Evidence Notes File 1

LAW 6330 (4 credits)

Professor Pedro A. Malavet

I. Evidence Law and the System

- “The Forest:” I will use this heading to include brief notes describing the fundamental concepts that you should get out of each chapter.

- The Forest in Chapter I: This introductory chapter is an overview of the context, the mechanics, and most importantly, the language of Evidence. While we may not discuss each term in class, you must familiarize yourself with the vocabulary of evidence that will be used for our discussion in the future.

I.A. Introduction [Session 1]: Why Evidence? and What Happens at The Trial

- Introductorily, I will expect you to read and to understand the rules set forth in the General Information section of the Syllabus. Please review them with care.

- Recommended movie scenes for today come from "... And Justice for All", a 1979 release by Columbia Pictures. The movie is available at the Legal Information Center. I recommend "the opening statement" and "Gentlemen ... need I remind you that you are in a court of law."

Why Evidence, Five Reasons:

- (1) Mistrust of Juries [FRE 403]

- (2) Substantive Policies Related to the Case [Burdens of Proof and Persuasion] [FRE 302]

- (3) Substantive Policies Not Related to a Specific Case [FRE 501]

- (4) Accuracy in Fact-finding [Rule 611]

- (5) Efficiency and Reasonableness [FRE 102]

[1] A second reason for the law of evidence is to serve substantive policies relating to the matter being litigated.

[1] A third reason is to further substantive policies unrelated to the matter in litigation-what we may call extrinsic substantive policies.

[2] A fourth reason for the law of evidence is to ensure accurate fact finding.

[2] The fifth reason for evidence law is pragmatic-to control the scope and duration of trials, because they must run their course with reasonable dispatch.

[2] They apply in federal courts across the land in both criminal and civil cases, and generally they apply regardless whether federal or state law supplies the rule of decision. (In diversity cases where federal courts apply state substantive law, however, the Rules require federal courts to apply state evidence rules in limited areas -namely, presumptions, competency of witnesses, and privileges. See FRE 301, 501, and 601.)

I recommend that you download or copy the Florida Evidence Code (Florida Statutes 90.101 et seq.) and compare them to the Federal Rules. You will note that the Florida Code is structured to mirror the Federal Rules, but that it has important additional coverage, especially in the area of privileges.

Stages of the Civil Case

- -Prior to filing: Controversy/ Reasonable Investigation. R. 11.

- -After Filing:

- 1. Complaint

2. Answer

3. Intervention Motion

4. Counterclaim

5. Answer to the counterclaim

6. Amended Complaint

7. Answer to Amended Complaint.

8. Discovery? (Discovery Plan & Scheduling Order)

9. Final Pretrial Order

10. Motion for Recusal

11. Trial

12. Second Amended Answer

13. Mistrial Motions

14. Judgment

15. Appeal

- 1. Complaint

Stages of the Criminal Case

- -Occurrence of an alleged crime

- -Reporting of the alleged crime

- 1. Arrest/Citation

2. Presentment/Conditions of Release

3. Indictment or Information

4. Preliminary Hearing

5. Arraignment

6. Preliminary Process:

Pretrial motions and discovery

7. Trial

8. Judgment

9. Post-Trial Motions/New Trial

10. Appeal

11. Collateral Attacks on judgment

- 1. Arrest/Citation

We discussed the stages of trial, which is the assumed context for the application of the federal rules of evidence. The book gives you ten (10) to which I would add an eleventh: collateral attacks after appeals are exhausted, especially in criminal cases.

