (exclude only if probative worth is "substantially outweighed" by risk of unfair prejudice), and the effect of FRE 413 is to say at least that use of the usually-forbidden character inference ("his prior behavior shows that he is the sort who seeks sex inappropriately, or by force after verbal refusal and physical resistance, so he likely did it again this time") is not itself unfair prejudice. It's a legitimate form of reasoning.

- [General Argument to Exclude]

-

Arguments to exclude must stress that probative worth is low and that the jury is likely

(a) to take the prior instances as proof that Craig is simply a bad person who should be punished (he got away with something in Laura's case, and he committed loathsome acts in N's case) or

(b) to be angered (to "see red" in the sense suggested in the Chapple case on page 83) and be unable reasonably to evaluate the evidence presented in the case.

-

Arguments to exclude must stress that probative worth is low and that the jury is likely

- [Objection Probably Overruled [FRE 413]]

- FRE 413 paves the way for proof of prior acts even when relevance turns on a character inference. (Prior to the adoption of FRE 413, FRE 404(b) disallowed this move. [Note On Some Use] [Note on Defensive Use]) Even under the new regime, however, there are some plausible arguments for exclusion under FRE 403.

- FRE 413: By its terms, FRE 413 invites proof of prior sexual assault offenses (such proof "is admissible") and says it may be considered "on any matter to which it is relevant."

- [FRE 413 and the Assault of Laura: Testimony by the alleged victim of an uncharged assault]

- In the end, we think the incident with Laura is provable. There are obvious similarities between the assault described by Laura and the charged crime (initial intimacy, escalating advances, express verbal refusal, physical resistance leading to assault). One difference between them (what happened with Laura was in her apartment after a movie, where Craig may have thought she would give in) might count in favor of exclusion, but on balance neither this difference nor the other obvious difference (Laura describes verbal refusal leading to assault followed by successful counter-assault; Karin describes verbal refusal leading to assault followed by resistance overcome) seems important. It is easy to see that believing Laura would support the conclusion that Craig is by disposition prone to press for intimacy once he and his date have started down that road, even when she says no and offers physical resistance.

- [Argument for Excluding It]

- One could argue that "one prior misstep" does not establish this trait, and that all a single act can show is something like intent or modus operandi (where there must be enough parallels between the prior and the present case to make the inference plausible on the basis of one act [see Problem 9-F]). If this argument were accepted, the court might exclude proof of what happened to Laura: [The Court might rule that] the assault against Laura and the one charged here are not so factually parallel that they support an inference of modus operandi (as is possible in cases like Casady, described below in this manual) because there are not enough factual parallels to support that inference from one act.

- [The N Incident: Judgment of Conviction, [Compare 609]]

- Probably the incident with N is also provable, although this conclusion is less certain.

- With respect to the conviction for assaulting N, the factual parallels are not impressive. N was a minor and there is no indication of physical aggression overcoming verbal refusal or physical resistance. The parallel is more general -- pursuit of sexual gratification in inappropriate ways (in N's case, pursuing minor daughter of roommate; in Karin's, attacking despite verbal refusal and physical resistance). Apparently the episode in the trailer was an "offense of sexual assault" under FRE 413 (sex with underage victim), and the proof at least supports the character inference that FRE 413 invites: He's done "it" before, so he probably did "it" this time (seek sex inappropriately). But here the counterarguments suggested above (one prior misstep does not show character, and particularized inferences sometimes suggested by prior acts cannot be drawn because dissimilarities are too serious) could be made again. Here they have better chance of success. [FRE 609(a)(1)[B]]

- Malavet

- Note that the defendant intends to testify, therefore, 608 and 609 will be available. Sexual Assault by itself is not a crime involving false statements, but, the circumstances might support such a finding for 608(b) or 609(a)(2) purposes.

- Nevertheless, the admissibility of the conviction for the Assault on N under the reverse-403 standard of FRE 609(a)(1)[B] is going to be difficult given the strong prejudice.

- Note further that under FRE 609 no reference to the underlying facts would be allowed, whereas under 404(b) and 413(a) those facts could be well-developed before the jury.

- The Final question might be if attacks on the victim of rape allowed by FRE 412 might trigger FRE 404(a)(1)[C]. I think that the answer must be no, given the express reference to "allowed under 404(a)" but you might make the argument. On the other hand, because the attack allowed under FRE 412(b) is most likely based on specific instances of conduct, reputation/opinion evidence as to the defendant is unlikely to be allowed in response to attacks on the victim using specific instances.

NOTES

- Note 4. *** See E. Imwinkelried, Uncharged Misconduct §4.16 (1994) (citing studies showing that recidivism is not higher among those convicted of sexual assault than among those convicted of other crimes). [Yet, there appears to be a perception that this is not true, which appears to drive the congressional interest in rules such as 413-415.]

- Malavet

- Note 5. The evidence would most likely be precluded by FRE 412. However, the facts are very similar to the Doe case mentioned in Note 4 at page 493, where that evidence was used to show what defendant KNEW about the victim.

- 6. Is the episode with Laura "another offense" under FRE 413, or does this language require convictions for sexual offenses? Congressional comments indicate that the term "offense" does not require a conviction (raising the question how much these comments count in applying the Rule). [I am not sure that the Supremes will agree, as I said in class, but the Congress would easily amend the rule to apply to conviction and non-conviction as happened with the term "defendant" that was used in FRE 609.]

- Malavet

- NOTE: It is now clear that most circuits do allow evidence of other acts that did not result in a criminal conviction or even a criminal complaint. As long as the acts, if true, would have constituted an offense as defined in 413(d), they may be admitted under 413, 414, and 415. The Supreme Court might rule that "offenses" can only mean convictions for such acts, given the Rehnquist court's textual views, but this seems unlikely, given the prevalent practice in the lower courts.

- This note also asks if this is a FRE 104(a) or 104(b). I am inclined to think that it is 104(a) because the courts dislike it so very much that I would not expect the Supreme Court to apply Huddleston to this scenario. But, that and 50 cents gets you a cup of coffee.

Malavet: A Review of Pertinent Cases

- Given the lower court cases, I am beginning to believe that the factual question will be treated under Huddleston and given to the jury, as long as the legal sufficiency of the argument has been established to the court's satisfaction, and the court believes that there is enough evidence for a reasonable jury to make the factual finding of the occurrence of the offense by a preponderance of the evidence.

