Evidence Notes File 4-B

LAW 6330 (4 credits)

Professor Pedro A. Malavet

4.0 Hearsay Exclusions and Exceptions (File 2)

4.05 Hearsay: Admissions by Employees & Agents

Introduction for your Review

- Remember to review the material for Chapter 3. [Go there]

- You might also want to test yourself by doing the hearsay quiz in your book. [Go there]

- Though presumptively excludable (FRE 802), there are, as your authors note, 37 express exceptions allowing the use of hearsay within the rules, not to mention the six "non-truth use" categories that we discussed. This might beg the question, why have a hearsay rule at all? Well, we need something to put on the test.

- Remember that we discuss three major categories of Not-Hearsay:

- (1) Nonhearsay

not within the definition

[FRE 801(c)(2)] - (2) “Not Hearsay”

exclusions from the definition by (Congressional) fiat; hearsay, but not really

[FRE 801(d)(1) & FRE 801(d)(2)] [FRE 802] - (3) “Exceptions”

hearsay but admissible

[FRE 802] [FRE 803] [FRE 804] [FRE 805, 806, 807]

- (1) Nonhearsay

Deconstructing Hearsay:

- On our Initial Look at Hearsay, ask:

- Preliminarily: FRE 104(a) or FRE 104(b)

- Remember that whether or not the hearsay was heard by the witness is a 104(b) question; hence all the self-serving testimony that is subjected mostly to technical hearsay testing under the Rules.

- (1) Is the offered evidence relevant? [FRE 401] [FRE 402]

- (2) Is the offered evidence hearsay? [FRE 801, et seq.]

- (a) Does the evidence fit within the definition of hearsay of FRE 801(a),(b)&(c)?

- Remember the Non-Truth Uses

- If "no", go to 403, if "yes" the evidence is presumptively inadmissible under FRE 802[a] unless FRE 802[b] leads to an exemption or exception.

- (b) Even though it fits the 801(a),(b),(c) definition of hearsay, is it nevertheless within some exclusion that expressly defines it as "not-hearsay" or "nonhearsay" [FRE 801(d)]?

- (c) Even though it fits the 801(a),(b),(c) definition of hearsay, AND despite it failing to be exempted by 801(d), is it nevertheless within some exception found in the rules, especially in FRE 803 and 804?

- (a) Does the evidence fit within the definition of hearsay of FRE 801(a),(b)&(c)?

- (3) Should the offered evidence be excluded, despite being relevant, and regardless of the answer to the hearsay question? [FRE 403]

- The initial part of the chapter provides a very good description of what we will cover for the rest of the semester.

Let me emphasize that for exam purposes the analysis must be complete. Let me use today's case to illustrate:

Deconstructing Hearsay:

- Preliminarily, is the question for the judge or for the jury? [FRE 104(a); FRE 104(b)]

- Remember that the question of whether the statements were made/heard is a 104(b) question.

- In Mahlandt the court rules that the issue of foundation (does it meet the requirements of FRE 801(d)(2)(D)?) is for the court to decide, along with the other matters.

- This refers to the factual elements of 801(d)(2)(D), employment relationship, scope of employment and the temporal requirement that it be made during the employment.

- (1) Is the offered evidence relevant?

- [FRE 401] [FRE 402]

- In Mahlandt statements regarding how the child's wounds were inflicted were highly relevant.

- Evidential Hypothesis: If the party thinks and or states that the wolf bit the child, that has a strong tendency to show that fact of consequence (the wolf, which was under the control of the declarant-party-agent, bit the child) more likely than not.

- Therefore, the evidence is relevant and thus admissible under FRE 402.

- (2) Is the offered evidence hearsay?

[FRE 801, et seq.] [Presumptively Excludable FRE 802]- (a) Does the evidence fit within the definition of hearsay of FRE 801(a),(b)&(c)?

[Remember the Non-Truth Uses (which, by definition means they do NOT fit within 801(c))] - In Mahlandt two were written (the note and the minutes) and one was an oral statement intended by the parties to convey the message "[we think that] the wolf bit the child." FRE 801(a).

- In Mahlandt the statements were made by persons. Mr. Poos is the declarant as to the first two, the author of the minutes, probably the corporate secretary, in any case, a person prepared the minutes. FRE 801(b).

- In Mahlandt the (FRE 801(c)) Statements, (FRE 801(c)(1)) were made by the declarant outside of his court testimony, and (FRE 801(c)(2)) are being offered by the plaintiffs to prove the truth of the matter asserted, i.e., that the wolf bit the kid. 801(c).

- The statements are thus Presumptively Excludable under FRE 802.

- (a) Does the evidence fit within the definition of hearsay of FRE 801(a),(b)&(c)?

- (b) Even though it fits the 801(a),(b),(c) definition of hearsay, and the presumption of inadmissibility of FRE 802, is it nevertheless within some exclusion that expressly defines it as "not-hearsay" or "nonhearsay"

[FRE 801(d)]?- In Mahlandt the court rules that the two statements by Mr. Poos fit within the language of FRE 801(d)(2)(D): They were made by an employee because Poos is employed by defendant (this appears to be uncontroverted here); the statements regarded matters within the scope of the employment (he is the wolf-keeper and the wolf was actually in his care in his own home, for business-related reasons--the classroom visits); and they were made during a period when he was employed by defendant company.

- The minutes are authorized statements under FRE 801(d)(2)(C) but only admissible against the Center, not against Mr. Poos. (Here you might be able to use corporate law and the rules of the corporation to your advantage, by showing that the corporate secretary prepared the minutes, and that the corporation authorized them; corporate minutes are often "published" to the board and then "approved" by them; alternately, under applicable law or corporate by-laws, a corporate officer is responsible for taking notes of what happens at the meetings.

- (c) Even though it fits the FRE 801(a),(b),(c) definition of hearsay, AND despite it failing to be exempted by 801(d), is it nevertheless within some exception found in the rules, especially FRE 803 and 804?

- In Mahlandt you do not need to reach this question, because of the answer to the previous part.

- (3) Should the offered evidence be excluded, despite being relevant, and regardless of the answer to the hearsay question? [FRE 403]

- In Mahlandt the court notes that 403 exclusion is possible, but highly unlikely. Only as to the minutes, admissible against one party, but not against the other, does the level of unfair prejudice justify exclusion.

- However, as we discussed especially in relation to Problem 4-F (the use of pleadings), the other reasons for exclusion under FRE 403, are available under appropriate circumstances (confusion of the issue, misleading, cumulative, etc.). But, speaking generally, forcing a party to explain its own words will almost NEVER rise to the level of unreasonable or unfair prejudice when you are applying the admissions doctrine.

- The effect of a limiting instruction [FRE 105] comes into play here to reduce unfairness.

Casebook Notes on Employee Admissions

- [CB] A company hiring a truck driver intends that he will operate the truck, not speak for the company. In this situation notions of relevancy and substantive principles of agency would not pave the way to admit against the company what the truck driver says, and for years the common law of evidence excluded such statements. But where such an employee injures another in the course of his duties, it came to be seen as unfair that an employer legally liable for the tort might remain evidentially immune from the statements of the tortfeasor.

- [CB] Multiple or "Layered" hearsay.

Government Employees:

- [CB] Government Admissions. *** Traditionally statements by public employees have not been admissible against the government, on the grounds that (1) such people do not have the same sort of personal stake in the outcome of any dispute as private employees have, and (2) agents cannot bind the sovereign. ***

- [CB] There are no easy answers here, but modern decisions question the traditional result and point toward a wider rule of admissibility. See United States v. Kattar,840 F.2d 118,130-131 (1 st Cir.1988) (in criminal case, government is defendant's party-opponent; that does not necessarily mean "the entire federal government in all its capacities" fits this category, but Justice Department does; on behalf of defendant, court should have admitted sentencing memorandum and brief filed in other cases) (invoking adoptive admissions doctrine); United States v. Morgan, 481 F.2d 933, 938 (D.C. Cir. 1978) (decisions like Pandilidis may not have survived; nothing in Rules indicates intent to put government beyond reach of agent's admission doctrine).

Case: Mahlandt v. Wild Canid Research Center

A case like Mahlandt illustrates the nature of the admissions doctrine and its central tenet, which I will encapsulate simply as:

A party to litigation should be required to explain his/her/its own words in court.

That is what FRE 801(d)(2) is about.

Note that BOTH Kenneth Poos AND his employer are parties to this action. Therefore, you must distinguish admissibility against each of them.