What Happens at Trial:

- 1. Jury Selection

2. Opening Statement

3. Presentation of Proof

4. Trial Motions

5. Closing Arguments

6. Instructions

7. Deliberations

8. The Verdict

9. Judgment and Post-Trial Motions

10. Appellate Review (Preserved Issues)

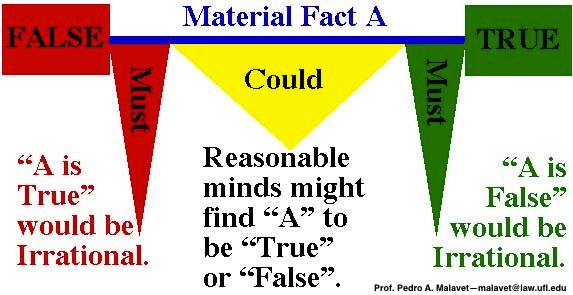

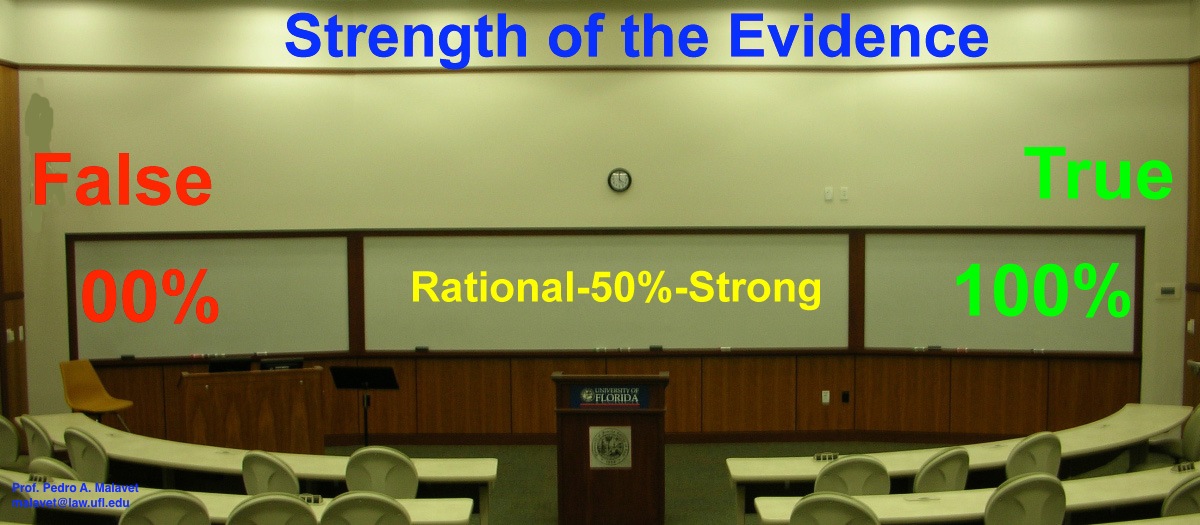

Another graphic presentation that I use in class:

Proof at Trial: Notes

- Ultimate Issue(s) I:

-> Criminal: Guilt or No Guilt

-> Civil: Liable or Not, Damages or Not, Equitable Remedies or Not - Ultimate Issue(s) II:

Definition:

Legal Facts

Criminal:

Mens Rea, Actus Reus, Attendant Circumstances, Defenses

Civil: E.g.,

Negligence, Proximate Cause, Breach of Contract, Damages - Facts of Consequence:

Definition:

Through inference, or directly, prove or disprove ultimate issues.

Criminal:

Defendant spent days planning the crime,

Defendant shot victim in the heart

Civil:

Defendant failed to stop at red light,

Defendant failed to pay for services rendered - Subsidiary Facts:

Definition:

Through inference, prove or disprove

(1) facts of consequence; or (2) ultimate issues.

Criminal:

Bullet hole through heart,

fingerprints on gun, receipt for ski mask.

Civil:

Defendant said, "Oh no; the light, it wasn't green," at the scene of auto accident;

stop-payment order found in bank records.

Civil or Criminal:

defendant said, "it's all my fault."

The Mechanics of Trial

- Evidence is presented at trial in parts, and in the following general order, subject to change under certain rules, such as FRE 106 and FRE 611(b)[2].

