Evidence Exam Feedback Memo

Spring 2014

LAW 6330 (4 credits)

Professor Pedro A. Malavet

Spring 2014

INSTRUCTIONS FOR EXAM REVIEW

Procedure for Examination Review. I will be available to discuss examination results during the Spring semester, beginning after Friday, September 12, 2014, when I post this feedback memorandum on my website.

You may pick up the exam from my Assistant, Ms. Karen Kays, in room 343. Please bring your exam number with you, as I keep them organized by exam number; you will also be asked for your student ID. You may make a copy of your exam answer and keep it for your records, but you have to return the original to me because faculty are required to keep exams for a few semesters.

If you are not physically in Gainesville, you are welcome to contact Ms. Kays via email and we will upload a scan of your exam to the course Sakai Site, and you will be able to access it using your gatorlink ID.

Review Policy. Examination review is a good way to learn from your mistakes, and from your successes. I encourage you to review my feedback memo and your exam. I will be happy to sit down and discuss substantive matters with each student. I will first tell each of you what you did right. I will also gladly suggest ways to improve your exam-taking abilities.

No Grade Changes. I want to make one thing perfectly clear: I have never changed an exam grade for any reason other than a mathematical error. Barring mathematical errors, your grade is not going to be changed. Grading is a time-consuming and difficult process. The only fair way to do it is to grade in the context of each class. I look for a fair overall grade distribution and follow the rank of each student within the class in awarding the final grade.

Results in General. The TRUE/FALSE was on the higher side of the usual averages at 10.95 of 12. The average score for the essay was just a shade under 246 points out of 540. Better than average as well.

Exceeding the Word Count. Many students exceeded the word limit, but it was by an amount so mathematically insignificant that it did not affect their grade. Only one of the 60 students who took the exam exceeded the limit by an amount that resulted in a significant deduction.

Class participation deduction. All students were able to meet the minimum class participation requirement. That is one of many benefits in a smaller class.

Specific Feedback

Rather than transcribing the full exam, I will again simply provide the answers here in two forms. First, a short grading sheet, and second the explanation of the True/False and some specific thoughts on the actual examinations and their successes and shortcomings.

