Evidence Exam Feedback Memo

Fall 2013

LAW 6330 (4 credits)

Professor Pedro A. Malavet

Fall 2013

INSTRUCTIONS FOR EXAM REVIEW

Procedure for Examination Review. I will be available to discuss examination results during the Spring semester, beginning after Friday, February 7, 2014, after post the feedback memorandum. Exams and the respective Feedback Memorandum will be available beginning on that date, after I post this memo to the website.

You may pick up the exam from my Assistant, Ms. Karen Kays, in room 343. Please bring your exam number with you, as I keep them organized by exam number; you will also be asked for your student ID. You may make a copy of your exam answer and keep it for your records, but you have to return the original to me because faculty are required to keep exams for a few semesters.

Ms. Kays is out on Friday, February 7, 2013, and I will be taping my lessons for the law school's Introduction to the Legal System of the United States MOOC today. Therefore, you will be able to start picking exams on Monday the 10th.

If you are not physically in Gainesville, you are welcome to contact Ms. Kays via email and we will upload a scan of your exam to the course Sakai Site, and you will be able access it using your gatorlink ID.

Review Policy. Examination review is a good way to learn from your mistakes, and from your successes. I encourage you to review my feedback memo and your exam. I will be happy to sit down and discuss substantive matters with each student. I will first tell each of you what you did right. I will also gladly suggest ways to improve your exam-taking abilities.

No Grade Changes. I want to make one thing perfectly clear: I have never changed an exam grade for any reason other than a mathematical error. Barring mathematical errors, your grade is not going to be changed. Grading is a time-consuming and difficult process. The only fair way to do it is to grade in the context of each class. I look for a fair overall grade distribution and follow the rank of each student within the class in awarding the final grade.

Results in General. The TRUE/FALSE was on the higher side of the usual averages at 10.7 of 12.

Exceeding the Word Count. Many students exceeded the word limit, but it was by an amount so mathematically insignificant that it did not affect their grade. Only one of 104 students exceeded the limit by an amount that resulted in a significant deduction.

Class participation deduction. Eight (8) students failed to comply with the minimum class-participation requirement. I took off 5% for those who had only one sign-up (5) and 10% for those who had none (3). This requirement is clearly stated in my syllabus and I repeatedly announced it in class. Moreover, I had multiple days when I did not have enough students signed up and had to ask for additional volunteers during class.

Pencil. I actually forgot to penalize for pencil use, so a couple of you got lucky.

Specific Feedback

Rather than transcribing the full exam, I will try something new this year. I will simply provide the answers here in two forms. First, a short grading sheet, and second the explanation of the True/False and some specific thoughts on the actual examinations and their successes and shortcomings.