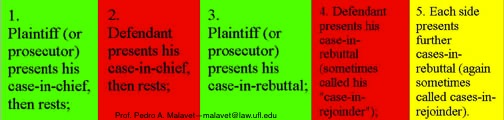

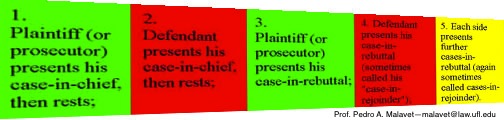

- [CB] To sum it up, the order of proof goes this way:

1. Plaintiff (or prosecutor) presents his case-in-chief, then rests;

2. Defendant presents his case-in-chief, then rests;

3. Plaintiff (or prosecutor) presents his case-in-rebuttal;

4. Defendant presents his case-in-rebuttal (sometimes called his "case-in-rejoinder");

5. Each side presents further cases-in-rebuttal (again sometimes called cases-in-rejoinder).

To put this in graphic terms: The order of proof at trial goes like this:

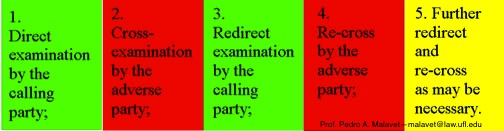

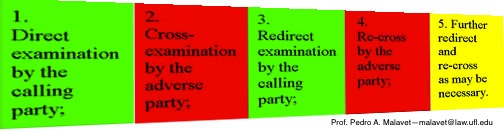

- [CB] And the order of examination is as follows:

1. Direct examination by the calling party;

2. Cross-examination by the adverse party;

3. Redirect examination by the calling party;

4. Re-cross by the adverse party;

5. Further redirect and re-cross as may be necessary. - To put it in graphic terms: The order in which a witness is examined generally goes like this:

Note that the "scope" rules would keep each succeeding block hopefully smaller and generally no greater than the one that precedes it.

Recommended Readings:

- These two books provide very good background on the mechanics of evidence:

—Thomas Mauet, Fundamentals of Trial Techniques (Little, Brown).

—Thomas Mauet, Pretrial (Little, Brown). - Francis Wellman's "The Art of Cross-Examination," originally published in 1903 and later in the early 1930s, is now available in paperback in a recent reprinting. It has some very interesting cross-examinations.

- For those looking for more reading (which I really do not recommend) you might choose one of the Hornbooks.

- McCormick On Evidence, by Thomson-West, is a good basic hornbook that is easy to read and quite good.

- Mueller & Kirkpatrick, our casebook authors, have a hornbook of their own, also published by Aspen. It is similar to the casebook, erudite and complex.

- There is also a very good multi-volume Federal Evidence—Third Edition (2007), published by Thomson-West. I recommend sparing use of this for very specific questions.

- On the canned outline side, I have always liked the Federal Rules of Evidence nutshell, though I must confess that it has gotten a bit bloated in recent years.

- I also highly recommend the DC Public Defender Service Criminal Practice Manual, available for download in PDF format for free:

http://www.pdsdc.org/LegalCommunity/TrainingCPI.aspx

I.B. Making The Record and Admitting Evidence

Regarding our readings:

It is important to distinguish between the "Official Record" and the "Trial Record".

Keep in mind that this introductory chapter is an overview of the context, the mechanics, and most importantly, the language of Evidence. While we may not discuss each term in class, you must familiarize yourself with the vocabulary of evidence that will be used for our discussion in the future. For example.

- [CB] The "official record" of a trial actually comprises five different kinds of material:

- [CB] 1. The pleadings. In civil actions these include complaint and answer, and often third-party claims, counterclaims (sometimes called cross-complaints), cross-claims, and answers to these. In criminal actions the pleadings include the indictment or complaint and the plea of the accused (usually entered orally and recorded in a verbatim transcript).

- [CB]2. Filed documents. The record includes all other papers filed in Court-such as motions and accompanying briefs, documents seeking and providing discovery, jury instructions, and court orders.

- [CB] 3. The record of proceedings. One of the most important parts of the record is the verbatim memorial of what transpires in the courtroom when the action is tried. It captures what is said by the parties, witnesses, and court in public session.