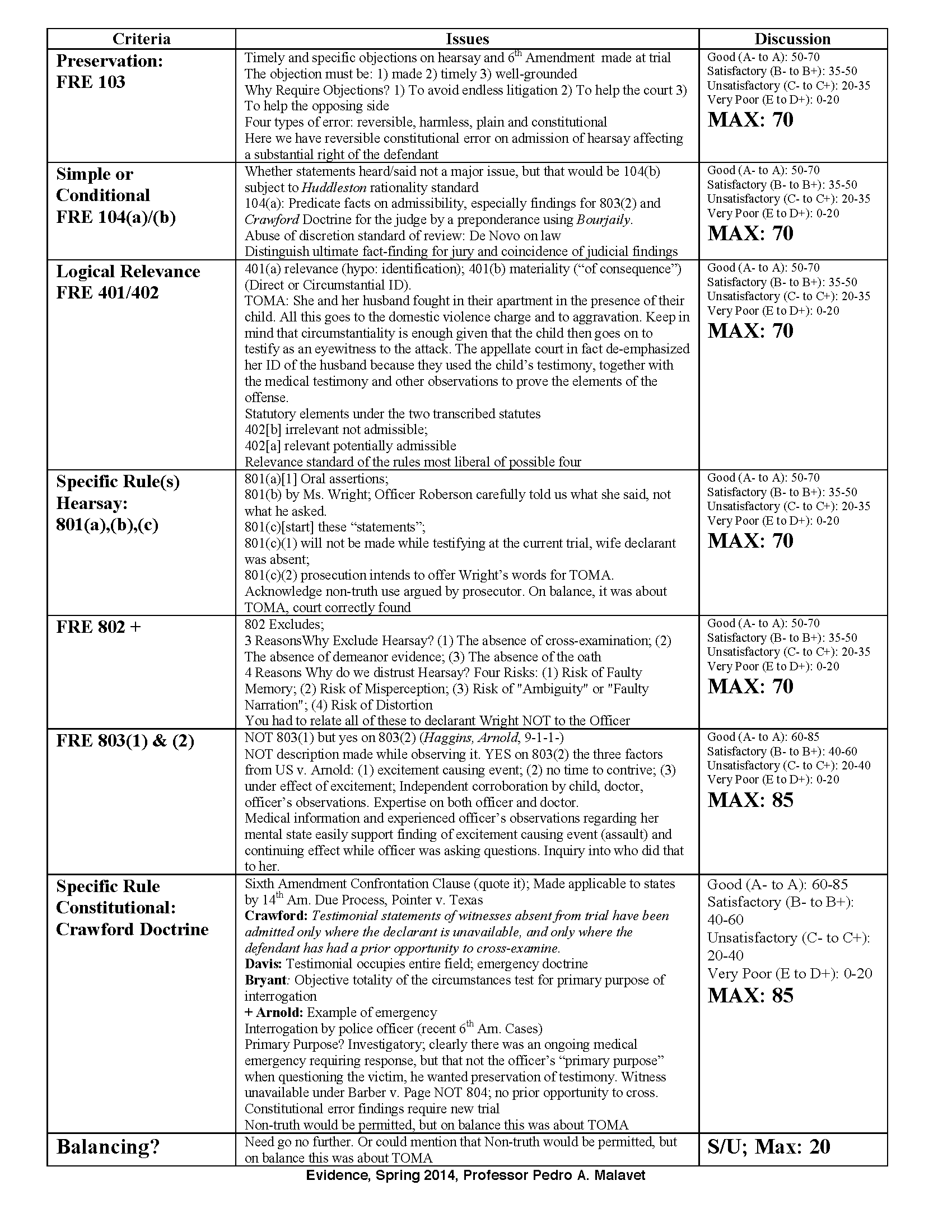

Grading Rubric for Spring 2014 Exam

True/False

1. False

2. True

3. False

4. True

5. True

6. False

7. True

8. True

9. False

10. True

11. False

12. True

Grading Rubric for the Essay

[Click here to see the rubric in PDF]

The True/False Explained

- Answer: FALSE.

My Buckaroo Banzai (Adventures of Buckaroo Banzai Accross the Eighth Dimension) scenario. As we discussed in relation to U.S. v. Lightly, at page 528, the presumption of competency of FRE 601 applies even to persons about whom we have questions regarding their mental health. If the court then found that, though insane, the witness could understand the oath, had memory of the relevant facts, and could communicate what he saw or did, he may indeed be found to be a competent witness, therefore the alternative that the court must find him not competent to testify is false and the may find him competent is true. - Answer: TRUE.

By taking out the word “only” I made it a true statement. The “path of least resistance” remains compliance with Frye. Daubert simply makes it easier when you cannot reach that high standard. The old Frye standard may still produce admission, it is just that after Daubert and Kumho Tire, Frye is not the only basis for admissibility. The sentence is basically a quote from the Frye case that I can manipulate with the introduction or omission of a single word such as “only” or “never”. - Answer: FALSE.

Back to the negative to make it False under the “Plain Error” language of FRE 103(e), which is still available to the court, provided that a substantial right be affected. - Answer: TRUE.

Other than going from “John Tenant” to “Juan Valdez” (I was in Colombia when I wrote the exam), the same as last year. My usual “are you paying attention to ‘unfairly’ prejudicial” question. The court in Bryan v. State, 450 N.E.2d 53, 57-58 (Ind. 1983), found that the evidence was indeed prejudicial, as any inculpatory evidence in a criminal trial would be, but it was not unfairly prejudicial. Therefore, it passes muster under, or, more accurately, it ought not be excluded using FRE 403. The court’s analysis demonstrates legitimate relevance and probative value, and none of the factors in favor of exclusion. Also, there is no mention of “substantially outweighed” even if you were to read “prejudice” as being the same as “unfair prejudice”. Admit. - Answer: TRUE.

Express assertion of intent, a specific state of mind. This clearly comes from Pheaster and our discussion of FRE 803(3). Larry’s statement of intent to go to Sambo’s, or here to the gym, offered to prove that intent, is dependent on the truth of the matter asserted and is thus hearsay under FRE 801(a),(b), (c). It will be clearly admissible for that limited purpose under 803(3) but that is not the question. - Answer: FALSE.

New sport, as an homage to the final four performance, but this is still nonhearsay circumstantial evidence of state of mind. A variation on “I am Napoleon Bonaparte.” As we discussed in class repeatedly, this statement is offered to prove lack of mental capacity (and generally absolutely ridiculous on multiple levels that should be clear to any Gator), and it is nonhearsay.

As I noted in class, this is the position taken by our casebook authors and by me in this area. Others, such as professor Graham, take the position that this should be treated differently (though they ultimately agree that it is nonhearsay).