- [CB] This is a civil action for damages arising out of an alleged attack by a wolf on a child. ***

- [Are they admissible against Mr. Poos? The authors explain that]

- Clearly the statements by Kenneth Poos are admissible against him. FRE 801(d)(2)(A) permits use of a statement against the person who made it regardless whether he acts in "his individual or a representative capacity," so it does not matter that Poos apparently spoke as agent for the Center.

- [CB] [Statement 1]

- Within an hour after he arrived home, Mr. Poos went to Washington University to inform Owen Sexton, President of Wild Canid Survival and Research Center, Inc., of the incident. Mr. Sexton was not in his office so Mr. Poos left the following note on his door:

Owen, would [you] call me at home, 727-5080? Sophie bit a child that came in our back yard. All has been taken care of. I need to convey what happened to you. - [Denial of admission of this note is one of the issues on appeal.]

- Within an hour after he arrived home, Mr. Poos went to Washington University to inform Owen Sexton, President of Wild Canid Survival and Research Center, Inc., of the incident. Mr. Sexton was not in his office so Mr. Poos left the following note on his door:

- [CB] [Statement 2]

- Later that day, Mr. Poos found Mr. Sexton at the Tyson Research Center and told him what had happened. Denial of plaintiff's offer to prove that Mr. Poos told Mr. Sexton that, "Sophie had bit a child that day," is the second issue on appeal.

- [CB] [Statement 3]

- A meeting of the Directors of the Wild Canid Survival and Research Center, Inc., was held on April 4, 1973. Mr. Poos was not present at that meeting. The minutes of that meeting reflect that there was a "great deal of discussion . . . about the legal aspects of the incident of Sophie biting the child." Plaintiff offered an abstract of the minutes containing [245] that reference. Denial of the offer of that abstract is the third issue on appeal.

- [Bites or Scratches?]

- [CB] Daniel had lacerations of the face, left thigh, left calf , and right thigh, and abrasions and bruises of the abdomen and chest. Mr. Mahlandt was permitted to state that Daniel had indicated that he had gone under the fence. Mr. Mahlandt and Mr. Poos, about a month after the incident, examined the fence to determine what caused Daniel's lacerations. Mr. Mahlandt felt that they did not look like animal bites. The parallel scars on Daniel's thigh appeared to match the configuration of the barbs or tines on the fence. The expert as to the behavior of wolves opined that the lacerations were not wolf bites or wounds caused by wolf claws. Wolves have powerful jaws and a wolf bite will result in massive crushing or severing of a limb. He stated that if Sophie had bitten Daniel there would have been clear apposition of teeth and massive crushing of Daniel's hands and arms which were not injured. Also if Sophie had pulled Daniel under the fence, tooth marks on the foot or leg would have been present, although Sophie possessed enough strength to pull the boy under the fence.

- [The Exclusion]

- [CB] The jury brought in a verdict for the defense.

- [CB] The trial judge's rationale for excluding the note, the statement, and the corporate minutes, was the same in each case. He reasoned that Mr. Poos did not have any personal knowledge of the facts, and accordingly, the first two admissions were based on hearsay; and the third admission contained in the minutes of the board meeting was subject to the same objection of hearsay, and [also] unreliability because of lack of personal knowledge.

- [CB] The notes of the Advisory Committee on the Proposed Rules, discuss the problem of "in house" admissions with reference to Rule 801(d)(2)(C) situations. This is not a (C) situation because Mr. Poos was not authorized or directed to make a statement on the matter by anyone. But the rationale developed in that comment does apply to this (D) situation. Mr. Poos had actual physical custody of Sophie. His conclusions, his opinions, were obviously accepted as a basis for action by his principal. See minutes of corporate meeting. As the Advisory Committee points out in its note on (C) situations,

- Malavet

- I highly recommend that you read the entire ACN on 801(d)(2). It is really emphatic about NOT caring about reliability in general, just that the words came out of the mouth of a party or their representative.

- [Exemptions or Exclusions vs. Exceptions]

- [CB] Rule 805 recites, in effect, that a statement containing hearsay within hearsay is admissible if each part of the statement falls within an exception to the hearsay rule. Rule 805, however, deals only with hearsay exceptions. A statement based on the personal knowledge of the declarant of facts underlying his statement is not the repetition of the statement of another, thus not hearsay. It is merely opinion testimony. Rule 805 cannot mandate the implied condition desired by Judge Weinstein.

- [CB] *** Nor does Rule 403 mandate the implied condition desired by Judge Weinstein.

- [CB] Thus, while both Rule 805 and Rule 403 provide additional bases for excluding otherwise acceptable evidence, neither rule mandates the introduction into Rule 801(d)(2)(D) of an implied requirement that the declarant have personal knowledge of the facts underlying his statement. So we conclude that the two statements made by Mr. Poos were admissible against Wild Canid Survival and Research Center, Inc.

- [CB]As to the entry in the records of a corporate meeting, the directors as primary officers of the corporation had the authority to include their [247] conclusions in the record of the meeting. So the evidence would fall within 801(d)(2)(C) as to Wild Canid Survival and Research Center, Inc., and be admissible. The "in house" aspect of this admission has already been discussed, Rule 801(d)(2)(D), supra.

But there was no servant, or agency, relationship which justified admitting the evidence of the board minutes as against Mr. Poos.

- [FRE 403 Discretion [Hearsay]

- [CB] There is left only the question of whether the trial court's rulings which excluded all three items of evidence are justified under Rule 403. ***

- [CB] So here, remembering that relevant evidence is usually prejudicial to the cause of the side against which it is presented, and that the prejudice which concerns us is unreasonable prejudice; and applying the spirit of Rule 801(d)(2), we hold that Rule 403 does not warrant the exclusion of the evidence of Mr. Poos' statements as against himself or Wild Canid Survival and Research Center, Inc.

- [CB] But the limited admissibility of the corporate minutes, coupled with the repetitive nature of the evidence and the low probative value of the minute record, all justify supporting the judgment of the trial court under Rule 403.

NOTES [CB]

The notes are substantially updated to reflect the very latest caselaw.

Your casebook authors explain the Cedeck vs. HBE problem succinctly, and I concur: “The decisions in EEOC v. HBE and Cook (note 2) seem right, and Cedeck seems decidedly wrong.”

Problem 4-H: I was on an errand for my boss

- Authors’ Answers, with my comments and questions in brackets

- [Can the statement constitute proof of agency?]

- [Who makes the decision, the judge or the jury?]

- [Is there enough proof of agency in this problem? What evidence is there?]

- [What about the admission of negligence?]

- [Can the driver's statement prove agency? Yes, but only partially.

It is certainly proof of agency].- It was once clear that the answer was No (this fact had to be proved entirely by independent evidence). Now we know that the answer is Yes: The statement itself does count as proof that the speaker was an agent and that his job responsibilities include whatever the statement describes, although at least some additional proof is required. [FRE 801(d)(2) last]

- [Explanation:]

- The tide turned when the Supreme Court decided Bourjaily (upholding use of a coconspirator statement in deciding whether a conspiracy existed between the speaker and the defendant, but stopping short of saying that the statement alone could suffice to prove the point, see page notes in the casebook).

- And of course FRE 801(d)(2) was amended in 1987 (after Bourjaily). Now the last sentence of that provision states: "The contents of the statement may be considered but are not alone sufficient to establish . . . the agency or employment relationship and scope thereof under subparagraph (D)."

Heart of the Matter.

- [Two Statements:

[(1) Scope of Employment

[(2) Admission of Negligence]- In substance, Rogers says two things. First, he is employed for Farmright and was acting in the scope of his employment ("making a delivery") at the time of the accident. Second, he was probably negligent (he was "distracted" at the time).

- [The Judge Decides

[(1) As a matter of Foundation?

[(2) As a matter of Conditional Admissibility?

[Pick no. 1.]- Traditionally the judge determines predicate facts (declarant was an agent of defendant speaking on matters within the scope of his duties), but only for purposes of determining admissibility, and this practice survived enactment of the Rules. The judge determines predicate facts to answer "[p]reliminary questions" on "the admissibility of evidence" under FRE 104(a). If she makes these determinations favorably to the plaintiff, the statement comes in.

- She says nothing to the jury about her conclusions because the jury will have to resolve the same issues in deciding the case on the merits. If the judge decides the predicate facts against the plaintiff, the case might still go to the jury (there may be enough other proof of negligence and agency to support findings favorable to plaintiff), and again the judge does not advise the jury of her findings.