- [CB] 4. The exhibits. The record includes all the physical exhibits offered during trial (much is documentary, but some may be other kinds of physical objects), when these have been identified by one of the parties and lodged with the court, whether or not actually "admitted" for consideration by the trier of fact.

- [CB] 5. Docket entries. Finally, the record includes the court's own "ledger" of the proceedings -the "docket" or "docket book" kept by the clerk of court, which contains dated line items entered in chronological order from the beginning to the end of the proceedings (that is, from summons and complaint or indictment through judgment, post-trial motions, and notice of appeal).

Types of trial evidence:

- [CB][Testimony or Testimonial Evidence] Almost always, the bulk of the trial (in terms of time spent) involves the presentation of live testimony by witnesses.

I pointed out the American bias in favor of testimonial evidence. Note that testimonial evidence may be given in direct or cross-examination. Cross-examination allows you to ask leading questions, although you can ask leading questions of any witness that is declared "hostile" even on direct (FRE 611(c)).

Note that testimonial evidence can be direct eyewitness testimony of the occurrence (e.g., someone who saw Lt. Manion shoot Barney Quill), or direct testimony regarding an important fact (e.g., Barney Quill died of five gunshot wounds), or foundational, i.e., leading to the admission of tangible evidence (like the coroner identifying his report or the photographer identifying the pictures that he took).

- [CB]"Real evidence" refers to tangible things directly involved in the transactions or events in litigation-the defective steering assembly involved in the accident, the weapon used in the homicide or armed robbery, the wound or injury suffered by the claimant, the written embodiment of the terms of agreement.

- [CB] As the name implies, demonstrative evidence is tangible proof that in some way makes graphic the point to be proved. It differs from real evidence in that it is created for illustrative purposes and for use at trial, and it played no actual role in the events or transactions which gave rise to the lawsuit. Diagrams, photographs, maps, and models are all within the present category. So are computer-aided reconstructions, which can depict in color and from multiple perspectives an automobile accident or a crime, such as a robbery or murder or assault. See generally Fred Galves, Where the Not-So-Wild Things Are: Computers in the Courtroom, The Federal Rules of Evidence, and the Need for Institutional Reform and More Judicial Acceptance, 13 Harv. J.L. & Tech 161 (2000).

- [CB] Writings are one kind of physical evidence that generally must be introduced at trial rather than proved by means of testimonial description. Often writings amount to real evidence because so many transactions generating lawsuits involve documents. But often writings provide a means to prove what someone has said about a matter in dispute: Laboratory reports and medical records, for example, are routinely admitted into evidence as proof of the matters that they relate.

For example: The gun actually used by Lt. Manion to kill Mr. Quill is "Real Evidence". The photographs of the murder victim (Barney Quill) are demonstrative evidence. The Coroner's report admitted into evidence is documentary evidence, or a writing, which can also be either "Real Evidence' (e.g., the contract in a breach case), or, as is the case here, documentary evidence used to support, and often to supplement, the witness' testimony.

The distinction between writings and demonstrative can be found in the words "graphic" and "statements". Since the writing is not being used for its "graphic" content, but rather because of the "statements" made therein, it is not really "demonstrative evidence," as that term was defined by the authors. But it can be something prepared for the trial, to explain important issues or facts, such as the coroner's report here, and any other expert report.

Problem I-A: How did it happen: the Scope of direct/cross-examination

- [CB] To each question Barton's counsel objects, "Improper as beyond the scope of direct, your honor." How should the judge rule in each instance, and why?

- What arguments do you expect from Barton and Felsen?

- To the authors' questions, I added:

Will the testimony be received anyway?

When? [FRE 611(b)]

The Authors' Answers:

- (1) Was Dreeves seeing Barton socially? The question is proper because the scope-of-direct standard does not reach matters of credibility. See FRE 611(b). A social relationship might incline Dreeves (consciously or not) to help Barton. FRE 611(b) expresses an absolute judgment that the calling party cannot delay exploration of credibility.