Grading Rubric for Fall 2013 Exam

True/False

1. False

2. True

3. True

4. False

5. True

6. True

7. True

8. False

9. False

10. False

11. False

12. True

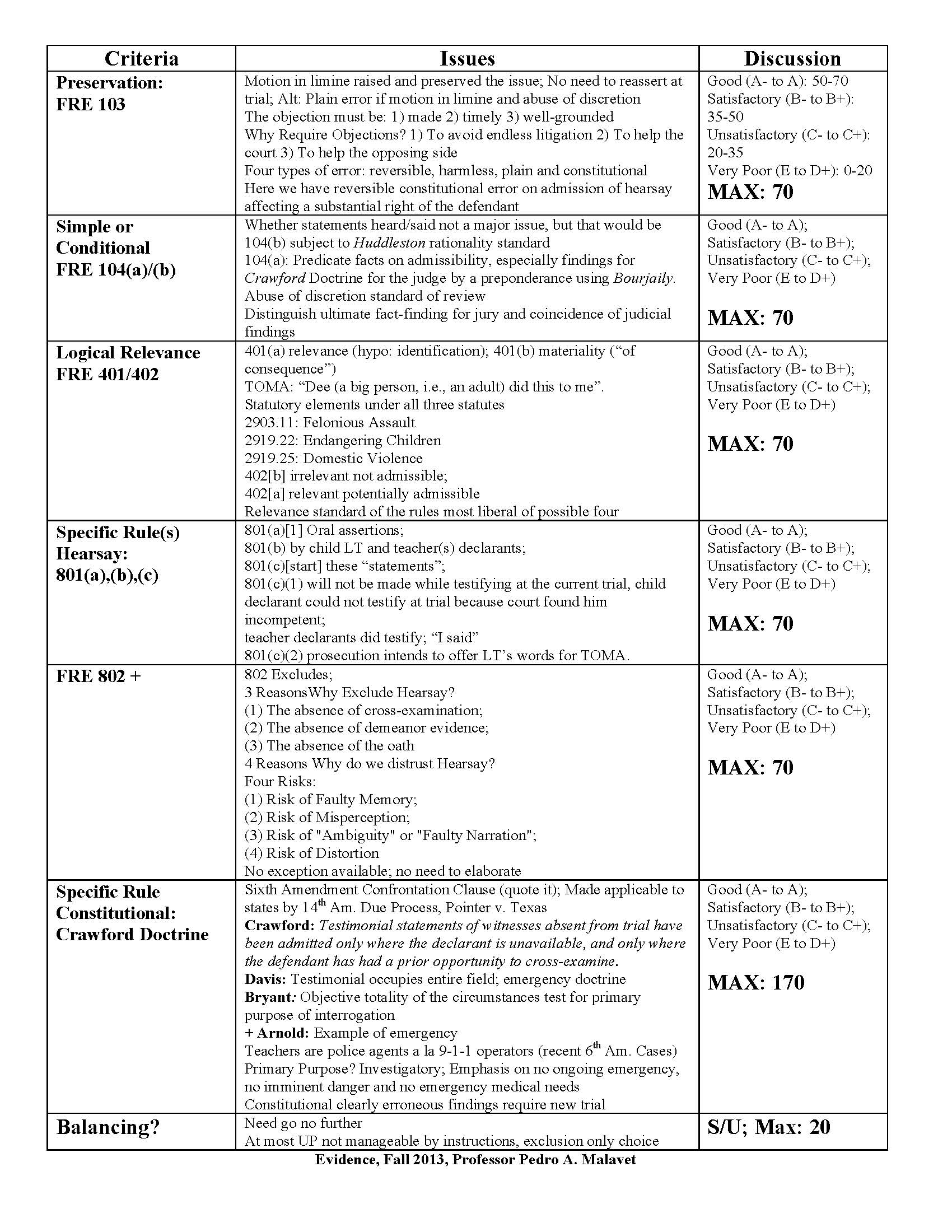

Grading Rubric for the Essay

[Click here to see the rubric in PDF]

The True/False Explained

1. Answer: False. Duck Soup and Verbal Act both lead us non-truth use from which guilt may be circumstantially inferred. Facts from the classic movie comedy Animal House.

2. Answer: True. My current version of U.S. v. Lightly, loosely based on the Adventures of Buckaroo Banzai Accross the Eighth Dimension. These are the facts of US v. Lightly. As we discussed in relation to U.S. v. Lightly, at page 528, the presumption of competency of FRE 601 applies even to persons about whom we have questions regarding their mental health. If the court then found that, though insane, the witness could understand the oath, had memory of the relevant facts, and could communicate what he saw or did, he may indeed be found to be a competent witness, therefore the alternative that the court must find him not competent to testify is false and the may find him competent is true.

3. Answer: True. FRE 413. Updated to fit the restyling. In a sexual assault prosecution certain evidence of another offense of offenses of sexual assault may be admitted for any purpose to which it is relevant, including the Action in Accordance inference, not an offense of any kind. Back to “of any kind”.

4. Answer: False. The old Frye standard may still produce admission, but after Daubert and Kumho Tire it is not the only basis for admissibility. The sentence is basically a quote from the Frye case.

5. Answer: True. I changed this question from last year to the positive to make it True under the “Plain Error” language of FRE 103(e), which is still available to the court, provided that a substantial right be affected.