- [Is there enough additional proof of employment on the facts of the problem?]

- Yes, in the form of the legend on the side of the truck, which courts often treat as "raising a presumption" that the truck belonged to the company identified on the legend. (Arguably, of course, the legend itself is hearsay, but accepting it as essentially "prima facie" evidence - enough to require rebuttal - makes sense in the same way that accepting a label on a can of peas that says "Jolly Green Giant" makes sense. See FRE 902(7).

- [Negligence]

- But this part of the statement (declarant was negligent) does not assert a point that must be proved to make the statement admissible.

- Malavet

- Let me emphasize that the negligence statement is admissible against the company both because of respondeat superior (which makes it relevant) and because of FRE 801(d)(2)(D), because there is enough evidence for the court to conclude that; (1) it was given by an employee, (2) about a matter within (he is a truck driver!), and (3) the driver was then still employed by the company (unlikely he had been fired in the intervening 30 minutes).

4.06 Hearsay: Co-Conspirator Statements

- [CB] The elements in the exception have not changed since then, and they are set out in FRE 801(d)(2)(E): Coconspirator statements are admissible if

- (1) declarant and defendant conspired ("coventurer" requirement), and the statement was made

- (2) during the course of the venture ("pendency" requirement) and

- (3) in furtherance thereof ("furtherance" requirement).

- [CB] Clearly the conversations in Inadi have nonhearsay significance: The fact that alleged co-offenders had such a conversation, coupled with the tenor of their comments, suggest a conspiracy in action, even without taking the assertions as proof of the facts they assert. As such they are nonhearsay "verbal acts." But the conversations also have hearsay significance: One speaker asserts a circumstantially relevant fact (Inadi set up the bust), which tends to implicate him in the conspiracy. And arguably the other implies (intends to communicate) that Inadi is one of their number (he is not an informant).

- (d) Statements That Are Not Hearsay. A statement that meets the following conditions is not hearsay:

- (2) An Opposing Party’s Statement. The statement is offered against an opposing party and:

- (A) was made by the party in an individual or representative capacity;

- (B) is one the party manifested that it adopted or believed to be true;

- (C) was made by a person whom the party authorized to make a statement on the subject;

- (D) [1] was made by the party’s agent or employee [2] on a matter within the scope of that relationship and [3] while it existed; or

- (E) [1. Coventurer] was made by the party’s coconspirator [2. Pendency] during and [3. Furtherance] in furtherance of the conspiracy.

- — The statement must be considered but does not by itself establish

- [1] the declarant’s authority under (C);

- [2] the existence or scope of the relationship under (D);

- [3] or the existence of the conspiracy or participation in it under (E).

Case: Bourjaily v. U.S.

- [Procedure for Co-Conspirator Statements]

- [CB] Before admitting a co-conspirator's statement over an objection that it does not qualify under Rule 801(d)(2)(E), a court must be satisfied that the statement actually falls within the definition of the rule. There must be evidence that there was a conspiracy involving the declarant and the nonoffering party, and that the statement was made "in the course and in furtherance of the conspiracy." [The Court quotes FRE 104(a).] Petitioner and respondent agree that the existence of a conspiracy and petitioner's involvement in it are preliminary questions of fact that, under Rule 104, must be resolved by the court. The Federal Rules, however, nowhere define the standard of proof the court must observe in resolving these questions.

- [CB: Standard of Proof for the Preliminary Factual Questions?]

- We are therefore guided by our prior decisions regarding admissibility determinations that hinge on preliminary factual questions. We have traditionally required that these matters be established by a preponderance of proof. Evidence is placed before the jury when it satisfies the technical requirements of the evidentiary Rules, which embody certain legal and policy determinations. The inquiry made by a court concerned with these matters is not whether the proponent of the evidence wins or loses his case on the merits, but whether the evidentiary Rules have been satisfied. Thus, the evidentiary standard is unrelated to the burden of proof on the substantive issues, be it a criminal case, see In re Winship, 397 U.S. 358 (1970), or a civil case. See generally Colorado v. Connelly, 479 U.S. 157 (1986). [FRE 104(a)] The preponderance standard ensures that before admitting evidence, the court will have found it more likely than not that the technical issues and policy concerns addressed by the Federal Rules of Evidence have been afforded due consideration. *** Therefore, we hold that when the preliminary facts relevant to Rule 801(d)(2)(E) are disputed, the offering party must prove them by a preponderance of the evidence.

- [What Proof is Required to Meet the Preponderance Standard?

[(a) Independent evidence, or

[(b) The statements themselves (which raises the bootstrapping problem)?]- [CB] Even though petitioner agrees that the courts below applied the proper standard of proof with regard to the preliminary facts relevant to Rule 801(d)(2)(E), he nevertheless challenges the admission of Lonardo's statements. Petitioner argues that in determining whether a conspiracy exists and whether the defendant was a member of it, the court must look only to independent evidence -that is, evidence other than the statements sought to be admitted. Petitioner relies on Glasser v. United States, 315 U.S. 60 (1942), in which this Court first mentioned the so-called "bootstrapping rule."

- ["Bootstrapping"]

- [CB] [S]uch declarations are admissible over the objection of an alleged coconspirator, who was not present when they were made, only if there is proof aliunde that he is connected with the conspiracy.... Otherwise, hearsay would lift itself by its own bootstraps to the level of competent evidence.

- [Plain Meaning of FRE 104(a)[2]]

- [CB] Petitioner claims that Congress evidenced no intent to disturb the bootstrapping rule, which was embedded in the previous approach, and we should not find that Congress altered the rule without affirmative evidence so indicating. It would be extraordinary to require legislative history to confirm the plain meaning of Rule 104. The Rule on its face allows the trial judge to consider any evidence whatsoever, bound only by the rules of privilege. We think that the Rule is sufficiently clear that to the extent that it is inconsistent with petitioner's interpretation of Glasser and Nixon, the Rule prevails.

- [CB: Are the Statements Reliable?]

- Nor do we agree with petitioner that this construction of Rule 104(a) will allow courts to admit hearsay statements without any credible proof of the conspiracy, thus fundamentally changing the nature of the co-conspirator exception. Petitioner starts with the proposition that coconspirators' out-of-court statements are deemed unreliable and are inadmissible, at least until a conspiracy is shown. Since these statements are unreliable, petitioner contends that they should not form any part of the basis for establishing a conspiracy, the very antecedent that renders them admissible.

- [The statements MAY be reliable enough]

- [CB] Petitioner's theory ignores two simple facts of evidentiary life. First, out-of-court statements are only presumed unreliable. The presumption may be rebutted by appropriate proof. See FRE 803(24) [Now FRE 807] (otherwise inadmissible hearsay may be admitted if circumstantial guarantees of trustworthiness demonstrated). Second, individual pieces of evidence, insufficient in themselves to prove a point, may in cumulation prove it. The sum of an evidentiary presentation may well be greater than its constituent parts. Taken together, these two propositions demonstrate that a piece of evidence, unreliable in isolation, may become quite probative when corroborated by other evidence. A per se rule barring consideration of these hearsay statements during preliminary factfinding is not therefore required. Even if out-of-court declarations by co-conspirators are presumptively unreliable, trial courts must be permitted to evaluate these statements for their evidentiary worth as revealed by the particular circumstances of the case. *** If the opposing party is unsuccessful in keeping the evidence from the factfinder, he still has the opportunity to attack the probative value of the evidence as it relates to the substantive issue in the case. See, e.g., FRE 806 (allowing attack on credibility of out-of-court declarant).

- [Totality Analysis:

[Statements AND other Evidence = Conspiracy (and other elements) = Admissibility]- [CB] We think that there is little doubt that a co-conspirator's statements could themselves be probative of the existence of a conspiracy and the participation of both the defendant and the declarant in the conspiracy. Petitioner's case presents a paradigm. The out-of-court statements of Lonardo indicated that Lonardo was involved in a conspiracy with a "friend." The statements indicated that the friend had agreed with Lonardo to buy a kilogram of cocaine and to distribute it. The statements also revealed that the friend would be at the hotel parking lot, in his car, and would accept the cocaine from Greathouse's car after Greathouse gave Lonardo the keys. Each one of Lonardo's statements may itself be unreliable, but taken as a whole, the entire conversation between Lonardo and Greathouse was corroborated by independent evidence. The friend, who turned out to be petitioner, showed up at the prearranged spot at the prearranged time. He picked up the cocaine, and a significant sum of money was found in his car. On these facts, the trial court concluded, in our view correctly, that the Government had established the existence of a conspiracy and petitioner's participation in it.