This one is more akin to the “I am Woody Allen” in our class problem, since of course Coach Donovan, luckily for the Gator Nation, is a very real person. But he is not a UConn junior (had to change sports for some good news). Naturally these are laboratory conditions, in a real case, this statement would have to be accompanied by evidence that he was not kidding. You may notice that which university the allegedly mentally ill student comes from is our bowl opponent. - Answer: TRUE.

I changed the offense to assault and the opening of the door related to Don’s propensity for violence as opposed to thievery. The prosecution may rebut by attacking Don’s character trait and violence is indeed the “pertinent [character] trait” here. The government may offer this evidence under 404(a)(2)(A)[ii] which allows a direct attack on defendant when he presents evidence of his own good character. The rebuttal is proper because of the rule’s language regarding “if admitted” and here the rebuttal goes to the pertinent character trait: violence. - Answer: TRUE.

I used “homicide” as I did last year, therefore triggering 404(a)(2)(C). I simply changed the result to “may be admitted”, thus changing it to a true statement. FRE 404(a)(2)(C) allows the prosecution to rehabilitate the character of a homicide victim based on the admission of any evidence that the victim was the first aggressor, not just a character attack on the victim. The character response to ANY charge that the victim initiated the violence is only permitted in homicide cases, which this one is. All else is governed by (a)(2)(B). - Answer: FALSE.

The opposite of the general rule to make the statement false. “May generally” is a different thing, but must always or must never are simply too broad. Once again consistent with the restyling using “must” for being obliged to do so. Bruton, tells us that while the general rule is that juries follow instructions, there are occasions when that cannot be assumed, so “never” and “always” are false, and “generally” is true. Finally, the reason advanced by the majority in Delli Paoli was to tie the result to maintenance of the jury system. "Unless we proceed on the basis that the jury will follow the court's instructions where those instructions are clear and the circumstances are such that the jury can reasonably be expected to follow them, the jury system makes little sense." We agree that there are many circumstances in which this reliance is justified. This is a clear statement of the general rule regarding instructions, but it does not always apply. - Answer: TRUE.

The rule does say “may” and this is one of the exclusion rationales. Once again, I have updated the 403 exclusions to account for the restyled language. Consistent with restyling, I am also using “may” for “has the authority to” and “must” for “is compelled” or “is obliged” to do so. - Answer: FALSE.

Problem 2-C. The court may admit flight as evidence of guilt and that is in fact the most common result as decided in Commonwealth v. Booker, 436 N.E.2d 160, 162-164 (Mass. 1982). Myers is inconsistent with Booker, and probably the better result, but there is no absolute bar and in fact, as discussed in class, evidence of flight is routinely admitted. Did you think that 403 exclusion made this “false”? The possibility that the evidence might be excluded under FRE 403, even that the better result would be to exclude under FRE 403 balancing, should tell you that “may admit” is possible and therefore “not allowed to admit” is false. Otherwise the same as last year, except for the homage to Dallas. - Answer: TRUE.

This is from Problem 5-R. The criminal case exception of 408(a)(2) only applies when (a) evidence is indeed offered in a criminal prosecution, AND (b) the negotiating party was a government agency acting in its official capacity. That is precisely the case here with the state attorney general enforcing state securities laws. Straight-forward example of the exception. I changed John Ponzi, who gave a type of such schemes a name, with the name of the lead character in The Wolf of Wall Street.

Some Reactions to the Essays

Just about every student properly read the facts as the findings of fact by the court of appeals, thus not overly complicating the question.

FRE 103. There were many awkward references to 103(b) that referenced the notice of appeal. That is not what 103(b) addresses. It simply addresses the “definitive ruling” questions during the pretrial or trial process, i.e., motions in limine, or objections that are overruled and the testimony continues, as Officer Robersons’s testimony clearly did.

Evidential Hypo. The fact-pattern does not elaborate on what Officer Roberson testified in detail, it only hints at the description of the vehicle and how that led to the high-speed chase, which the prosecutor argued allowed him to make non-truth use of that hearsay. Roberson does talk about asking about the suspect of stabbing her, and that she said in response to that her husband and her (Ms. Wright) had fought and that the child was present during the argument. Multiple elements of both statutes are implicated here. If you then concluded that the officer testified to her description of her husband as her assailant and of the car, that was fine. But if you chose to take a more hedged approach, that was fine too.

FRE 801(a),(b),(c), TOMA: She and her husband fought in their apartment in the presence of their child. All this goes to the domestic violence charge and to aggravation. Keep in mind that circumstantiality is enough given that the child then goes on to testify as an eyewitness to the attack. The appellate court in fact de-emphasized her ID of the husband because they used the child’s testimony, together with the medical testimony and other observations to prove the elements of the offense. The officer emphasized the car description and the prosecutor gave three alternatives for its admission to explain why the police attempted to stop the car and a pursuit ensued. He was clearly trying to tie up the elements of the fleeing offense. In fact, the court ruled that admission of the testimonial hearsay was harmless error because there was overwhelming independent evidence of defendant’s guilt.

