Comparative Law Notes 11

LAW 6250

Professor Pedro A. Malavet

Class Notes Part 11

Chapter 10: Constitutional Courts, Structure and Procedure

General Comparison Chart

Posted in the course canvas page and handed out in class.

A. Structure And Function Of Constitutional Courts: An Introduction

- Constitutionalism 1:

- A. Structure And Function Of Constitutional Courts: An Introduction

Basic Question

- “Does constitutionalism require judicial review of the constitutionality or lawfulness of the acts of governments and their officers?”

- Put another way:

- Should a constitution require some type of judicial review?

- By whom? Judicial?

- For whom? Privileged of Individual applicant

Juridification

- Judicializing constitutional review

- Implies a limitation in the power of the legislative and executive branches

- A limit on the political, i.e., elected branches of government

General vs. Specialized Review

- The U.S. Supreme Court

- constitutional decisionmaker,

- adjudicator of issues of statutory interpretation under federal law, and

- the court of last resort for review of decisions in the lower federal courts

Generalist vs. Specialized

- In acting thus as a “generalist” court, the U.S. Supreme Court differs from many European constitutional courts which

- specialize in the resolution of constitutional questions, often on referral from the ordinary court system

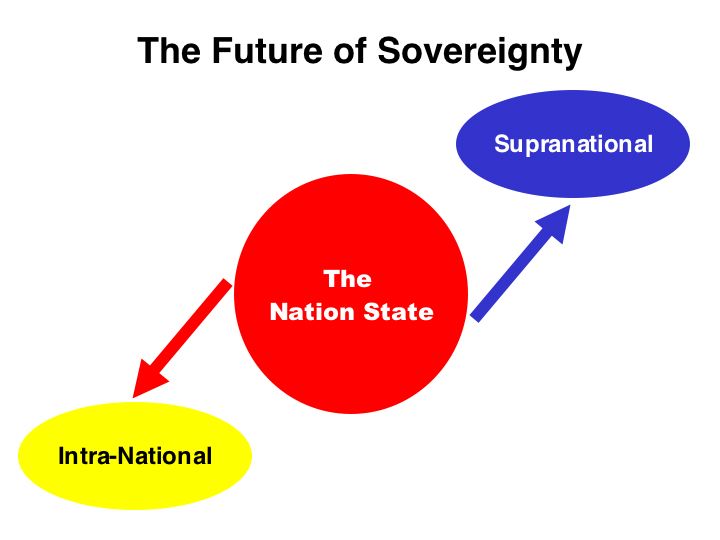

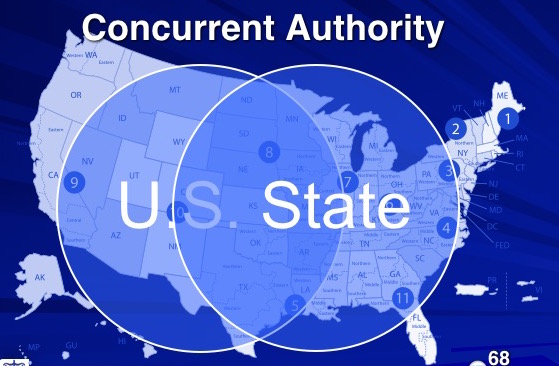

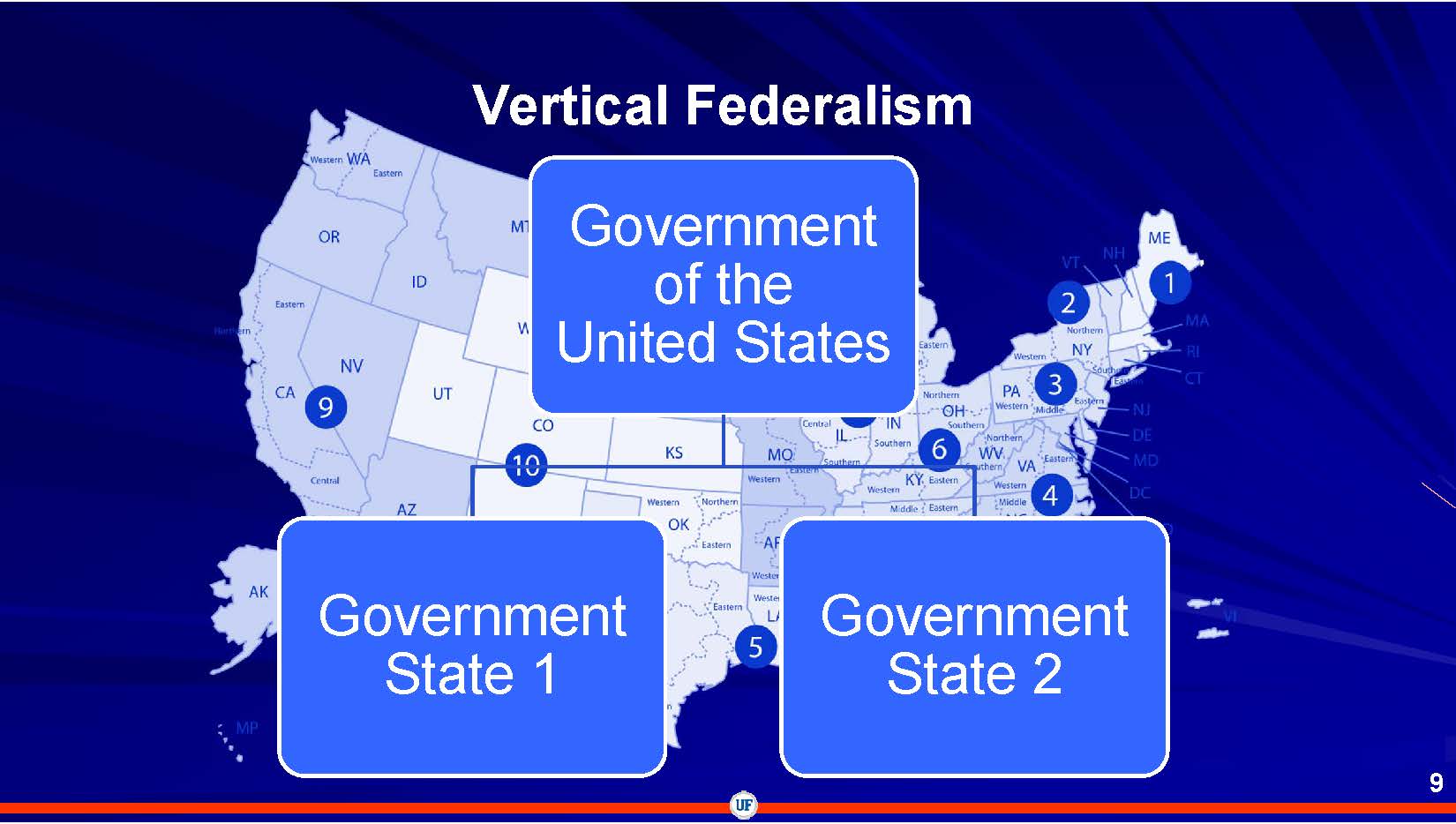

Centralized v. Decentralized