- [Statements Alone? [FRE 801(d)(2) Final]]

- [CB] We need not decide in this case whether the courts below could have relied solely upon Lonardo's hearsay statements to determine that a conspiracy had been established by a preponderance of the evidence. To the extent that Glycerinate that courts could not look to the hearsay statements themselves for any purpose, it has clearly been superseded by Rule 104(a). [But the amended language makes it clear that you need more than just the statements]. *** We have no reason to believe that the District Court's factfinding of this point was clearly erroneous. We hold that Lonardo's out-of-court statements were properly admitted against petitioner.

- [CB] [The Court also concludes that the coconspirator exception is "firmly enough rooted in our jurisprudence" so that the Confrontation Clause [6th Am.] does not require an independent inquiry into reliability. Hence receipt of the statements here did not violate defendant's rights under the Confrontation Clause. This part of the decision is considered in Chapter 4G3, infra.]

- The judgment of the Court of Appeals is affirmed.

- [The authors critique the constitutional analysis:]

- The majority has it both ways: The exception is different from what it was, but in its new form it is "firmly rooted" (exempt from a constitutional requirement of showing reliability).

- The Dissent:

- [CB] [The dissent says that the majority is wrong on three points. First, the Federal Rules do not change the requirement that "preliminary questions of fact, relating to admissibility of a nontestifying coconspirator's statement, must be established by evidence independent of that statement." Second, abandoning the independent evidence requirement eliminates "one of the few safeguards of reliability that this exemption from the hearsay definition possesses." Third, the coconspirator exception is not a "firmly rooted hearsay exception" for purposes of the Confrontation Clause.]

- Malavet

- I gave short-shrift to the larger policy arguments, favoring instead a discussion of what the rule actually says. However, the constitutional argument is important because the supremes change or change their minds about such questions, occasionally, which is precisely what happens in Crawford. But, as discussed note 4 following the case, Crawford suggests that the co-conspirator exception is constitutionally safe.

- Notes [CB]

- [CB] 5. Because of the coincidence problem -the coventurer requirement raising both an issue of predicate fact for the coconspirator exception and an ultimate issue in a conspiracy prosecution-some have thought that the jury should be put in charge of applying the coconspirator exception. Under what came to be called the Apollo approach, the question whether the coconspirator exception applies would be treated as an issue of conditional relevancy under FRE 104(b), rather than admissibility under FRE 104(a). The jury would be told to consider a coconspirator statement as evidence against the defendant only if it found that declarant and defendant conspired. United States v. Apollo, 476 F.2d 156 (5th Cir. 1973). The decision in Bourjaily rejects this possibility, does it not? [YES, the jury should NOT be so instructed.]

Problem 4-I: Drugs Across the Border

- Part of the Question, Authors' Answers, with my comments

- (1) testimony by Connie describing what Bud told her in the bar (Arlen "fronted us the buy money"), over Arlen's objection;

- (2) testimony by Don describing what Arlen said (Bud's "gone south to make the buy"), over Bud's objection; and

- (3) testimony by the DEA agent describing what Carol told him ("Bud made the buy"), over Bud's objection.

- Do any or all of these statements fit the coconspirator exception?

- Initially, note that the objecting party is not the declarant, against whom the statements are admissible under FRE 801(d)(2)(A). The objection is to the use of one party's statements against a co-party, since all three of them are charged and tried together. The reason is that FRE 801(d)(2)(E) expressly avoids the Bruton problems.

- [Agency: Admissible Against All]

- The furtherance requirement is an expression of the agency rationale underlying the exception, which in turn is borrowed from the substantive concept of conspiracy. *** In effect, the agency argument says that each conspirator is responsible for the statements of each other conspirator because those statements are admissible against all.

- If we look at Bud's statements in front of Connie as friendly chit chat about a business trip, then it probably does not meet the "furtherance" standard. However, Ms. Miller quite insightfully argued that if we spin it as a statement intended to calm Carol's fears regarding her participation in the conspiracy, then perhaps it would meet the furtherance standard (that was good!).

- Authors: Carol, Bud and Connie: Casual Conversation

- Connie's statement in the bar would likely be termed "mere narrative" because it does not advance the conspiracy. See United States v. Posner, 764 F.2d 1535, 1537-1538 (11th Cir. 1985) (letter to outsider that simply "spilled the beans" on a tax conspiracy could not satisfy furtherance requirement) [I am not sure that Bud and Carol spilled anything, I don't read their statements as indicating that they were importing cocaine, just importing something for which Arlen gave them the money]; United States v. Eubanks, 591 F.2d 513, 520 (9th Cir. 1979) ("casual admission of culpability" to someone whom declarant had decided to trust did not further the conspiracy). The fact that it is uttered in the presence of an outsider (Connie) in casual conversation in a bar both point toward this conclusion.

- Malavet

- It is important to identify the declarant as one of the members of the conspiracy. However, do note that the listener does not have to be a member of the conspiracy. Just that the statement is offered against a party to the conspiracy, was made during the existence of it, and was intended to further the conspiracy. Accordingly, statements to undercover agents or informants are subjectively intended by the declarant to further the conspiracy, but in fact do not (they just get him caught!).

- [DEA Agent Don's Account of Arlen's Statements]

- Don's account of his conversation with Arlen (Bud's "gone south to make the buy") satisfies the furtherance requirement even though the statement destroyed the venture. The furtherance requirement means that the statement seems to further the venture, presumably from the perspective of the declarant, or (more likely) from the perspective of someone in his position acting reasonably (though unaware that his audience is in the enemy camp) with that purpose in mind. See United States v. James, 510 F.2d 546, 548-550 (5th Cir. 1975), cert. denied, 423 U.S. 855 (statements to undercover agent were within exception where declarant "considered her a full-fledged partner in crime").

- [Carol's Post-Arrest Admission]

- (3) Carol's admission to arresting agents (implicating herself and claiming "Bud made the buy") raises the Bruton problem. The statement is obviously admissible against her under FRE 801(d)(2)(A), but its admitting it would violate Bud's confrontation rights under Bruton. See footnote 3 in Bruton, stressing (by citing Krulewitch and Fiswick) that the coconspirator exception does not cover post-arrest confessions by one of several co-offenders.

- [Verbal Act: Conditional Admissibility]

- Sometimes a coconspirator statement is essentially a verbal act that has little or no use as proof of some external fact. On facts like those in Problem 4-H, the statement of drugselling conspirator Arlen that the price of cocaine is "Hundred thou per brick" is this sort of verbal act. In this instance, the question whether Arlen's statement proves anything against Bud and Carol may safely be left to the jury as a question of conditional relevancy under FRE 104(b): The trial judge could invite the jury to consider what Arlen said as evidence against Bud and Carol if it concludes that Bud and Carol were in on the scheme with Arlen, and here the trial judge need not reach a decision on that point herself, except to the extent of deciding whether the evidence suffices to establish the point.

- Malavet

- I find the arguments about verbal act deeply troubling in the context of a conspiracy prosecution. If any case calls for the statement to be treated as such for hearsay purposes it is one made in furtherance of the conspiracy. Accordingly, I would prefer that you find that this is indeed a statement being offered to prove the truth of the matter asserted under FRE 801(a),(b),(c) and then try to resolve the 801(d)(2)(E) elements.

- [Procedure: Timing]

- The judge is likely to admit Arlen's statement to Don whenever the prosecutor finds it convenient, subject to a motion to strike if the prosecutor fails to adduce independent evidence of the conspiracy. He is likely to make a preliminary finding that there is prima facie evidence of conspiracy (perhaps on the basis of a James hearing in which agents testify to the observed movements of the three defendants, perhaps simply on the basis of the prosecutor's assurance that evidence of that behavior will be adduced).

- Malavet

- I suppose that a proffer by the prosecution , rather than an extensive hearing might be allowed. It is an efficient result (you only hear the evidence once, which makes sense in a strong case); but this is dangerous, if the prosecutor fails to prove the conspiracy striking the evidence will be a very poor remedy, mistrial might be more appropriate.

- [Procedure: The entire picture?]

- If asked by the defense, the judge will likely make a final decision under FRE 104(a) that Arlen, Bud, and Carol did indeed conspire in the drug business, and that Arlen's statement satisfies the pendency and furtherance requirements. Again, the judge will base his decision on the "independent evidence" of the behavior of the three during the time, and will conclude that this evidence establishes the predicate facts by a preponderance of the evidence.