- In any case, the Courts of Appeals are just about unanimous in admitting evidence of prior bad acts that did not result in a conviction or even in a complaint under FRE 413, 414, and 415. Therefore, the language of FRE 413(d) needs to be read as allowing the use of prior acts that if charged, could have resulted in a conviction under the federal statutes included in the Rule. The question as to the applicability of 104(b) and Huddleston is not quite as clear.

- Here is a brief overview of the caselaw in the area:

- 104(b) Applies. In Johnson v. Elk Lake School District, 283 F.3d 138, 144-145 (3rd Cir. 2002). In this case, the plaintiff offered evidence of past sexual abuse conduct of an employee co-defendant in her suit against the supervising school district, under FRE 415. The court ruled that the factual questions of whether the acts occurred, whether they constituted sexual offenses and whether they were committed by the school employee, were 104(b) questions to be resolved by the jury, after a minimal threshold finding by the court. This court gave a very expansive interpretation to FRE 415, but nonetheless ruled that if the alleged prior act was not sufficiently specified (supported by reliable evidence) and was similar to the actual offense involved in the case, it should not benefit from the "presumption" of admissibility of FRE 415, and was thus subject to the normal balancing of FRE 403, which resulted in exclusion.

- The Court of Appeals for the Armed Forces agrees with the Third Circuit on the 104(b) question, and explains why the prosecution may wish to use Rule 413 in addition to Rule 404(b)[2]. In a well-crafted opinion, the Court of Appeals for the Armed forces explains the application of Military Rules of Evidence that mirror the language of the Federal Rules of Evidence. The court explained how the prior acts evidence was admissible for certain limited purposes under MRE 404(b)[2], but that the prosecution sought to offer it for the propensity inference under MRE 413. The defendant, on appeal, attacked the constitutionality of 413 under Equal Protection and Due Process grounds. The court rejected both. The court also ruled that Huddleston, and consequently the military equivalent of FRE 104(b), applied to factual questions involving prior acts. U.S. v. Wright, III, 53 M.J. 476 2000 CAAF LEXIS 953 (2000).

- The other circuit cases cited below take a less "presumptive" view of the "sister" rules 413-414 than that adopted by the Third Circuit, and a stronger view in favor of FRE 403 discretion and balancing. It is unclear how they would approach the 104(a) v. 104(b) question, although some might argue that the focus on the court's discretion supports 104(a). In any case, the trial courts held evidentiary hearings without the jury, and sometimes closed to the public, before deciding to admit or to exclude the evidence.

- Due Process/Equal Protection. There have been Due Process and Equal protection attacks on FRE 413 and 414. The Courts of Appeals have rejected them. But, interestingly, the rejection of the constitutional argument is often based on (a) a refusal to interpret 413/414 as a "blank check" and (b) emphasis on the remaining discretion given to the court by FRE 403. Pretrial hearings on admissibility are also favored. See, e.g., U.S. v. LeMay, 260 F.3d 1018 (9th Cir. 2001) (FRE 414 passes constitutional muster; it is subject to balancing under FRE 403); U.S. Mound, 149 F.3d 799 (1998) (FRE 413 constitutional; it IS subject to FRE 403 balancing; hearing closed to public held before evidence was admitted).

- See also Doe ex rel Rudy-Glanzer v. Glanzer, 232 F. 3d 1258 (9th Cir. 2000) (FRE 403 balancing still applies when applying FRE 415; differences in age of VICTIMS made acts too dissimilar to be admitted); U.S. v. Guardia, 135 F.3d 1326 (10th Cir. 1998) (FRE 413 subject to 403 balancing test); U.S. v. Sumner, 119 F.3d 658 (8th Cir. 1998) (FRE 414 subject to FRE 403 balancing test); U.S. v. Larson, 112 F.3d 600 (2nd Cir. 1997) (FRE 414 is subject to FRE 403 balancing).

- Typically, the similarity in the ages of the VICTIMS will establish an adequate pattern; conversely, lack of similarity in ages will destroy the pattern argument. For an interesting factual distinction, however, see U.S. v. Johnson, 2002 US. App. Lexis 25741 (8th Cir. 2002). In a trial for "statutory rape," sexual assault of a minor, in which the defendant was 39 years old and the victim 16, it was error to admit 20-yr.-old prior conviction for assault with intent to rape where the perpetrator was a teenager and the victim was 16. Though the ages of the victims of both assaults were similar, the deciding factor, according to the court of appeals, was the age of the defendant, who was a teenager at the time of the prior offense and an adult in his thirties at the time of the second. The Court correctly believed that FRE 403 required it to balance probative value against unfair prejudice, but erred in applying 413 to the facts of the case (which means that it should not have reached 403); no pattern under 413. The error was not reversible, however, because of other "fair evidence of [the defendant's] guilt."

- See also Jones v. Clinton, 993 F.Supp. 1217 (1998) (district court discusses the admissibility of evidence of sexual contact between former President Clinton and Ms. Monica Lewinsky in Mrs. Paula Jone's case under FRE 415; the court ultimately ordered that the evidence be excluded).

- Rule 413 was tangentially mentioned in a Supreme Court opinion denying a Habeas Corpus petition. Spencer v. Kemna, 523 U.S. 1 (1998).

FRE 413 and Relevance: The casebook authors offer this interesting analysis of what "relevance" might mean under FRE 413.

- It is hard to know what to make of the phrase "may be considered for is bearing on any matter to which it is relevant," which follows and is linked to the phrase "is admissible" in FRE 413 (note 3). One possible construction is that "may be considered" actually authorizes courts to exclude proof of prior sexual offenses because they are sometimes irrelevant, even in sexual offense prosecutions. This conclusion turns on the fact that the phrase apparently recognizes that relevancy questions remain at large and are not totally resolved by FRE 413 itself. Applying this logic in Problem 5-L, the court might exclude the conviction for assaulting N. Another possible construction is that prior sex offenses are always admissible but not always relevant, and the problem with this reading is that it makes no sense to admit irrelevant evidence, and presumably the general principles of FRE 401-402 mean such evidence cannot be considered by the jury. Perhaps a third construction is that the two phrases together ("is admissible" and "may be considered") mean that prior sexual offenses are always relevant in support of the character inference (he did it before, so he probably did it this time), although in particular cases there may be elements of the charged offense that the prior offense does not prove (so the jury cannot take the prior acts as proof of everything necessary to convict in the case at hand). We incline toward the first reading, but perhaps the matter is not quite free of doubt.

- Malavet

- FRE 404(b) Cases: Your casebook authors have collected the following additional sampling of cases that allowed prior sexual assault evidence into the case using FRE 404(b) rather than FRE 413.

- Remember as well to cross-reference Problem 9-F.