- The decentralized model (also known as the “American” or “diffuse” model involving “incidental” review) is represented by the organization of the United States’ judicial jurisdiction.

- jurisdiction to engage in constitutional interpretation is not limited to a single court.

- It can be exercised by many courts, state and federal, and is seen as inherent to and an ordinary incident of the more general process of case adjudication.

Supremacy Clause

- US Const. Art. VI, § 1, Cl 2. Supreme law.

- This Constitution, and the Laws of the United States which shall be made in Pursuance thereof; and all Treaties made, or which shall be made, under the Authority of the United States, shall be the supreme Law of the Land; and the Judges in every State shall be bound thereby, any Thing in the Constitution or Laws of any State to the Contrary notwithstanding.

Centralized v. Decentralized

- The centralized model (also called the “Austrian” or “European” model) is characterized by the existence of a special court, with exclusive or close to exclusive jurisdiction over constitutional rulings.

- Constitutional courts sit outside,

not atop ordinary court system

Centralized v. Decentralized

- “Kelsenian constitutional review provides a means of defending constitutional law as higher law, while retaining the general prohibition on judicial review.”

- Hence, only a few officials have authority to review constitutionality, and certainly not all ordinary judges

Centralized v. Decentralized Hybrid

- in which the ordinary courts may have power to refuse to apply an unconstitutional law, but only a single court has the power to declare a law invalid.