- Malavet

- I have no doubt that this should occur without the jury being present. FRE 104(c).

4.07 Hearsay: Unrestricted Exceptions

FRE 803(1) Present Sense Impressions

- The following are not excluded by the rule against hearsay, regardless of whether the declarant is available as a witness:

- (1) Present Sense Impression.

- [a] A statement describing or explaining an event or condition,

- [b] made while or immediately after the declarant perceived it.

- The following are not excluded by the rule against hearsay, regardless of whether the declarant is available as a witness:

- (2) Excited Utterance.

- [a] A statement relating to a startling event or condition,

- [b] made while the declarant was under the stress of excitement that it caused.

Case: Nuttall v. Reading Co.

- [CB: The offered Evidence]

- In the second trial, the court directed a verdict against Florence Nuttall, from which she took this appeal. Here she urged error in the exclusion of evidence, including

- (1) two affidavits (one by Fireman John O'Hara, the other by Conductor James Snyder, both of whom worked with Nuttall on the occasion in question),

- (2) her own testimonial account of her husband's phone conversation with the yardmaster, and

- (3) testimony by the fireman about remarks Nuttall made in the trainyard on the day in question.

- In the second trial, the court directed a verdict against Florence Nuttall, from which she took this appeal. Here she urged error in the exclusion of evidence, including

- [CB: Legal Standard]

- If the plaintiff in this case can prove that management forced a sick employee, of whose illness they knew or should have known, into work for which he was unfitted because of his condition, a case is made out for the jury under the Federal Employers' Liability Act. As to this general proposition we think there is no dispute....

- [Wife's Testimony Regarding the Telephone Conversation]

- [CB] Now we turn to the other vital piece of testimony. On the morning of January 5, 1952, Nuttall had a telephone conversation from his home with the yardmaster at Wilmington. This conversation took place in the presence of his wife and at the end there was an additional statement made to her after he had hung up the receiver. Here is the conversation which plaintiff offered and the district judge refused . . .:

- Q. Suppose you start again. He got on the phone and he dialed the office and he said something to George.

A. Yes. He said, "George," he said, "I am very sick, I don't think I will be able to come to work today."

Q. What was the next you heard your husband say?

A. I heard him say, "But I can't come to work today, I don't feel I can make

Q. What was the next thing you heard your husband say?

A. I heard him say, "but, George, why are you forcing me to come to work the way I feel?"

Q. Then did your husband say anything after that?

A. Well, he said, "I guess I will have to come out then."

Q. Was that the end of this conversation on the telephone?

A. It was.

Q. Then what did he do with the telephone?

A. He put the telephone back.

Q. Then did you help him? Then what happened? Did he go off, or go to work, or did he remain in the house, or what?

A. No, he went to work, he said to me, "I guess I will have to go."

- Q. Suppose you start again. He got on the phone and he dialed the office and he said something to George.

- [CB] Now we turn to the other vital piece of testimony. On the morning of January 5, 1952, Nuttall had a telephone conversation from his home with the yardmaster at Wilmington. This conversation took place in the presence of his wife and at the end there was an additional statement made to her after he had hung up the receiver. Here is the conversation which plaintiff offered and the district judge refused . . .:

- [CB] Is the telephone conversation evidence of pressure by the employer? ***

- [CB] We think that the conversation tends to show that Nuttall was being forced to do something by somebody. The "somebody" is identified without difficulty. He was Marquette the railroad employee in charge of operations in the yard. Knowing that Nuttall's superior was talking to him on the telephone we think that the words Nuttall used during the time and his statement immediately afterward tend to show that he was being forced to go to work. At this point we are assuming Nuttall's state of mind established and seeking probative evidence that his state of mind was induced by something his employer did. When a man talks as Nuttall did and acts as Nuttall did during and immediately following a conversation on the telephone with his boss, it has a tendency to show that the boss was requiring him to come to work against his will.

- [CB] *** [Reliable?]

- She did hear her husband characterize the statements of his boss at the very moment he heard what Marquette had to say and immediately thereafter. Such characterizations, since made substantially at the time the event they described was perceived, are free from the possibility of lapse of memory on the part of the declarant. And this contemporaneousness lessens the likelihood of conscious misrepresentation. All things considered, we think that Nuttall's statements during and immediately following the telephone conversation should be admitted into evidence to prove that he was being compelled to come to work.

- Malavet

- To put it most simply, as explained in note 3 after the case, FRE 803(1)'s reference to "perceived" includes events, acts and words. Therefore, Nuttall's statements about what he heard are admissible to prove what Marquette said, which is proof that the company forced Nuttall to go into work. Harmless? NOT!

- [CB] Mistakes on admissibility of evidence are almost inevitable during a hotly contested trial. Unless they seriously affect the case they are not a ground for reversal. But here the rejected evidence goes to the very heart of the plaintiffs case. It is unfortunate that this type of case must be tried three times. But that is necessary in this instance.

- Notes:

- [Please pay special attention to the specific examples in the notes.]

4.08 Hearsay: Unrestricted Exceptions: Excited Utterances

Case: U.S. v. Arnold

- [CB] United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit 486 F.3d 177 (2007).

- [CB] Under FRE 803(2), a court may admit out-of-court statements for the truth of the matter asserted when they "relat[e] to a startling event or condition made while the declarant was under the stress of excitement caused by the event or condition." To satisfy the exception, a party must show three things. "First, there must be an event startling enough to cause nervous excitement. Second, the statement must be made before there is time to contrive or misrepresent. And, third, the statement must be made while the person is under the stress of the excitement caused by the event." Haggins v. Warden, Fort Pillow State Farm, 715 F.2d 1050, 1057 (6th Cir. 1983). All three inquiries bear on "the ultimate question": "[W]hether the statement was the result of reflective thought or whether it was a spontaneous reaction to the exciting event." Id. at 1058 (internal quotation marks omitted). We apply abuse-of-discretion review to a district court's application of the rule.

- [CB] Contrary to Arnold's suggestion, our cases do not demand a precise showing of the lapse of time between the startling event and the out-of-court statement. The exception maybe based solely on "[t]estimonythat the declarant still appeared nervous or distraught and that there was a reasonable basis for continuing [to be] emotional[ly] upset," Haggins, a conclusion that eliminates an unyielding requirement of a time line showing precisely when the threatening event occurred or precisely how much time there was for contrivance. The district court made this exact finding, a finding supported by evidence that, in the words of Haggins, "will often suffice."

- [CB] Case law supports the view that Gordon made the statement "before there [was] time to contrive or misrepresent." [HOW?]

- [CB] The dissent, though not Arnold, raises the concern that the uncorroborated content of an excited utterance should not be permitted by itself to establish the startling nature of an event. But this issue need not detain us because considerable nonhearsay evidence corroborated the anxiety-inducing nature of this event: [NOTE THE FACTORS]

- [CB] The dissent's view of the excited-utterance question prompts a few responses. First, the dissent, though not Arnold, contends that the district court failed to place the burden of proof on the government. Yet the district court, in making this ruling, concluded that "the elements to allow the exception have been demonstrated by the government." And we, too, have placed the burden on the government.

- [CB] Second, the dissent claims that, instead of saying "he's fixing to shoot me," Gordon said "he finna shoot me," thereby eliminating the '''s'' between he and finna (which the dissent finds to be a slang term for "fixing to"). But Arnold has not challenged the district court's factual determination that Gordon told the 911 operator "he's fixing to shoot me," and accordingly this issue is not properly before us. Nor, at any rate, is it clearly the case, or even somewhat clearly the case, that the dissent properly interprets the tape-given the rapidity and anxiety with which Gordon spoke during the 911 call. This difficulty reinforces not only our decision to defer to the district court's interpretation of the tape but also our decision that indeed it was an excited utterance.

- [What about Crawford? Read the short editorial note on this.

- [All of these statements fit the emergency exception that allows use of testimonial statements under Crawford.]

- [Excerpts from the majority's discussion of "Testimonial vs. Emergency":]

- As Davis 's assessment of the 911 call and the on-the-scene statements indicates, the line between testimonial and nontestimonial statements will not always be clear. Even if bona fide 911 calls frequently will contain at least some nontestimonial statements (assuming the emergency is real and the threat ongoing) and even if a victim's statements to police at the scene of the crime frequently will contain testimonial statements (assuming the emergency has dissipated), that will not always be the case, and difficult boundary disputes will continue to emerge. Each victim statement thus must be assessed on its own terms and in its own context to determine on which side of the line it falls.