- (2) Had Barton turned around to look out the back window? Proper handling of the second question depends on how we interpret scope-of-direct. A narrow interpretation would confine the cross-examiner to the "points raised" on direct (color of light), in which case the cross is beyond the scope. A broader interpretation would let the cross-examiner ask about the "transaction described" on direct (what was going on in the intersection?), in which case the question is proper. An even broader interpretation is possible, under which the cross-examiner could ask about any "issue affected" by the direct. *** Felsen might also argue that the question tends to impeach Dreeves: If he was watching Barton, he couldn't know whether Felsen ran a red light, so the question raises "matters affecting the credibility of the witness" under FRE 611(b). ***. Barton's argument seems stronger: She is trying to prove Felsen's negligence, and should be allowed to arrange her proof during her own case.

Frankly, I disagree. I believe most courts would take the "transactional" view. Additionally, if the witness is testifying about something he saw, you are entitled to explore his ability to see, i.e., the reliability of the observation. If he was looking at Barton, he was not looking at the light. While this can go to credibility (he might be lying about seeing the light at all) or to causation, it is also about his capacity to see. Of course, more traditional questions in this area might be: You are wearing glasses today, were you wearing them then?

- (3) Did Barton drink wine with lunch? This question lies beyond even a generous reading of scope-of-direct. It does not focus on "points raised" on direct (color of traffic light), nor the "transaction described" (the accident), nor does it go to "issues affected" by Dreeves' testimony (Dreeves described Felsen's negligence, not Barton's). But Felsen can argue that the Dreeves' direct testimony went to cause (Felsen running red light), and the cross-question goes to that issue (accident happened because Barton was tipsy). The substantive arguments are much the same as before. Since the third question seems less related to the direct than the second (lunchtime imbibing being removed in time and place from the accident), we would say Barton's position is even more likely to prevail: The distractive, interruptive effect of third question is greater.

- Modern appellate opinions imply that scope of direct is to be given a liberal interpretation. See Roberts v. Hollocher, 664 F.2d 200, 203 (8th Cir. 1981) ***.

We will spend much more time on this subject when we reach Chapters VII and VIII. However, my question is intended to bring you into the real world. We can (and later we will) develop the limitations imposed by the "scope of direct" rule, but even if the court finds these questions to be beyond the scope of direct, it would almost certainly allow them to be asked in support of Felsen's affirmative defense (and probably his counter-claim that Barton's negligence caused the accident). The question then becomes WHEN? Technically, the court could make Felsen wait until Barton is done with her case in chief, recall Dreeves and ask him the questions on his direct examination of a hostile witness. But, in a simple case like this one, that is highly unlikely to occur. The court would simply allow the questioning of Dreeves to be completed all at once. See FRE 611(b)[2].

However, the distinction might really make a difference in the timing in a case like say the DuPont fire litigation. There, the trial lasted 14 months and the judge was careful to allow the testimony to cover only certain areas, even if that meant recalling witnesses. In that case, weeks might be spent talking about the persons who died in an elevator, and, during that time, no references might be made to the persons who died in the casino area or in the hotel lobby. The complexity of the case often imposed such limitations.

Annotated Rules: You should get used to my habit of annotating the Rules. I will annotate and number the sentences in many of the rules in order to make our discussion more accurate. In Federal Rule of Evidence 611, pay special attention to Rule 611(b), which I have divided into 611(b)[1] and 611(b)[2].

Rule 611. Mode and Order of Examining Witnesses and Presenting Evidence

- (a) Control by the Court; Purposes. The court should exercise reasonable control over the mode and order of examining witnesses and presenting evidence so as to:

- (1) make those procedures effective for determining the truth;

- (2) avoid wasting time; and

- (3) protect witnesses from harassment or undue embarrassment.

- (b) Scope of Cross-Examination. [1-A] Cross-examination should not go beyond the subject matter of the direct examination and [1-B] matters affecting the witness’s credibility. [2] The court may allow inquiry into additional matters as if on direct examination.