-

In our view, these cases suggest that FRE 404(b) was working reasonably well in this setting. Here is the sampling:

- (a) State v. Lough, 889 P.2d 487 (Wash. 1995) (in trial of paramedic for sexual assault, in date situation where allegedly defendant put knockout drug in drink, committed sexual assaults, and neatly folded complainant's clothes before leaving, admitting testimony by four other women describing similar behavior by defendant over 10-year period, to show design or plan).

- (b) State v. Casady, 491 N.W.2d 782 (Iowa 1992) (bench trial for assault with intent to commit sexual abuse in 1989; defendant allegedly asked 13-year-old girl for directions, then tried to pull her in car through passenger-side window; admitting 1979 conviction on guilty plea for kidnapping with intent to terrorize or cause injury, arising out of Missouri incident where defendant struck car driven by 17-year-old victim, then pulled her into his car and drove off and raped her in remote area; also admitting 1976 conviction on nolo plea for assault with intent to inflict bodily injury, arising out of Nebraska incident where defendant sexually assaulted 30-year-old woman after asking her to enter his car and attacking her on the spot when she refused) (given factual similarities, earlier episodes showed intent; remoteness bears on weight; evidence was needed; no jury, so less risk of prejudice).

- (c) State v. Lamoureaux, 623 A.2d 9 (R.I. 1993) (in sexual assault trial, admitting prior episode; defendant met C at club and they danced, drank, talked about family and jobs, and defendant got C to write phone number on napkin because he knew someone seeking a secretary; he persuaded C to drive him home, but grabbed and kissed her when they got where he said he lived; allegedly he became angry and threatening when she resisted, ordering her to take off her clothes and raping her; 9 days before, defendant met L at same bar, and they talked about children, marriage, churchgoing, and L wrote phone number on napkin and agreed to drive him home; on arriving where defendant said he lived, he kissed L and asked her to hug him; he got angry when she pulled away, and pinned her between two front seats, forcing her to touch him; nightgowned woman appeared and defendant fled) (episodes substantially identical; the first showed modus operandi, common design or plan).

- (d) State v. Winter, 648 A.2d 624 (Vt. 1994) (in trial of staff member in group home for patients with mental illness or substance abuse problems, for sexually assaulting patient in her bed, excluding evidence that 4 years earlier while living in another state defendant sexually assaulted his children's 17-year-old babysitter numerous times in his home; earlier episodes too remote, not similar enough to show modus operandi).

- (e) State v. Whittaker, 642 A.2d 936 (N.H. 1994) (in sexual assault trial arising out of incident in which defendant was to give H a ride home in truck after a social visit at home of others, but instead allegedly drove to remote area and forced H to engage in sex on threats that he would "get rough" if she didn't, then prepared to tie her with rope when H made her escape, error to admit proof of incident 5 years earlier with L, who had lived with defendant, in which he drove L to an unfamiliar place, tried to force himself on her, tied her up when she resisted, and engaged in sexual acts) (prior incident might show propensity, which is forbidden, but not plan; nor could it show modus operandi because manner was not unique or unusual enough; nor could it show identity, which was not in issue).

5.7 Habit and Routine Practice

Malavet: An Opening Note

- Initially, let me caution you against over-reading FRE 406.

- 406 can in theory be read much too broadly. Apply an extremely healthy amount of skepticism to this rule, especially when criminal conduct or conduct that raises moral overtones is involved.

- The four descriptions of habit evidence [described by our authors] emphasize that [FRE 406]

- (a) habits involve nonvolitional behavior (descriptions like "reflex," "semi-automatic," "regular if not invariable" come to mind),

- (b) habits involve "specific situations" and "particular kind of situation,"

- (c) character is more "general" (a "tendency" applicable to "all the varying situations of life"), and

- (d) character involves "moral overtones" that are not part of our notion of habit.

- While repetition is crucial to classification as habit, I cannot emphasize enough the effect of "moral overtones" in classifying the matter as character evidence rather than habit or routine practice. To allow to 406 to trump general or specific character prohibitions too generally would completely undue the effect of 404(a), 404(b)[1] and especially 412. That is not the intent of the rule. Therefore, the rule must be tempered by the strong policies underlying the prohibition rules, especially when dealing with conduct that can be evaluated, fairly or unfairly, as having strong moral overtones, such as criminality and sexuality.

- Handle with care

- You have to be careful with the facts in the problems. The evidence of habit or routine practice is often required because of what you LACK, i.e., you have no other evidence to prove the facts suggested by habit or routine practice. In Problem 5-M, all the witnesses to the auto accident were dead. In Problem 5-N Halleck must have been unwilling to admit and perhaps even totally denied that he heated the cylinders. It is often like an episode of Columbo (or, for the younger crowd, Criminal Intent), everyone in the audience knows who did it and exactly how they did it, but at trial the criminals intend to deny everything (or admit nothing). And in Problem 5-O the government had to prove beyond a reasonable doubt an element of the crime, and no one could testify to having actually served the defendant.

Problem 5-M: Death on the Highway:

Authors' Answers and my comments.

- [ Relevance.]

- On facts like these, defendants routinely plead contributory negligence and plaintiffs hope to get to the jury on a theory of per se negligence -- car entering a highway and turning left is at fault almost by definition if a collision ensues. And the situation could support application of res ipsa loquitur: This sort of accident seldom happens unless the entering driver was negligent, and he is prima facie negligent. But if circumstances support an inference that the driver on the highway was negligent (speeding, being in the wrong lane), then evidence that he exercised due care is important.

- [Form of Proof.]

- Should Budge or Frese be permitted to testify that Teel is "a good, careful driver"? Probably not: Evidence of carefulness or carelessness (even when connected to driving a car) is not considered habit. Rather, it amounts to character or disposition under FRE 404 (excludable when offered to prove behavior in civil case). The result seems sound because the generality of the proof means that it is worth little.

- [What Might Be Admissible?]