- ***

- 911 call. ...

- In Davis, the assailant left the scene in a car because he knew the police were on their way, and there thus was no reason to think that he would be back-factors that markedly diminished the peril the victim faced. Gordon by contrast left the residence, went around the corner and called the police. At the time she made the call, she had no reason to know whether Arnold had stayed in the residence or was following her. What she did know is that he had a gun; he had just threatened her; he was still in the vicinity; there was still "somebody runnin' around with a gun" nearby, United States v. Thomas, 453 F.3d 838, 844 (7th Cir. 2006) (internal quotation marks omitted); there was in short an "emergency in progress," Davis, 126 S. Ct. at 2278.

- Nor need we consider whether the 911 call evolved into testimonial hearsay over the course of its nearly two-minute duration. Arnold makes no such argument; he contends only that the entire call should have been suppressed because the exigency had dissipated before the call began.

- Gordon's statement to officers upon their arrival at the crime scene.

- While it may often be the case that on-the-scene statements in response to officers' questions will be testimonial because the presence of the officers will alleviate the emergency, this is not one of those cases. Neither the brief interval of time after the 911 call nor the arrival of the officers ended the emergency. Arnold remained at large; he did not know that Gordon had called 911; and for all Gordon (or the officers) knew Arnold remained armed and in the residence immediately in front of them or at least in the nearby vicinity.

- The exchange between Gordon and the officers also suggests that the officers primarily were focused on meeting the emergency at hand, not on preparing a case for trial. As soon as the police arrived and before they had a chance to ask her a question, Gordon exited her car, "walked towards [them], . . . crying and . . . screaming, [and] said Joseph Arnold pulled a gun on her, [and] said he was going to kill her." JA 114. The officers tried to "tell[] her to gather herself and [to] slow down." JA 115.

- While the fact that Gordon's initial statement was unprompted and thus not in response to police interrogation does not by itself answer the inquiry, Davis, 126 S. Ct. at 2274 n.1, this reality at least suggests that the statement was nontestimonial. So, too, does the distress that the officers described in her voice, the present tense of the emergency, the officers' efforts to calm her and the targeted questioning of the officers as to the nature of the threat, all of which suggested that the engagement had not reached the stage of a retrospective inquiry into an emergency gone by. No reasonable officer could arrive at a scene while the victim was still "screaming" and "crying" about a recent threat to her life by an individual who had a gun and who was likely still in the vicinity without perceiving that an emergency still existed. And nothing that Gordon told them, and certainly nothing about the way she told it to them, would have allayed concerns of a continuing threat to Gordon and the public safety, to say nothing of officer safety.

- During the few moments the officers spoke to Gordon, moreover, the primary purpose, measured objectively, of the question they asked her -- for "a description of the gun," JA 133 -- was to avert the crisis at hand, not to develop a backward-looking record of the crime. Contrary to the contention of the partial dissent, this question did not transform the encounter into a testimonial interrogation. Asking the victim to describe the gun represented one way of exploring the authenticity of her claim, one way in other words of determining whether the emergency was real. And having learned who the suspect was and having learned that he was armed, they surely were permitted to determine what kind of weapon he was carrying and whether it was loaded -- information that has more to do with preempting the commission of future crimes than with worrying about the prosecution of completed ones. What officers would not want this information -- either to measure the threat to the public or to measure the threat to themselves? Cf. Davis, 126 S. Ct. at 2276 (911 operator's questions regarding assailant's identity objectively aimed at addressing emergency because "the dispatched officers might" then "know whether they would be encountering a violent felon"). And what officer under these circumstances would have yielded to the prosecutor's concern of building a case for trial rather than to law enforcement's first and most pressing impulse of protecting the individual from danger? ***

- DISSENT:

- Malavet

- I am not unsympathetic to the dissent, but the majority disposes of this by noting that the defendant failed to make it an issue and that they would therefore defer to the district court's factfinding. Let it be a lesson as to what to argue.

- [CB] Next, the majority places undue emphasis on its interpretation of the tape. Although I question the utility of semantically dissecting Gordon's statements, even if I take the majority's approach, the tape does not indicate that Gordon spoke to the 911 operator before sufficient time to contrive or misrepresent had passed. According to the majority, Gordon said, "he's fixing to shoot me," as opposed to "he was fixing to shoot me." After listening to the tape multiple times, I hear the words: "I guess he finna shoot me." I find this significant for two reasons. First, Gordon's inclusion of the words "I guess" (which the majority cleverly excises) renders her statement far less definitive than the majority chooses to present it. More importantly, the statement contains no auxiliary verb (e.g., "is" or "was") connected to "finna," which I understand to be a slang contraction for "fixing to," much as "gonna" serves as a contraction for "going to." See, e.g., http://www.urbandictionary.com/define.php?term= finna (last visited Apr. 19, 2007) (defining "finna" as, "Abbreviation of 'fixing to.' Normally means 'going to.' ,,).8 ...

- Malavet

- [CB, footnote]

- 8. Understanding Gordon's statements in the 911 tape requires an understanding of slang, which is constantly evolving. Turning to a source that operates by consensus, and thus develops along with slang usage, therefore seems unusually appropriate in this instance. Urban Dictionary. com is such a source, as it permits users to propose definitions for slang terms, and other users to vote on whether they agree with the particular definitions posited. At the time of the last visit, the definition cited above (which was posted in June 2003) had received 272 positive votes, and only 45 negative votes, making it the most popular of the twenty proposed definitions of "finna," all but one of which connote future action.

OLD Case: U.S. v. Iron Shell

The fact of assault and identity of the assailant are conceded; the question is whether John Louis Iron Shell intended to commit rape.

- [CB] Defendant, John Louis Iron Shell, appeals from a jury conviction of assault with intent to commit rape in violation of the Major Crimes Act, 18 U.S.C. §1153 (1970). Iron Shell raises ten issues on appeal. The . . . primary questions [include] two evidentiary rulings concerning hearsay.... We affirm the jury conviction.

- [The Assault]

- [CB] At about this point Pam Lunderman arrived. She testified that she saw Lucy come out of the bushes pulling up her pants and crying. Lucy told Lunderman, "that guy tried to take my pants off." Lunderman testified that Lucy had weeds on her back and head, that her hair was disheveled and that her face was swollen on one side. Both Steve and Mike saw Lucy come out of the bushes and confirmed Lunderman's testimony. Mike told the jury that Lucy was "crying hard," looked scared and that her jeans were down to her knees. Steve said he saw Lucy coming out of the bushes pulling up her pants and that she was crying. The time of the assault is uncertain, but it was somewhere between 6:00 and 6:30 P.M.

- [Officer Marshall]

- [CB] Meanwhile, Officer Marshall conducted an interview with Lucy which began at about 7:15 P.M. in the magistrate's home and ended at about 7:30 P.M. Officer Marshall, according to her testimony, asked Lucy a single question: "What happened?" In response Lucy related the following. Lucy said her assailant grabbed her and held her around the neck and told her to be quiet or he would choke her. He told her to take her pants down and when she refused, he pulled them partially off. Lucy told Officer Marshall, "he tried to[,] what you call it[?,] me."4 Lucy also said that he had his hands between her legs. Officer Marshall recounted Lucy's statement in full at trial.5

- [CB] Officer Marshall also testified that Lucy was not hysterical nor was she crying, but that her hair was messed and had leaves in it, that she appeared nervous and scared, and that her eyes were red....

- [Lucy's later statements to Dr. Hopkins, who examined Lucy at about 8:20P.M., fit the medical statements exception in FRE 803(4) and were properly admitted.]

- AUTHORS:

- (In omitted segments of the opinion, the court adds that Lucy testified that Iron Shell "hit her on the side of the face" and "held her down," and she told the doctor he "tried to force something into her vagina which hurt.")

- [The grounds for objection. I thought of editing this out, but the objection is well-explained.]

- [CB] The defendant . . . asserts that it was prejudicial error to admit the hearsay testimony of Officer Marshall pursuant to 803(2). The rule allows admission of hearsay, otherwise competent, that is a "statement relating to a startling event or condition made while the declarant was under the stress of excitement caused by the event or condition." FRE 803(2). Officer Marshall interviewed Lucy at 7:15 P.M.; somewhere between forty-five minutes and one hour, fifteen minutes after the assault. The defense argues that Lucy was no longer "under the stress of excitement caused by the event" when she talked to Officer Marshall. The defendant emphasizes that Lucy was described as quiet and not crying, and that she had not made any spontaneous statements since immediately following the assault. He also asserts that Lucy's statements were not spontaneous because they were in response to an inquiry and were the product of reasoned reflection fostered by conversations between herself and her companions following the assault. The government, in response, stresses that Officer Marshall described Lucy as scared and nervous with her eyes still red from crying and her hair was still messed from the assault.