- (c) Leading Questions. Leading questions should not be used on direct examination except as necessary to develop the witness’s testimony. Ordinarily, the court should allow leading questions:

- (1) on cross-examination; and

- (2) when a party calls a hostile witness, an adverse party, or a witness identified with an adverse party.

Alternative ways or looking at 611(b):

- After the very good questions today, and after some further discussion during office hours, let me offer this annotated version of Rule 611(b):

- (b) Scope of cross-examination. [1-A] Cross-examination should be limited to the subject matter of the direct examination [conducted by the party that called the witness] and [1-B] matters affecting the credibility of the witness. [2] The court may, in the exercise of discretion, permit inquiry into additional matters as if on direct examination [by the cross-examining party who now changes capacities (or, if you prefer hats) to become the directly examining party, sooner, rather than later].

- Additionally, if you think about this from a civil procedure perspective, consider if the Defendant is [1] putting the plaintiff to her obligation to prove her case (in which case the questioning falls under 611(b)[1]), or [2] is himself trying to meet his burden of proving his affirmative defense, but doing so sooner rather than later (which is what 611(b)[2] gives the Court the discretion to allow).

Credibility vs. Reliability? or Credibility IS reliability or worthiness?

- If we look at the entire sentence (611(b)[1]) as allowing the cross-examining party to "test[] the meaning and limits of testimony, along with the knowledge, capacity and truthfulness of witnesses" (Mueller & Kirkpatrick, Evidence 654 (hornbook) (2nd Ed. 1999)) then the question becomes, which parts of the rule are we discussing as to each of those ways to evaluate the reliability of the testimony?

- Credibility Defined

“Worthy of belief”

Credibility includes anything that is properly challenged through impeachment, which means that it includes both intentional (the witness lied) and involuntary (the witness was mistaken) lack of accuracy.

- Credibility Defined

We will return to this question when we get to Chapters VII and VIII. Consider as well Rules 601 (competency of witnesses, note that competency and capacity are NOT synonymous) and 602 (personal knowledge required for testimony, except for experts).

I.C. How Evidence is Excluded, etc.

Why Require Objections?

1) To avoid endless litigation

2) To help the court

3) To help the opposing sideThe Objection should be:

1) Timely

2) Well-Grounded [x]Another view is that the objection:

1) Must be made

2) Must be timely

3) Must be well-grounded

BIG IDEA: You are entitled to a fair trial, not to a perfect one.

- [CB-Objection must be made] Perhaps the one practice known to everybody is that lawyers object when they want to keep evidence out. You have probably concluded that there must be a reason and that failing to object must carry a cost. Right on both points. [FRE 103(a)(1) (objection required to appeal admission)] [FRE 103(a)(2) (offer of proof required to appeal exclusion)] [FRE 103(b)]

- [CB] The objection must be timely, meaning that it must be raised at the earliest reasonable opportunity. Thus an objection to testimony by a witness should usually be stated after the proponent has put a question but before the witness answers. (If the witness "jumps the gun," perhaps with the connivance of the other lawyer, the objection can be stated after the fact, when it becomes a "motion to strike.") The obvious drawback of this "after objection" is that the jury has heard the answer, so an instruction to disregard may be ineffective, even counterproductive (emphasizing the point to be forgotten). Hence the objecting party often couples a motion to strike with a request for a mistrial, arguing that the damage cannot be undone, and therefore that the trial must begin anew before another jury. You can probably guess why this part of the motion is not likely to succeed.

- [CB] And the objection should include a statement of the underlying reason ("ground")

- [CB] The general objection. If overruled, a general objection does not preserve for review whatever point the objector had in mind, and in this sense it gives less than maximum protection.

- [CB, Motion in Limine] Often a party anticipates that particular evidence will be offered to which he will object. Sometimes he anticipates that an item of proof that he plans to offer will meet serious objection from the adversary. In either case, he may want to obtain a ruling in advance, and the mechanism of a "motion in limine" (literally, "at the threshold") provides the means. This procedural device is sometimes authorized by statute or rule, and it exists by common law tradition in almost all other jurisdictions (including the federal system).