FRE 802, Hearsay Rule Policy. When discussing both the reasons to exclude hearsay and four reasons we distrust hearsay, it is critical that you articulate how they might apply to the facts of this case. It is then crucial that you focus on how they relate to declarant Wright. There is a lot of confusion on this, with people often focusing on the declarant as to the three reasons and on the witness relaying it to the jury as to the four reasons we distrust hearsay. I tried to emphasize this, as do the casebook authors at the start of Chapter 3: notice that all seven factors are explained as they relate to declarant Bystander’s statements that are relayed to the jury by witness Faraway. If you did not focus thusly, you were graded down.

FRE 803(1) and (2). The critical questions for me were in the 803(1) vs. (2) discussion and the corroboration of the elements of 803(2) as well as of the content of the statements for reliability purposes. A few people took the position that the medical information was not admitted testimony. That was a poor reading of the fact-pattern. I gave you a straight-forward findings of fact for an appellate decision, I did not try to distinguish admitted or excluded. Just the record. But if you chose to take that view, you could not just ignore it especially at the 803(2) stage, when the medical evidence corroborates the declarant’s condition, and it was also relevant at the Crawford stage to establish that there was an ongoing medical emergency. Attempting to ignore those facts was just a critical error. The point was not was there an emergency, the point in the Crawford section was if the officer was attempting to deal with that emergency when questioning Ms. Wright, or rather if his primary purpose was to gather investigatory and prosecutorial facts. I very much emphasized that in my discussion of Michigan v. Bryant, where in my view the majority simply got the primary purpose of the interrogation conclusion wrong, even though declarant clearly was in a medical emergency or at least in need of medical attention.

Sixth Amendment. The primary purpose question was critical of course. There is undoubtedly an ongoing medical emergency under these facts, Mrs. Wright was severely injured and in need of emergency medical treatment. But that is just not the only question under the Crawford doctrine, especially after Mich. v. Bryant introduces the objective totality of the circumstances test. The question is was the police officer’s interrogation of the witness primarily directed to addressing the ongoing emergency, or rather was it directed at gathering facts about the suspect and the crime for investigatory and prosecutorial purposes.

The prosecutor was emphasizing that Wright gave officer Roberson a description of the car in which the defendant had fled. Keep in mind that they had the child, RJ, as an eyewitness to the attack and plenty of personal observation by the officer of Ms. Wright’s injuries and the Medical testimony regarding her injuries. She provided the motive (they fought) and the description of the vehicle that led to the attempted stop and the fleeing charge that defendant was facing.

Why I selected this case. What attracted me to this case was the professionalism of all involved as it was reflected in that very short transcript of Officer Roberson’s testimony. All the professionals were acting as such.

Officer Roberson assessed the situation when he arrived in the apartment complex and realized that he was not able to do much for Ms. Wright’s medical condition, but he could engage in good-old-fashioned-police-work. And so he did. He ensured that he got information that would lead to the capture and prosecution of the perpetrator of the crime.

In court, Officer Roberson was a well-prepared, disciplined, professional witness. He was so carefully avoiding the use of “I said to her” or “I asked her” or even “She said”. And in a very short sentence he got into the record pretty much everything that the prosecutor could get out of Ms. Wright’s words. Fantastic. “With regard to what information did she give me about the person that did this (leave her bleeding from 30 stab wounds) to her, she advised me her and her husband had got into an argument at their apartment, which was actually across the parking lot, apartment 5B, I do believe, was their apartment. And that they had a son in the room, that was in the living room.” Identification, location, motive, relationship, household relationship and the child witness. Pretty much all the elements of the two major offenses for which I gave you the statutes in one answer.

The prosecutor had clearly prepared his witness and was concerned that Ms. Wright’s statements might get excluded. And he seemed especially keen to use an effect on listener theory at least to justify sending what she said over the radio to lead to the police chase that is the basis for the fleeing charge. And he was prepared to argue in the alternative under 803(1) and (2).

Defense counsel was proactive even when the witness was being so very careful about the statements, trying to present it as evidence he gathered. And he kept adjusting to what the prosecutor and judge did.

And the judge was paying attention to the objections, and to the counter-argument from the prosecution and clearly there were at least two possible emergencies going on here, so finding that the police were motivated by that was certainly not silly.