- [Factors]

- [CB] The

- [1] lapse of time between the startling event and the out-of-court statement although relevant is not dispositive in the application of rule 803(2)....

- [2] Nor is it controlling that Lucy's statement was made in response to an inquiry.... Rather, these are factors which the trial court must weigh in determining whether the offered testimony is within the 803(2) exception. Other factors to consider include

- [3] the age of the declarant,

- [4] the physical and mental condition of the declarant,

- [5] the characteristics of the event and

- [6] the subject matter of the statements.

- [Required Finding:][CB, end of the paragraph] In order to find that 803(2) applies, it must appear that the declarant's condition at the time was such that the statement was spontaneous, excited or impulsive rather than the product of reflection and deliberation.

- [CB] Abuse of Discretion/Totality of the Circumstances]

- Applying this standard, we cannot say that the district court abused its discretion. The single question "what happened" has been held not to destroy the excitement necessary to qualify under this exception to the hearsay rule. A lapse of about one hour has also been held not to remove the evidence from the 803(2) exception, especially where the declarant is a young child. It also has been noted that the lack of recall may indicate that the declarant was under stress at the time of the statement. It is a truism to state that each of these cases must be decided on its own circumstances. We find that in these circumstances considering the surprise of the assault, its shocking nature and the age of the declarant, it was not an abuse of discretion for the trial court to find that Lucy was still under the stress of the attack when she spoke to Officer Marshall. It was not unreasonable, in this case, to find that Lucy was in a state of continuous excitement from the time of the assault.

- [Harmless Error]

- [CB] Even if Officer Marshall's testimony concerning Lucy's statement was found to be inadmissible hearsay under 803(2), it is our view that the evidence was at most cumulative and therefore constituted harmless error.... In this case the defense presented no evidence to contradict the officer's testimony while it was supported, at least partially, by three other witnesses.

- [Confrontation Clause, 6th Am.]

- [CB] At trial Lucy was unable to repeat the statements she had made to Officer Marshall and Dr. Hopkins although she was able to provide some facts to support her earlier statements. Defense counsel crossexamined Lucy but did not ask about the assault or her statements shortly thereafter. It is difficult to conclude on this record that a more thorough cross-examination would not have provided the protections inherent in the confrontation clause. Nevertheless, assuming arguendo that Lucy was unavailable..., we conclude that the confrontation clause was not violated because the admitted hearsay statements, particularly those given to Dr. Hopkins, had sufficient indicia of reliability in order to afford the trier of fact a satisfactory basis for evaluating the truth of the prior statements.

- Malavet

- Keep in mind that ours is an evidence course, not one on Constitutional Criminal Procedure. Therefore, neither I nor your casebook authors go out of our way to focus on the Constitutional provisions. Nevertheless, do not allow that to suggest that the constitutional provisions are in any way less important than the rules of evidence.

- Notes

- [CB] 3. What if the time lapse had been 12 hours instead of 45 to 75 minutes? Compare People v. Smith,581 N.W. 2d 654, 668 (Mich. 1998) (admitting statement by 16-year-old male describing sexual assault approximately nine hours earlier; speaker's behavior between assault and statement was extraordinary, revealing "continuing level of stress arising from the assault that precluded any possibility of reflection") and State v. Stafford, 23 N.W.2d 832, 835 (Iowa 1946) (admitting statement by farm wife who spent the night wandering in the fields, naming her husband as her assailant, although she was speaking some 14 hours after the event) with United States v. Marrowbone, 211 F.3d 452, 454-456 (8th Cir. 2000) (error to admit statements by 16-year-old victim of sexual assault describing the crime, where these were made three hours after the event "by a teenager, not a small child," and "teenagers have an acute ability to fabricate") (harmless).

- [Note that the declarant's experience with stress is also relevant.]

Problem 4-J: I felt this sudden pain:

Authors' Answers, with my comments and questions

- [The statement]

- "I felt this sudden pain just a few minutes ago when I had to lift one of those 30-gallon cans out on the Chase."

- Malavet

- Note that the event that the statement is being used to prove is on the job injury, rather than the heart-attack itself. After class, one student characterized the heart attack as an ongoing event, I think quite accurately. But, the widow was attempting to prove not the heart attack, but its onset as a result of on the job lifting, so I would define "the event" narrowly in this context to mean the onset of the on-the-job injury, and the feeling of pain that occurred at the moment of lifting.

- On a substantive question, I assume that applicable law allows recovery for on-the-job injury such as a heart attack. If that is so, then the onset of the heart attack as a result of job-related stress would prove plaintiff's case (hence the relevance of the statement). The counter-argument that causation is not proved (the heart attack might have been caused by bad eating habits), is countered in two possible ways: (1) all the substantive law requires is that the attack occur while at work, or (2) even if there was a causation question, the statement is still relevant to suggest on-the-job causation, subject to countering; but it would be relevant and admissible nonetheless, although its weight is a different question.

- [Bootstrapping Problem: The statement provides its own (and, arguably, only) foundation

[FRE 803(2)] [Compare FRE 803(1)]- Can a statement admitted as an excited utterance prove the happening of the event on which its own admissibility depends? If so, we have again the circularity or bootstrapping problem. Theoretically, requiring independent evidence makes sense for the same reason that it did before: The exception should be applied in a reasonable way, and letting a statement prove its own predicate facts comes close to admitting statements that speak of exciting events rather than excited statements. Even Bourjaily stops short of saying a coconspirator statement alone can prove its own predicate.

- (While the ACN amended FRE 801(d)(2) after Bourjaily, adopting the view that statements offered as authorized admissions, statements by agents, or coconspirator statements could themselves be considered as at least partial proof of the predicate facts, there has been no move to amend FRE 803(2) in similar fashion.) [Compare FRE 803(1)]

- [The Better Rule: Admit it: Objection Overruled]

- Still it seems wrong to impose this requirement here. As always, we can say FRE 104(a) frees the judge (in determining admissibility) from the constraints of evidence rules. And we have compelling legislative support -- the ACN endorses rulings admitting statements where "the only evidence" of a startling event is "the content of the statement itself."

- We think this outcome is right for two reasons:

First, denying recovery in possibly deserving cases where a job situation makes firsthand evidence scarce is simply intolerable.

Second, courts have applied the requirement badly. Usually we have independent proof of an exciting event -- clinical evidence of ailment or injury, or lay observations of the speaker acting "out of sorts."

- [Independent Evidence]

- On the facts of the problem, there is another kind of independent evidence -- Eldon Sanders came home at midmorning, which he "never" does, and that suggests something unusual happened. Even on these facts (where independent evidence is kept thin), there is more than enough to support a finding that he was affected by an exciting event: In addition to coming home early, Sanders said he was in pain (a statement admissible under FRE 803(3) regardless whether he experienced an exciting event, as students will soon learn), suffered elevated blood pressure, had clinical symptoms of fatigue that led Dr. Hillier to prescribe bed rest for observation, and suffered a fatal heart attack later, which tends to confirm what he said (if he died later of a heart attack, it is likely that he felt symptoms earlier).

- If independent evidence is required, the purpose should not be to demand corroboration of every point asserted in the statement. What we can glean from independent evidence here stops short of showing that Sanders was "out there" when he felt the pain, or even that there was anything "sudden" about it. But a gradual onset of pain can be startling as the victim realizes it isn't "going away by itself," so there is plenty of evidence that Sanders experienced an exciting event. That should be enough to qualify the statement, which can then prove that the exciting event began at work.

- [The Actual Case: Texas would exclude, Minnesota would not.]

-

The problem resembles Travelers Ins. Co. v. Smith, 448 S.W.2d 541 (Tex. Civ. App. 1969), and the Texas cases seem determined to deny workers' compensation recovery in this situation, but cases from other states point toward what we consider the better result. The reason for generosity in this context was put this way in a Minnesota opinion:

- In the larger cities of this state there are many policemen walking their beats alone, day and night. In every small city and hamlet there is a policeman working alone at night. Night watchmen work alone. Other employees work alone. These employees are subject to numerous possibilities of accidents which may cause conditions that may bring about their death. They do not have a witness with them to furnish proof as to the happening of an accident if the injuries they receive close their lips in death. The number of compensation cases which reach the courts of last resort where the only proof of the accident is the declaration of the injured employee give weighty proof of the truth of the declaration of the Pennsylvania court that to give a strict application of the res gestae rule in compensation cases would defeat the intent of the Workmen's Compensation Law. Jacobs v. Buhl, 199 Minn. 572, 273 N.E. 245 (1937).