-

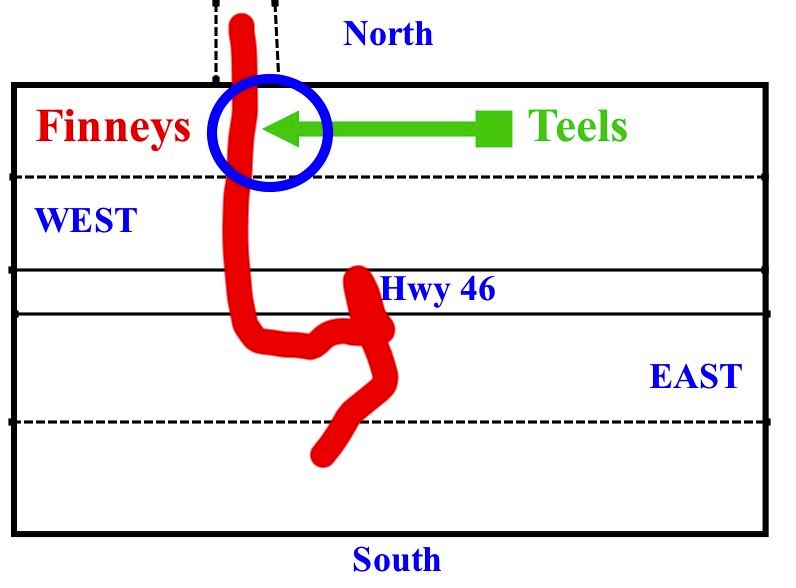

It would be different if Budge or Frese could testify that Teel drives Route 46 every day, that they regularly drive with him, and that invariably Teel drives at or below the speed limit, and never strays over the center stripe. See Barton case (note 3, page 430).

The problem tracks a decided case, but with one critical difference. In the problem the proffered testimony is that Lance Teel is a "good, careful driver," but in the actual case the witnesses testified expansively, and the court approved habit evidence about the man driving the car on the highway that included

-

It would be different if Budge or Frese could testify that Teel drives Route 46 every day, that they regularly drive with him, and that invariably Teel drives at or below the speed limit, and never strays over the center stripe. See Barton case (note 3, page 430).

- [Case Example: Admissible]

- (a) testimony by one witness that she had ridden with him and "thought he was a good driver who did not drive over the speed limit but usually drove five miles per hour under the limit," and

- (b) testimony by another that decedent "was a good driver, cautious, obeyed the rules of the road" and "never drove over 60 miles per hour" (speed limit being 70 MPH):

- [T]estimony regarding the deceased's care in driving, his practice of driving under the speed limit, and his regard to the rules of the road is testimony which devolved into specific aspects of the deceased's conduct. Such testimony showed more than a general disposition to be careful and showed a regular practice of meeting a particular kind of situation with a specific type of conduct. The testimony is all the more cogent because of the lack of an eyewitness account. Frase v. Henry, 444 F.2d 1228, 1232 (10th Cir. 1971) (quoted in the text at page 428 on definition of habit). The court was careful to say that proof that decedent "was a careful, cautious man" would not be admissible because it would not be "specific enough" to tend to prove he was "careful in a specific instance in specific circumstances." Not surprisingly, the court found for plaintiff (estate of driver on highway).

Problem 5-N: The Burning Sofa:

Authors' notes with my comments.

- Girard should be allowed to testify: While both smoking and drinking are in some senses conscious and volitional, they seem for many people to be at best quasi-conscious acts, to some extent beyond or outside volition, or at least sufficiently so to be viewed as semi-automatic. Particularly the combination seems to be powerful, and drinking beer or alcohol in other forms leads in an immediate and compelling way, for very many people, to smoking as well. In any event, Girard’s task is not to establish that drinking reflects habit – we know from clinical evidence that Girard was drinking – but to establish that smoking while drinking was habitual with Rollins. Girard’s foundation (“four or five incidents” in the last year when drinking and dropping a cigarette led to damage) seems sufficient to show habitual overconsumption of alcohol in combination with careless smoking. The judge resolves the question of sufficient instances as a matter of admissibility under FRE 104(a) (issue is raised in note 2 after the Problem).

- The Problem rests on Sams v. Gay, 288 S.E.2d 822 (Ga. App. 1982), where the reviewing court concluded that plaintiff could indeed testify: ...

Superseded old Problem: The Exploding Can (p. 436, of the 6th edition)

Facts

I transcribe the facts from the old edition.

- Forest Halleck worked as a mechanic who specialized in the repair and maintenance of automobile air conditioning systems. One day after replacing the compressor unit in a vehicle, he began to charge the new unit in the usual way by injecting a pressurized liquid refrigerant (Freon). Mter two cans flowed into the unit without difficulty, he encountered problems with the third and fourth cans. He filled an empty two-pound coffee can with warm water to raise the temperature and pressure of the smaller can of refrigerant, but as he warmed the fourth can it exploded and injured him seriously.

- Halleck sued Lorton Chemicals (maker of the Freon), which defended on the basis that Halleck was negligent in ignoring warning labels on the can.

- At trial, Lorton sought to prove that Halleck habitually used an immersion heater to raise the temperature of the water in the coffee can and that the explosion was caused when the temperature went above 130 degrees (the maximum safe temperature, as noted on the can). It called Mike Newsome, a fellow worker who was prepared to testify that he had often seen Halleck use an immersion coil to heat water, and thus to heat cans of Freon.

- Halleck objects that the evidence is "barred by the rule against character evidence." Should Newsome be allowed to testify?

Authors' Answers, with my notes

- [Halleck's objection should be overruled:]

- Newsome's testimony describes behavior that is specific and (if not subconscious) at least semi-automatic. Thus it qualifies as habit under FRE 406. Perhaps the real question is whether testimony that Halleck "often" used the warming technique is enough to show habit. In part, the answer may turn on how many times Newsome observed Halleck: If the two have worked together for quite a while (weeks at least) and "often" means "daily" or "many times a week," Newsome's testimony is sufficient and should be admitted. In part, the answer turns on how long Halleck has been changing freon and how much of his time is spent doing that: If he has been in the business for quite a while (months or years) and spends much of his time (a tenth, quarter, a half) changing freon, then a few "sample" observations are sufficient and Newsome's testimony should be admitted.

- Malavet

- Be careful in reading the language "a few 'sample' observations." If it means that the witness was sufficiently familiar with the actor's conduct, then he or she may limit their testimony to describing a few sample observations. On the other hand, a few sample observations might be a proper foundation for the testimony, IF they are sufficiently reliable (e.g., he always did it that way under the same circumstances, as we discussed in class). Note that this also comes up when evaluating the witnesses' competence (FRE 601) and personal knowledge (FRE 602). Actual Case: Specific Inference of Conduct

- [The Actual Case]

- The problem tracks a New York case, which held that the trial court erred in excluding the evidence. The reviewing court noted that "New York courts have long resisted allowing evidence of specific acts of carelessness or carefulness to create an inference that such conduct was repeated when like circumstances were again presented," but thought that "proof of a deliberate and repetitive practice" was different: Far less likely to vary with the attendant circumstances, such repetitive conduct is more predictive than the frequency (or rarity) of jumping on streetcars or exercising stop-look-and-listen caution in crossing railroad tracks. Under no view, under traditional analysis, can conduct involving not only oneself but particularly other persons or independently controlled instrumentalities produce a regular usage because of the likely variation of the circumstances in which such conduct will be indulged. Proof of a deliberate repetitive practice by one in complete control of the circumstances is quite another matter and it should therefore be admissible because it is so highly probative.