- [CB, fn.] 6. The motion to suppress evidence, which is generally authorized by specific provision in the rules of criminal procedure (see, e.g., FRCrimP 12(b)) and routinely made by the defense as a means of asserting rights based upon the Fourth and Fifth Amendments, is the best known instance of this procedure in operation.

- [CB] From the standpoint of the trial judge, the motion may seem to seek an "advisory opinion" that she is loathe to provide. It grates on her judicial temperament to be asked to decide a point not yet actually presented, and its very isolation from the trial may persuade her that she does not yet know how the issue should be resolved.

- [CB] The counterpart to the objection is the offer of proof. Making an offer of proof is not nearly so ingrained in the popular image of lawyers as objecting, but it is equally important, and failing to make offers when necessary is a common and serious shortcoming. Here is the basic point: A lawyer faced with a ruling excluding evidence must make a formal offer of proof, if he wants to preserve the point for later appellate review, which means demonstrating to the trial court exactly what he is prepared to introduce if permitted. [FRE 103(a)(2)]

- [CB, Judicial Mini Hearings] Objections and offers of proof can involve court and parties in what amounts to "mini-hearings" raising all sorts of questions. ***

- [CB] Obviously the judge has a role to play. But does he decide these questions himself? Or just screen them, passing them to the jury if a reasonable person could decide them either way, on the basis of the evidence or common sense and experience?

- [CB] Rule 104 describes the functions of judge and jury in deciding evidence questions. Rule 104(a) says that the judge determines "preliminary questions" -witness competency, privilege, and "admissibility of evidence." Rule 104(b) says it is different when "relevancy" turns on ''fulfillment of a condition of fact."

- [CB, Consequences of Evidential Error] Few trials make it from beginning to end without error on points of evidence, and claims of evidence error are commonplace in appeals. It is doubtful that perfection in administering evidence law may be had at all, let alone at a price worth paying. There are three main causes of imperfection, and for each the system has developed an adaptive technique that helps separate errors requiring correction from those that do not.

- [CB] First, some evidence rules are slippery or complex.

- [CB] Second, some evidence rules are framed only as vague standards, and close appellate scrutiny would make no more sense than trying to fix a computer with a wrench.

- [CB] Third, ours is an adversary system, which places the lion's share of responsibility for the conduct of trial in the litigants themselves (acting through their lawyers).

[CB] Kinds of error.

- In explaining what they do, reviewing courts classify evidence errors in four categories:

- [CB] One is "reversible" error, which refers to the kind of mistake which probably did affect the judgment. Generally the term also means that appellant took the necessary steps at trial to preserve his claim of error (usually by raising an appropriate objection or making a formal offer of proof).

- [CB] Another is "harmless" error, meaning the kind of mistake that probably did not affect the judgment. This label expresses the reviewing court's conclusion that appellant has not shown that a ruling affected the verdict.

- [CB] The third is "plain" error, meaning the kind that in the estimation of the reviewing court warrants relief on appeal even though appellant failed at trial to take the steps usually necessary to preserve its rights (objecting or making an offer of proof). *** See Rule 103(d).

- [CB] The fourth is "constitutional" error in criminal cases, which usually means a mistake by the trial court in admitting evidence for the prosecution that should have been excluded under the Constitution.

- [CB] HARMLESS. The circumstances that most often turn the poignant into the bland -reversible into harmless error- are three in number:

- [CB] First is the "cumulative evidence" doctrine, which supports affirmance despite errors by the trial court both in admitting and in excluding.

- [CB] Second is the "curative instruction" doctrine. When a trial judge commits an evidence error, he may be able to avoid reversal by means of an instruction to the jury. When the risk is great that evidence admitted on one point or against one party may be improperly considered by the jury as proof on a different point or against another party, a "limiting" instruction may be sought (see FRE 105), and such instruction is usually viewed as effective, thus disposing of any contention on appeal that the evidence was used improperly.