6. Answer: True. My usual “are you paying attention to ‘unfairly’ prejudicial” question. The court in Bryan v. State, 450 N.E.2d 53, 57-58 (Ind. 1983), found that the evidence was indeed prejudicial, as any inculpatory evidence in a criminal trial would be, but it was not unfairly prejudicial. Therefore, it passes muster under, or, more accurately, it ought not be excluded using FRE 403. The court’s analysis demonstrates legitimate relevance and probative value, and none of the factors in favor of exclusion. Also, there is no mention of “substantially outweighed” even if you were to read “prejudice” as being the same as “unfair prejudice”. Admit.

7. Answer: True. This is nonhearsay under the non-truth use of Effect on Listener. Item no. 2 in the Hearsay Quiz and a variation that I always reference in class. And future groups might watch out for the Bill Murray cab driver variation of “I should not have drank all that cough syrup” from Stripes!

8. Answer: False. This is nonhearsay. A variation on “I am Napoleon Bonaparte.” As we discussed in class repeatedly, this statement is offered to prove lack of mental capacity (and generally absolutely ridiculous on multiple levels that should be clear to any Gator), and it is nonhearsay.

- As I noted in class, this is the position taken by our casebook authors and by me in this area. Others, such as professor Graham, take the position that this should be treated differently (though they ultimately agree that it is nonhearsay).

- This one is more akin to the “I am Woody Allen” in our class problem, since of course Mr. Manziel is a very real person. But he is not an FSU junior (no bowl game for us this year, so I had to vary my pattern). Naturally these are laboratory conditions, in a real case, this statement would have to be accompanied by evidence that he was not kidding. You may notice that which university the allegedly mentally ill student comes from is our bowl opponent.

9. Answer: False. I changed the offense to robbery and the opening of the door related to Don’s honesty. The prosecution may indeed rebut by attacking Don’s character trait, but violence and robbery are not in the same category of “pertinent [character] trait” thus making the character trait not pertinent. The government may offer this evidence under 404(a)(2)(A)[ii] which allows a direct attack on defendant when he presents evidence of his own good character. The rebuttal is proper because of the rule’s language regarding “if admitted” but it still has to be about a pertinent character train, and violence and robbery are not a proper match.

10. Answer: False. This year I changed “assault” to “homicide”, therefore triggering 404(a)(2)(C). The question is deceptively similar to last year, but I changed “assault” back to “homicide” which changed the proper answer. FRE 404(a)(2)(C) allows the prosecution to rehabilitate the character of a homicide victim based on the admission of any evidence that the victim was the first aggressor, not just a character attack on the victim. However, you must keep in mind that character response to ANY charge that the victim initiated the violence is only permitted in homicide cases. All else is governed by (a)(2)(B) and there is no character attack by defendant to open the door for this rehabilitation of the victim here. The rule is clear on the matter.

11. Answer: True. Back to the general rule to make the statement true. “May generally” is a different thing, but “must always” or “must never” are simply too broad. Once again consistent with the restyling using “must” for being obliged to do so. Bruton, tells us that while the general rule is that juries follow instructions, there are occasions when that cannot be assumed, so “never” and “always” are false, and “generally” is true. Finally, the reason advanced by the majority in Delli Paoli was to tie the result to maintenance of the jury system. "Unless we proceed on the basis that the jury will follow the court's instructions where those instructions are clear and the circumstances are such that the jury can reasonably be expected to follow them, the jury system makes little sense." We agree that there are many circumstances in which this reliance is justified. This is a clear statement of the general rule regarding instructions, but it does not always apply.

12. Answer: True. The rule does say “may” and this is one of the exclusion rationales. Once again, I have updated the 403 exclusions to account for the restyled language. Consistent with restyling, I am also using “may” for “has the authority to” and “must” for “is compelled” or “is obliged” to do so.

Some Reactions to the Essays

Paraphrasing the rules instead of quoting them. One very common general mistake was to paraphrase rules rather than quoting them. This was especially prevalent in the Crawford discussion. You had your outline in your rule book, or you should have it, so why not quote the case text instead of trying to paraphrase, which often produced subtle and less-than-subtle errors in the description of the rule.

Discussing Irrelevant Rules. Despite my instructions not to go into the use of FRE 807, some students wasted their time doing just that. Even more wasteful were attempts to discuss other hearsay exceptions.