- As previously noted, Halloran, in the course of his work as a mechanic, had serviced "hundreds" of automobile air conditioners and had used "thousands" of cans of Freon. From his testimony at trial it seems clear that in servicing these units he followed, as of course he would, a routine. If, indeed, the use of an immersion coil tended to be part of this routine whenever it was necessary to accelerate the flow of the refrigerant, as he indicated was often the case, the jury should not be precluded from considering such evidence as an aid to its determination.

- Of course, to justify introduction of habit or regular usage, a party must be able to show on voir dire, to the satisfaction of the Trial Judge, that he expects to prove a sufficient number of instances of the conduct in question . . . . If defendant's witness was prepared to testify to seeing Halloran using an immersion coil on only one occasion, exclusion was proper. If, on the other hand, plaintiff was seen a sufficient number of times, and it is preferable that defendant be able to fix, at least generally, the times and places of such occurrences, a finding of habit or regular usage would be warranted and the evidence admissible for the jury's consideration.

- Halloran v. Virginia Chemicals, Inc., 361 N.E.2d 991, 995-996 (N.Y. 1977).

NOTES [CB]:

- Malavet

- All the notes are important. But let me just comment on the cases that I think are simply wrong.

- Note. 1. *** Physically abusing or threatening someone? Compare Brettv. Berkowitz,706A.2d 509,516 (Del.1998) (in sexual misconduct and malpractice suit against lawyer, excluding proof that he had "prior relations with clients") with State v. Huerta, 947 P.2d 483, 490 (Mont. 1997) (in trial of boyfriend of victim's mother, evidence that she abused child, offered to show she was source of his injuries, qualified as habit, but court could exclude under FRE 403).

- Both of these cases are in my mind and in your authors' minds wrong. They should be 404(b) cases, not 406 cases.

- Note further the new 2000 case resolved in Maryland.

Problem 5-O: Was he Served (the exception that proves the rule?):

Authors' Answers, with my notes.

- [In General]

- Organizational routine supports an inference that it was followed in a particular instance, and such proof could support the inference here. Probative worth depends not on individual proclivities, but on supervision and authority, guidelines and manuals, attitudes and pressures that develop in a workplace. Such proof is more readily admitted than evidence of individual habit, perhaps because organizational routine seems more regular and more probative than personal habit.

- Does a person who does not himself follow the routine have the necessary knowledge? The answer is yes if he has observed it firsthand and understands how it works, meaning he has seen people or machines performing their functions and understands the underlying purposes and relationships.

- [Is it Admissible under these facts?]

- But Lesher apparently has not observed service of the sort of papers involved here. And where understanding depends largely on what the witness has heard from others, the situation is troubling. If he has heard "what goes on" from several people in a position to know and has corroborative firsthand knowledge about organizational practices, circumstantial knowledge might be all right. It generally suffices when a party offers business records under FRE 803(6) (see chapter 4).

- On these facts, Lesher seems to fall below a reasonable minimum. If he had some firsthand corroborative information (seeing many deportations where organizational routine was followed, and many cases where the person who dealt with Gutierrez served the deportee), then he would be an adequate witness. Short of offering such a basis in the knowledge of Lesher, the government should produce a witness who serves warrants to describe how it is done, or at least one who has observed warrants being served.

- [The Actual Case: Admit]

- The problem tracks a case that approved such testimony. The court conceded that the agent could not testify about "out-of-court statements of detention officers as to the procedures followed at deportations," and could not satisfy the personal knowledge requirement by "reliance on inadmissible hearsay." Still the court thought it was sufficient that the agent had extensive experience in "the normal rule of things and the normal processes of deportation," and was thus "familiar with the procedure." United States v. Quezada, 754 F.2d 1190, 1195-1196 (5th Cir. 1985) (government had other proof, including defendant's thumbprint on back of warrant, which makes it look very much as though he was served; other parts of the legend on the warrant also indicated service, since the officer apparently filled out the time and place of service).

- NOTES:

- [CB] 5. Should proof of industry practice be admitted on the question of standard of care? See Avena v. Clauss & Co., 504 F.2d 469, 472 (2d Cir. 1974) (custom of moving bales by inserting longshoremen's hooks under the bands to move packages, admissible to prove intended use, hence dangerous condition). [Your authors think this is about standard, not conduct. I am not so sure.] And sometimes it bears on the interpretation of contracts. See M/V American Queen v. San Diego Marine Construction Co., 708 F.2d 1483,1491 (9th Cir. 1983) (custom and practice regarding limits of liability in ship repair). Are these uses regulated by FRE 406? [NO.] This evidence provides context for contract interpretation not for conduct. Could it be Admissible?

5.8 Subsequent Remedial Measures

While some arguments for exclusion might be made under the traditional approach of FRE 401, 402 and 403, the fact is that it is unlikely that evidence of subsequent remedial measures would be held to be inadmissible in the absence of FRE 407. In any case, FRE 407 reflects some concerns about relevance, probative value and unfair prejudice/confusion, etc. Nevertheless, the ultimate reason for rules like this one are policy concerns usually legislative policy concerns.

Rule 407. Subsequent Remedial Measures

- [CB] The exclusionary doctrine rests on policy, relevance, and confusion of issues. As a matter of policy, it is thought wise to avoid discouraging efforts to make things better or safer (hence furthering an aim completely "extrinsic" to the conduct of litigation). Also it is considered unfair to introduce against a person, over his objection, evidence that he behaved responsibly after the fact. Concerns over relevancy arise because efforts to prevent future accidents may not show or even indicate that past practice or conditions amounted to negligence or fault. Concerns over confusion of issues arise partly because of the relevancy problem and partly because it may be impossible even to show that changes that follow an accident were made because of the accident.

- [CB] Three major issues arise in the application of FRE 407. First, does the exclusionary doctrine apply in product liability cases? (Any question on that point was resolved by a 1997 amendment to FRE 407, which expressly says the exclusionary doctrine does apply here, but many states do not apply the exclusionary doctrine in this setting.) Second, does the Erie doctrine require federal courts to follow state practice on subsequent measures? (The bulk of modern authority says no, but the matter is still open to debate. And as noted above, federal law conflicts with many state rules in product liability cases.) Third, when may subsequent [507] measures be shown to prove "feasibility"? (FRE 407 so permits if that point is "controverted," but what does "controverted" mean?)