-

The problem resembles Travelers Ins. Co. v. Smith, 448 S.W.2d 541 (Tex. Civ. App. 1969), and the Texas cases seem determined to deny workers' compensation recovery in this situation, but cases from other states point toward what we consider the better result. The reason for generosity in this context was put this way in a Minnesota opinion:

- Notes:

- [Evil exam question in note no. 2.]

4.09 Hearsay: State of Mind, FRE 803(3)

- FRE 803(3) Then existing mental, emotional, or physical condition.

- The following are not excluded by the rule against hearsay, regardless of whether the declarant is available as a witness:

- (3) Then-Existing Mental, Emotional, or Physical Condition.

- [a] A statement of the declarant’s then-existing state of mind (such as motive, intent, or plan) or emotional, sensory, or physical condition (such as mental feeling, pain, or bodily health),

- [b] but not including a statement of memory or belief to prove the fact remembered or believed unless it relates to the validity or terms of the declarant’s will.

This area is maddening for at least three obvious reasons:

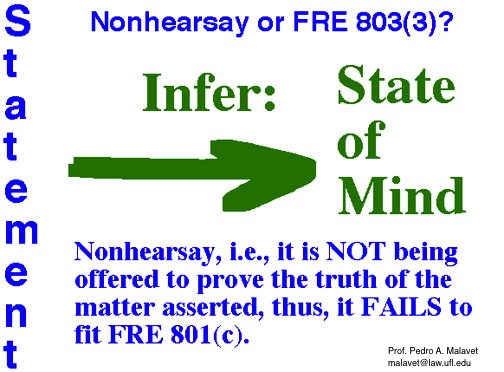

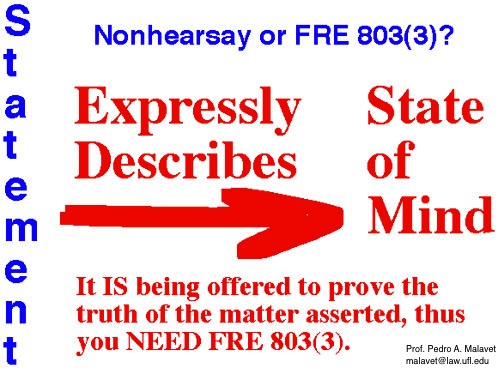

(1) The coexistence of FRE 803(3) with the Non-Truth-ergo-nonhearsay use of statements from which we can infer state of mind [go to Chapter 3 notes].

The inferences fit within at least two of the six "Non-Truth" uses that we covered in Chapter 3: (5) Circumstantial Evidence of State Of Mind, associated with Problem 3-H, and (6) Circumstantial Evidence of Memory or Belief, associated with Problem 3-I.

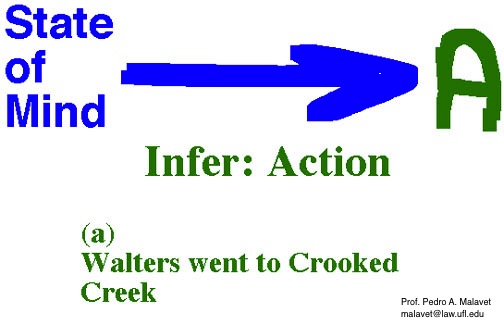

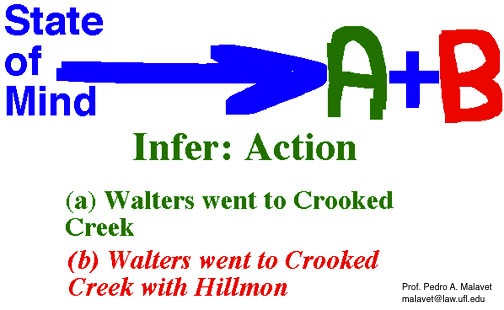

(2) The use of the term "inference" in: (a) The use of statements that prove state of mind to infer action in conformity therewith, vs. (b) the use of statements that assert one thing, but from which we can infer state of mind (e.g. the problems cited above, and Problem 4-J).

(3) The Hillmon doctrine then takes the exception to a possibly absurd extreme.

I can provide you with a reasonable level of comfort on the 803(3) vs. it fails the 801(c) test, and on the inference issue, but I am afraid that Hillmon is a more difficult challenge.

Casebook

- [CB] *** As formulated in FRE 803(3), the exception has four distinct uses: To prove

- (a) declarant's then-existing physical condition,

- (b) his then-existing mental or emotional condition,

- (c) his later conduct, and

- (d) facts about his will.

- [CB] But risks of candor and ambiguity remain, and some cases hold that the exception is unavailable where circumstances suggest insincerity, a risk that may seem considerable in the case of blame-avoiding statements. See United States v. Ponticelli, 622 F.2d 985, 991-992 (9th Cir.) (defendant had time enough "to concoct an explanation"), cert. denied, 449 U.S. 1016 (1980); Fla. Stat. Ann. §90.803(3)(b)(2) (1979) (authorizing exclusion where circumstances indicate "lack of trustworthiness"). But see United States v. DiMaria, 727 F.2d 265, 271-272 (2d Cir. 1984) ("truth or falsity was for the jury to determine," and statement within categorical exceptions "is admissible without any preliminary finding of probative credibility by the trial judge"). Judge for yourself as you proceed whether the exception should be subject to some general power in the trial judge to exclude on account of doubts over veracity of the declarant.

- Malavet

- Note that the Florida statute quite expressly imposes the credibility requirement for admissibility, whereas in the federal system some circuits find it implicit in the rule and some do not.

b. Then-Existing Mental or Emotional Condition

Evidential Hypothesis in General:

The statement (a) Infers or (b) asserts mental or emotional condition, AND that condition is itself an ultimate issue in the case.

- [CB] Fact-Laden Statements]

- This application of the exception is complicated by the fact that often utterances indicating mental state are wholly or partially factual in nature. In what we can call "fact-laden statements," people may purposefully disclose state of mind by speaking in factual terms, choosing to communicate inclinations in that oblique way. Sometimes their main purpose is to communicate facts, but in doing so they also reveal something about inclinations, often consciously, but perhaps subconsciously or unconsciously.

- Malavet

- Fact-laden statements are one illustration of the usual problem in this area: even if probative of state of mind, the entire statement usually includes some objectionable material or may be used by the jury for an impermissible purpose, which raises substantial 403 concerns.

Problem 4-K: He says he'll kill me:

Authors' Answers, with my comments and questions

- [Consider the Statement:]

- Neff is after me again. He says he'll kill me and my family if I don't pay protection. I've already paid him $5,000, and I'm trying to steer clear of him, and I need help but I just don't know what to do.

- Malavet

- In my view, we can INFER Quade's state of mind from the statement, but the statement itself does not assert what Quade felt, which means that this does NOT fall under FRE 803(3), but is rather a non-truth-ergo-nonhearsay use.

- ALTERNATELY, we might read it as necessarily implying fear (trying to steer clear of him, I need help), which would mean that we ARE offering it to prove the assertion ("I am afraid of Neff, because he threatened me"), which would then fall under FRE 803(3).

- I am inclined to go with the inference reading. If the statement were simply "Neff says he is going to kill me if I don't pay protection" the only interpretation of that one is that it INFERS fear, but does not assert it.

- [403 Balance]

- Where a statement tends to prove both a relevant state of mind and damaging facts, the real question is whether the risk of unfair prejudice outweighs probative worth.

- [Prejudice]

- "Prejudice" here means misuse of Quade's statements as proof of what Neff said, and the risk seems about the same, whether the charge is extortion or murder.

- [Legitimate Probative Worth: Extortion: Legitimate to show fear on the part of the victim]

- But probative worth is greater in the extortion case (fear being an element of the crime), and the words of the victim are just about the best imaginable evidence.

- In extortion trials, many cases approve use of statements of fear by the victim [from which we might infer] or openly asserting that defendant made threats, as illustrated by the Collins case (note 1 after the problem).

- [Probative Worth: Murder]