- [CB] Third is the "overwhelming evidence" doctrine. If a reviewing court concludes that evidence properly admitted supports the judgment below overwhelmingly, generally it affirms, even in the face of errors admitting or excluding evidence that might otherwise have been considered serious. The opinions seem almost to suggest that the evidence was such as to invite a directed verdict.

- [CB, Obtaining Review] Evidence rulings are, for the most part, prime examples of the nonappealable interlocutory order.

- [CB, Interlocutory Appeals] There are two important exceptions to the pattern sketched above -two instances where interlocutory appeal is commonly permitted. One arises when a person claims a privilege and refuses to answer despite an order of the trial court directing him to do so, and the other involves pretrial orders suppressing evidence in criminal cases. [E.g., Hickman v. Taylor (work-product)]

- [CB] Suppression motions. In criminal cases in federal court, applicable statute paves the way for government appeals "from a decision or order . . . suppressing or excluding evidence . . . not made after the defendant has been put in jeopardy and before the verdict or finding on an indictment or information" if the U.S. Attorney certifies that the appeal has not been taken "for purpose of delay and that the evidence is a substantial proof of a fact material in the proceeding" (18 U.S.C. §3731) . Many states have similar statutes.

Problem I-B: He didn't object!: Answers by the Authors

- *** The question is whether Dreeves would have more than a reasonable chance if he is permitted to appeal on the basis of Barton's objection. It seems that Dreeves should be allowed to do so. Requiring each party to reiterate objections adequately made by similarly-situated parties would clutter and burden the proceedings. Dreeves cannot be accused of sitting on his rights because he might reasonably conclude that advancing the same argument that Barton made would not affect the ruling.

- (2) Did the error in admitting Hill's testimony hurt Dreeves (affect a "substantial right" of his)? The question raises issues of substantive law. Negligence by Barton in speeding might bar or reduce her recovery as driver of the Fiat, but cannot properly bar or reduce Dreeves' recovery (the doctrine of imputed negligence having been repudiated in this situation). ***

- If Dreeves is to win reversal, he must argue that the jury likely found for Felsen because it concluded that Barton's speed (not Felsen's running the red light) caused the accident. (Maybe Felsen entered the intersection legally and paused to turn left when the light changed, so he was not negligent or did not cause the accident.)

- *** Of course Dreeves should not be permitted to raise on appeal an argument not advanced by Barton, such as "unfair prejudice" (risk that jury will misuse evidence that Barton was speeding by denying recovery to Dreeves). If Dreeves relies on Barton's objection, he must confine his argument on appeal to the argument made by Barton at trial. ***

Rule 103. Rulings on Evidence

- (a) Preserving a Claim of Error. A party may claim error in a ruling to admit or exclude evidence only if the error affects a substantial right of the party and:

- (1) if the ruling admits evidence, a party, on the record:

- (A) timely objects or moves to strike; and

- (B) states the specific ground, unless it was apparent from the context; or

- (2) if the ruling excludes evidence, a party informs the court of its substance by an offer of proof, unless the substance was apparent from the context.

- (b) Not Needing to Renew an Objection or Offer of Proof. Once the court rules definitively on the record — either before or at trial — a party need not renew an objection or offer of proof to preserve a claim of error for appeal.[This is the amended language that resolved an existing lagoon].

- (c) Court’s Statement About the Ruling; Directing an Offer of Proof. The court may make any statement about the character or form of the evidence, the objection made, and the ruling. The court may direct that an offer of proof be made in question-and-answer form.

- (d) Preventing the Jury from Hearing Inadmissible Evidence. To the extent practicable, the court must conduct a jury trial so that inadmissible evidence is not suggested to the jury by any means.

- (e) Taking Notice of Plain Error. A court may take notice of a plain error affecting a substantial right, even if the claim of error was not properly preserved.