- Malavet

- I suppose that, as Ms. Hall suggested, we might be more concerned about allowing defendants to hide their failure to take precautionary measure SOONER behind FRE 407 than with creating incentives to remedy the problem after the accident (that is what "feasibility" is intended to prevent). This is a tough call, especially when viewed through the lens of the informational disadvantage of plaintiffs in personal injury cases. Nevertheless, in defense of the Rule, we might say that once an accident has occurred we might as well help prevent a future one by creating the privilege. On the other hand, changing protocols ought to occur not because of a fear of liability, but out of concern for public safety. I think that the CDC's changing view of Anthrax exposure is motivated by concerns about the public health, not by fear of liability. But, the reality is that we as a society make cost/benefit analysis, some involving lives, every day.

Case: Tuer v. McDonald

I think that Tuer needs to be read in the context of medical malpractice's standard of care. Essentially, were the actions of the doctor objectively reasonable at the time he took them, even if as a result of the death of Mr. Tuer they re-evaluated the protocols and their underlying risk-benefit analysis.

On the other hand, in a products liability case the question usually is "Could you have designed better?" This is why applying the rule to products cases is controversial.

In the DuPont case, as I mentioned in class, the Plaintiffs were allowed to argue that the building could easily have been designed originally with an additional fire escape within the casino. Since the casino lacked such an independent fire escape, and the fire had engulfed the only avenue of escape --the lobby area-- the casino patrons were trapped. (This was not an FRE 407 situation because the building had not yet been remodeled, but it would certainly have been a feasibility argument if remodeling with a new exit had occurred by the time of the trial).

Elevators also present many feasibility-of-retrofitting arguments. Many old controls, for example, were activated by heat, thus opening the elevator precisely where there was a fire, with tragic (and gruesome) results. Otis Elevator has long offered new controls that are NOT activated by fire, but many customers argue that the cost of retrofitting is too high.

Look at any old building on our campus and you will notice safety retrofits.

- [CB] [The Subsequent Measure]

- After Tuer's death, and apparently because of it, St. Joseph changed its protocol with respect to discontinuing Heparin for patients with stable angina. Under the new protocol, Heparin is continued until the patient is taken into the operating room.

- [The FRE 407 Issue]

- [CB] Defendants made a motion in limine to exclude any reference to the change in protocol under Maryland Rule 5407. Plaintiff countered that (a) the change was not a remedial measure because the defense claimed the prior protocol was correct, and (b) she was entitled to prove the change to show that continuing Heparin was "feasible." The trial court rejected the first argument (saying that defendants did not have to admit wrongdoing in order to claim that a change was remedial), but ruled that it would admit the proof if defendants denied feasibility.

- [CB, middle of the paragraph] Plaintiff got Dr. McDonald to say that under no circumstances would a patient in Tuer's condition (unstable angina stabilized by Heparin) continue on Heparin to the time of surgery. He considered restarting the Heparin when surgery was postponed, but decided against it. The court sustained a defense objection to the question whether it was "feasible to restart Heparin," but plaintiff got McDonald to say that restarting it would have been unsafe.

- Malavet

- It is interesting that court seems willing to read Dr. McDonald's statements as saying "Given my medical knowledge and experience, at the time prior to Mr. Tuer's death, I considered it unsafe to restart Heparin."

- [CB] Plaintiff argued that she was entitled to prove the change in protocol, to impeach and to show it was not unsafe to restart Heparin, but the court disagreed. [FRE 407] On cross, McDonald testified that he would have restarted Heparin if Tuer had developed new chest pains indicating unstable angina, pointing out that Heparin is used later in CABG surgery to prevent clotting as blood circulates through a heart-lung machine. [FRE 611(b)] [FRE 611(c)]

- [CB] Two doctors testified for plaintiff that Tuer had unstable angina and failing to restart Heparin departed from the customary standard. Three testified for defendant that it was right not to restart Heparin, since Tuer had stabilized.

- Tuer: FEASIBILITY [CB]

- Rule 5-407(b) exempts subsequent remedial measure evidence from the exclusionary provision of Rule 5-407(a) when it is offered to prove feasibility, if feasibility has been controverted. [FRE 407] That raises two questions: [1] what is meant by "feasibility" and [2] was feasibility, in fact, controverted?

- [CB] *** Some courts have construed the word narrowly, disallowing evidence of subsequent remedial measures under the feasibility exception unless the defendant has essentially contended that the measures were not physically, technologically, or economically possible under the circumstances then pertaining. Other courts have swept into the concept of feasibility a somewhat broader spectrum of motives and explanations for not having adopted the remedial measure earlier, the effect of which is to circumscribe the exclusionary provision. [FRE 407]

- [Feasibility NOT Controverted]

- [CB] Courts in the first camp have concluded that feasibility is not controverted -and thus subsequent remedial evidence is not admissible under the Rule- when a defendant contends that the design or practice complained of was chosen because of its perceived comparative advantage over the alternative design or practice ([citing cases]); or when the defendant merely asserts that the instructions or warnings given with a product were acceptable or adequate and does not suggest that additional or different instructions or warnings could not have been given ( [citing cases] ); or when the defendant urges that the alternative would not have been effective to prevent the kind of accident that occurred ( [citing cases] ).

- [Feasible AND Controverted]

- [CB] Courts announcing a more expansive view have concluded that "feasible" means more than that which is merely possible, but includes that which is capable of being utilized successfully. In Anderson v. Malloy, 700 F.2d 1208 (8th Cir. 1983), for example, a motel guest who was raped in her room and who sued the motel for failure to provide safe lodging, offered evidence that, after the event, the motel installed peepholes in the doors to the rooms. The appellate court held that the evidence was admissible in light of the defendant's testimony that it had considered installing peepholes earlier but decided not to do so because (1) there were already windows next to the solid door allowing a guest to look out, and (2) based on the advice of the local police chief, peepholes would give a false sense of security. Although the motel, for obvious reasons, never suggested that the installation of peepholes was not possible, the court, over a strident dissent, concluded that, by inferring that the installation of peepholes would create a lesser level of security, the defendant had "controverted the feasibility of the installation of these devices." [Court describes other cases.]

- Malavet

- A situation similar to the motel case is found in every apartment complex in Gainesville. As a result of the Rollin case (the murder of five young people in Gainesville) and the payment of damages by apartment complexes to the families of the victims, most Gainesville complexes now prominently advertise peepholes, security locks, alarms and policies giving discounts to law enforcement officers who live in the complex. All these are, potentially, subsequent remedial measures.