FRE 103. On the 103 discussion you could use the motion in limine and the appeals court use of the abuse of discretion standard to infer that the issue was properly preserved by defendant and there was no need to renew at trial. Then follow that with the substantial right discussion and the standard of review that is applied under Crawford (abuse of discretion).

Alternately, you could use 103(e) to make a plain error argument. As long as you did not ignore the fact that there was a defense motion in limine, and that the standard of review is abuse of discretion, either tack would score well.

FRE 104. A very common mistake in the 104 discussion was to associate coincidence only with 104(b). Coincidence arises whenever there is overlap between judicial and jury decisions as to admitted evidence and is indeed highest with 104(a) decisions, which is why the judge says nothing to the jury about her findings.

There continues to be confusion about 104(b) and the jury’s ultimate responsibility for fact-finding. Conditional admissibility is a very special and specific situation where the jury is instructed to use evidence in a particular order. But the jury has total responsibility for fact-finding generally beyond 104(b).

FRE 401. Choosing the wrong language. One common example of describing a principle incorrectly came up often in discussions of FRE 401. Students wrote something like “Past courts have shown that (rule 401) comes with a liberal standard.” The rule makers had to choose among four possible standards and the rule adopts the most liberal one is the correct description.

Hearsay. Some students made very good arguments for treating the initial statements to Whitley about falling down as circumstantial evidence of state of mind. This would take a lie as evidence that the child had been coached (programmed) or intimidated (fear) and that this circumstantially tied to Darius Clark.

A very common error was to discuss the hearsay risks as they attach to the witnesses, Whitley and Jones, rather than to declarant LP. It was especially odd when students talked about the three reasons why we exclude hearsay and related that discussion to LP, but then switched to discuss Jones and Whitely with the four hearsay risks. Remember the discussion that opens chapter three, both the three reasons and four risks are explained as they relate to declarant Bystander, not the witness who relays them in court.

Crawford and the 6th Amendment.

The statute applies to public and private school employees. Therefore, the attempt to find some kind of public school status was confounding.

The most common mistake in the Crawford section was to fail to discuss the agency issue. The starting point given this fact-pattern is that the questioning by the teachers has to be treated as the equivalent of police interrogation. It is because the teachers, in private or public schools, are made “agents” of law enforcement by the statute, as explained by the Court. They are “deputized” by the statute, as one very good answer put it. The students who emphasized this also often used Melendez-Diaz and Bullcoming to illustrate who “state actors” or “investigators” are in the very best answers (well done!). Their questions to the child are therefore to be treated as police interrogation.

Then you reach the primary purpose question under a totality of the circumstances analysis of Bryant. The child declarant is a very good example of why it would be foolish to always focus on the declarant’s intent. A child of three is very unlikely to understand what a criminal prosecution is, let alone make statements intended to be used at a criminal trial. But the investigation aspect of this encounter is what the SC of Ohio saw as a problem. The great majority of students simply went into a discussion of “primary purpose” and the absence of an emergency without addressing the agency issue at all. This did not score well.

The finding that the child was incompetent to testify certainly makes him “unavailable” at trial by any definition of the term.

On Crawford, the fundamental question was why questions from school teachers or day care personnel would be treated as the equivalent of Police interrogation for sixth amendment purposes. Like 9-1-1 operators, the teachers are legally deemed to be agents of the police because of the statutory mandate to report suspected child abuse.

This part of the analysis was overwhelmingly weak in most exams.

Facts taken, and modified to fit examination purposes, from STATE v. CLARK, 2013-Ohio-4731. I combined the factual description made by both the majority and the dissent into a single fact-pattern.

UPDATE: SUPREME COURT GRANTED CERT

The SCOTUS ruled that the child's statements were NOT testimonial under the 6th Amendment and that Mandatory Reporting statutes do not automatically convert non-testimonial statements into testimonial statements explaining that "mandatory reporting statutes alone cannot convert a conversation between a concerned teacher and her student into a law enforcement mission aimed primarily at gathering evidence for a prosecution." Ohio v. Clark, 135 S.Ct. 2173 (2015), Alito, J., wrote for a unanimous court, with two concurring opinions.