- [CB, end of paragraph] defendants often are willing to stipulate to feasibility in order to avoid having the subsequent remedial evidence admitted.

- [The Big Question: Is it Feasible OR it IS feasible (possible) but not recommended.]

- [CB] The issue arises when the defendant offers some other explanation for not putting the measure into effect sooner -often a judgment call as to comparative value or a trade-off between cost and benefit or between competing benefits- and the plaintiff characterizes that explanation as putting feasibility into issue.9 To the extent there can be said to be a doctrinal split among the courts, it seems to center on whether that kind of judgment call, which is modified later, suffices to allow the challenged evidence to be admitted.

- [CB] *** That does not, in our view, constitute an assertion that a restarting of the Heparin was not feasible. It was feasible but, in their view, not advisable.

- [Tuer: IMPEACHMENT []]

- [CB] The exception in the Rule for impeachment has created some of the same practical and interpretive problems presented by the exception for establishing feasibility. [Testimony] [FRE 407]

- [CB] If the defendant is asked on cross-examination whether he thinks that he had taken all reasonable safety precautions, and answers in the affirmative, then a subsequent remedial measure can be seen as contradicting that testimony." [Testimony] [FRE 407] 1 Saltzburg, Martin, and Capra, [Federal Rules of Evidence Manual 487 (6th ed. 1994)].

- [CB] *** Thus, as Saltzburg, Martin, and Capra point out, most courts have held that subsequent remedial measure evidence is not ordinarily admissible for impeachment "if it is offered for simple contradiction of a defense witness' testimony." 1 Saltzburg, Martin and Capra, supra, at 487.

- [CB] *** In Muzyka v. Remington Arms Co., 774 F.2d 1309, 1313 (5th Cir. 1985), for example, where a defense witness asserted that the challenged product constituted "perhaps the best combination of safety and operation yet devised," a design change made after the accident but before the giving of that testimony was allowed as impeachment evidence, presumably to show either that the witness did not really believe that to be the case or that his opinion should not be accepted as credible. [Testimony] [FRE 407] In Dollar v. Long Mfg., N.C., Inc., 561 F.2d 613 (5th Cir. 1977), the court allowed evidence of a post-accident letter by the manufacturer to its dealers warning of "death dealing propensities" of the product when used in a particular fashion to impeach testimony by the defendant's design engineer, who wrote the letter, that the product was safe to operate in that manner.

- [CB] Consistent with the approach taken on the issue of feasibility, however, subsequent remedial measure evidence had been held inadmissible to impeach testimony that, at the time of the event, the measure was not believed to be as practical as the one employed, or that the defendant was using due care at the time of the accident.

- [CB] *** It is clear that Dr. McDonald made a judgment call based on his knowledge and collective experience at the time.... The only reasonable inference from his testimony . . . was that Dr. McDonald and his colleagues reevaluated the relative risks in light of what happened to Mr. Tuer and decided that the safer course was to continue the Heparin. That kind of reevaluation is precisely what the exclusionary provision of the Rule was designed to encourage.

- Malavet

- Again, as a standard of care case, Tuer is not troubling, but as to FRE 407, it is a tough case, especially on impeachment.

- The only impeachment that the court appears willing to allow would be if Dr. McDonald denied that the protocol had been changed, or, if he were stupid enough to testify that he would "not do anything different today"! On feasibility, it appears that the court would require the defendant to argue that it would have been impossible to give Heparin, in order to trigger the feasibility exception.

- BTW, the reason why it is unlikely that the hospital could have been held liable is that the Doctors are usually independent contractors rather than employees of the hospital. Thus, the doctors' actions do not expose the Hospital to liability because the doctors are usually not considered to be agents or employees of the hospital. This is a tough substantive reality. The hospital might be held liable if a nurse employed by the hospital applied the wrong protocol or applied the protocol incorrectly. Also, in a teaching hospital, the interns and students may be hospital employees.

5.9 Settlement & Plea-Bargaining Negotiations

- 1. Civil Settlements [CB]

- [CB] FRE 408 bars proof of civil settlements, offers to settle, and "conduct or statements made" during settlement negotiations, when offered to prove "liability for or invalidity of the claim or its amount." In part this exclusionary principle rests on concerns of relevancy: **** The major underlying reason for the rule is public policy: The system would grind to a halt if every case filed were tried, yet lawyers would not be able to risk negotiating if what they said or did in trying to settle were later provable if the attempt to settle failed.

Rule 408. Compromise and Offers to Compromise

Problem 5-P: Potato Problems:

Authors' Answers with my comments.

- [Admit/Objection Overruled:

[(1) No Controversy as to Amount and

[(2) Pre-Dispute]- Sosbee's statements are admissible because FRE 408 applies only to claims that are "disputed as to either validity or amount," and Sosbee speaking for Cheron disputes neither validity nor amount. In short, the exclusionary principle does not apply to pre-controversy statements. What Sosbee said cannot be taken as admitting the damages are what Perrin claims: Perrin stated no figure and Sosbee agreed to none; what Sosbee conceded is liability.

- [Actual Case:]

- The problem tracks the facts in a real case, where the court thought the statements were admissible:

- The policy rationale which excludes an offer of settlement arises from the fact that the law favors settlements of controversies and if an offer of a dollar amount by way of compromise were to be taken as an admission of liability, voluntary efforts at settlement would be chilled. That, however, is not the situation we find in the language used by Sosnovske. Instead, he was in effect stating that the herbicide was sold to you on the basis that it would aid, not substantially destroy, your crop and the company is prepared to stand in back of the basis of the sale. The dollar amount was, of course, left open but that did not make the statements of the company's position with regard to backing up its product an offer of compromise and settlement. Perzinski v. Chevron Chemical Co., 503 F.2d 654, 658 (7th Cir. 1974).

NOTES: Civil Settlement

I have simplified the notes on civil settlements to reflect the clarity of the 2006 amendments and the restyling of the rule.

- Notes on FRE 408 p. 462

- Make No Admissions

- Unless you are absolutely certain that the privilege applies (Note 1).

- Privilege Applies to Partial Settlement

- Partial settlement between passenger and one of two drivers is covered, Note 2 Example

- Exceptions: FRE 408(b)

- If settling passenger is called as witness he may be cross-examined (Note 2).

- For what purposes? To Show Bias

- Compare Note 2 to Note 3

- Settlement with possibly-negligent driver also covered (Note 3).

- Double Recovery Otherwise Limited

- Notice may be required

- Judge is generally given right to avoid double recovery in proportionality recovery jurisdictions

- Note insurance subrogation. (Note 3).

- Impeachment Use Prohibited

- FRE 408 expressly amended to prohibit impeachment by prior inconsistent statement or contradiction (Note 4).

Problem 5-Q: This is Criminal: You Can't Exclude Civil Settlements Here

AUTHORS' NOTES:

- Heart of the Matter.

- The beginning point is to recognize that the exclusionary principle in FRE 408 does reach certain aspects of civil settlements when offered even in later criminal cases. That FRE 408 carries this meaning – and there is no doubt that it does – is a little surprising, given the language in the Rule. Thus FRE 408(a) says that the exclusionary principle blocks use of civil settlements to prove “liability for” or “invalidity of” or the “amount” of any disputed “claim,” and in criminal trials we do not ordinarily speak of “claims” or “liability” or “amount.” In criminal cases we speak instead of “charges” and “defenses” and “guilt” or “innocence.” Still, the 2006 amendment makes it clear that the terms in the rule (“liability for” or “invalidity of” a “claim”) must refer to charges and defenses in criminal cases because of the exception that the 2006 amendment created in FRE 408(a)(2). There we find that “statements” in civil settlement negotiations relating to “a claim by a public office or agency in the exercise of its regulatory, investigative, or enforcement authority” can be used “in a criminal case” after all. This exception would make no sense if the exclusionary principle didn’t apply in criminal cases, so the applicability of FRE 408 in criminal cases is a good place to begin.

- (1) Prince’s payment of the civil fine.

- Since the exclusionary principle in FRE 408 applies in criminal cases, and since it reaches “furnishing” some “valuable consideration” and since FRE 408(a)(1) recognizes no exception that could apply, proof of Prince’s payment of the civil fine in settlement is excludable. In paying the fine, Prince did “furnish” a “valuable consideration” in compromise of what presumably would have been civil claims that Prince violated Indiana’s Blue Sky laws. The ACN to the 2006 amendment suggests that offering or accepting a compromise “is not very probative of the defendant’s guilt” in a later criminal case. We quote this language in note 4 after the Problem. Hence proof that Prince paid the fine is excludable.

- (2) Prince’s statements admitting misconduct.

- The transcript of the conversation containing Prince’s admission that he made personal use of more than $1.5 million raised from investors is not excludable. The reason is that FRE 408(a)(2) creates an exception to coverage for “statements made” in settlement talks “when offered in a criminal case” and when the talks “related to a claim by a public office or agency in the exercise of its regulatory, investigative, or enforcement authority.” Here what Prince said to Rachel Sanders on behalf of the Indiana Attorney General clearly did involve a regulatory claim brought by a public agency. The ACN to the 2006 amendment says that when someone “makes a statement in the presence of government agents, its subsequent admission in a criminal case should not be unexpected,” and that one can “protect against subsequent disclosure” by “negotiation and agreement” with the civil regulator, which suggests that the ACN thinks that one can negotiate the terms of settlement talks so as to exclude statements by the defendant. Again we quote the relevant language for students in note 4 after the Problem. Perhaps so, although we don’t know of any cases in which that has happened. What seems more likely is that attorneys in this setting will do all the talking, and that they will speak in “hypothetical” or “suppositional” terms, as was the custom before FRE 408 came into being (note 1 on page 449). Apparently the Justice Department insisted that statements made by defendants [remain admissible].

Notes on Civil Settlement in Criminal Cases

- Note 1: Privilege Generally

- Privilege applies to criminal cases generally

- Note state variations

- Note 2: Fines

- Fines are covered by privilege of FRE 408(a)(1)

- ACN expressly discuss low probative value

- Note 3: Criminal Case Admissions

- Admissible under FRE 801(d)(2) and

- Not covered by FRE 408

- Not privileged by FRE 410

- Except nolo contendere

- Note 4: Compare 408(a)(2) Cases

- United States v. Peed (4th Cir. 1983)

- Admit statement as attempt to avoid prosecution where “negotiation” setup by investigators and defendant asked private party to “drop charges”

- United States v. Davis (D.C. Cir. 2010)

- In prosecution of defendant for stealing funds from fraternity, reversible error under FRE 408 to admit evidence of defendant’s offer to fraternity’s treasurer to pay half of $29,000 of disputed checks to settle fraternity’s claim.

- United States v. Peed (4th Cir. 1983)

5.10. Plea-Bargaining in Criminal Cases

Read FRE 410

Read also Federal Rule of Criminal Procedure 11 on Pleas

Read a DOJ Standard Plea Sample

Problem 5-R: "I used his stuff": Confession or Bargaining--My lawyer is an idiot:

Authors' Answers, with my comments

- [The Problem: Do you need an AUSA?]

-

Any argument for exclusion must first deal with the language of FRE 410(a)(4), which reaches only statements made in "discussions with an attorney for the prosecuting authority." If the apparent limits of the language can be overcome, the task is to develop a test that distinguishes plea bargaining from confessions.

Terminology problem. FRE 410(a)(4) implies that the absence of Amy Norton disposes of the defense argument: The Rule simply does not reach what Rackly told the agents. But the ACN (quoted in note 4) makes clear the framers' intent not to occupy the whole field on this point: The revised language in the Rule "does not compel the conclusion" that statements to law enforcement agents "are inevitably admissible," particularly if agents "purport to have authority to bargain."

-

Any argument for exclusion must first deal with the language of FRE 410(a)(4), which reaches only statements made in "discussions with an attorney for the prosecuting authority." If the apparent limits of the language can be overcome, the task is to develop a test that distinguishes plea bargaining from confessions.

- [Confession or Plea Bargaining?]

- The cases suggest FRE 410(a)(4) excludes defendant's statements to a law enforcement agent if (a) the agent has actual authority to bargain and is doing so, or (b) defendant thinks bargaining is occurring and his belief is reasonable under the circumstances.

- Here Rackly can advance both these arguments, though he will probably lose. First, he can argue the agents have actual authority to bargain because (i) the second meeting continued the original efforts to reach agreement and Norton herself was involved in those, and (ii) the Agents appear at a second meeting which defense counsel Slavin set up in his call to Norton's office.

- But the problems are that (a) Norton disclaimed any interest in bargaining in the first meeting (said she wasn't ready), (b) the agents came to the first meeting as well as the second and did not purport to have authority either time, and (c) they had another purpose both times (gathering information and usable evidence, as indicated by the fact that they Mirandized Rackly).