- Pioneered by Latin American countries

- Variant: Specialized chamber of the Supreme Court

Centralized v. Decentralized Hybrid

- Another type of hybrid allows lower courts to decide constitutionality claims, subject to appeal through the system up to the specialized constitutional court, which shall have the final word on the matter

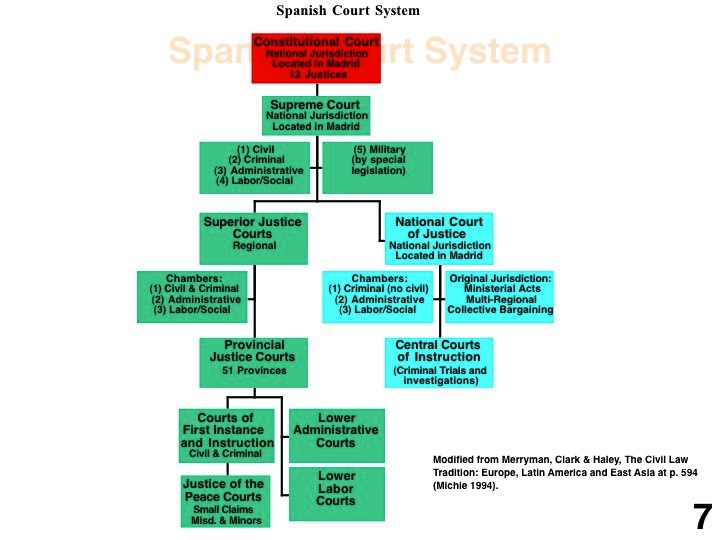

- e.g. Spain and Russia

- But note that this can create a “competition” especially between the Constitutional Court and the Supreme Court

Other Pressures

- Internally:

delays in adjudication encourage lower court judges to interpret statutes “in the shadow of the constitution” - (constitutionality review without calling it that)

- Externally:

ECHR, for example, and its effect on national adjudication, EU Court of Justice on union matters

The Role of Judges

- Cappelletti argues that constitutional adjudication “often demands a higher sense of discretion than the task of interpreting ordinary statutes,” and that the ordinary training of civil law judges does not conduce to the task of constitutional interpretation.

- Favoreu suggests as well that the election or appointment of judges in the U.S. by political branches gives them a legitimacy in constitutional interpretation that continental career judges lack.

- (Do you agree?)

Countries in Transition: Independence

- countries in transition from authoritarian regimes, it would be very difficult to implement decentralized review, since the general corps of available judges would be unlikely to have either the training or the independence from prior regimes to function with legitimacy as constitutional adjudicators. Finding a small number of respected and untainted jurists, who might constitute a centralized and specialized constitutional court, is simply more doable.

Stare Decisis

- In the United States, as in other common law countries, the doctrine of stare decisis extends the effect of rulings of law from the parties in the case before it to the broader legal community within the jurisdiction of the deciding court.

- In Europe there is no tradition of stare decisis and most constitutional courts have the effect of their decisions expressly defined by constitutional provision or law.

- Solution is to put it in a statute or constitutional provision

Abstract v. Concrete Review

- Abstract:

not in the context of case-or-controversy litigation - Usually based on petition by privileged applicants from within the executive and legislative branches

- Concrete:

individual review related to a specific case or controversy brought by party(ies) with standing - “Convergence”?

Constitutionalism:

From the U.S. with Love?

- French Constitutional Convention:

This noble idea coming from another hemisphere was to be implemented here first. We participated in the events which led North America to freedom: it shows us on which principles we should rely to keep ours. The New World on which we put chains in the past is today showing us how to protect ourselves from being chained. - The idea of review probably does originate in the US, and quickly exported to Europe, but it was not really implemented there until after WWII.

“American” Constitutional Review

- At bottom, then, there is no particular “constitutional litigation,” anymore than there is administrative litigation; there is no reason to distinguish among cases or controversies raised before the same court. Moreover, in de Tocqueville’s words, “An American court can only adjudicate when there is litigation; it deals only with a particular case, and it cannot act until its jurisdiction is invoked.”

Contrast European

Specialized Jurisdiction

- Constitutional Review is the (sometimes exclusive) prerogative of a Constitutional Court and often abstract

- Lower courts may not decide those matters at all or may be required to “refer” the question to the constitutional court

- For example, in Germany a trial court may hold a post-1947 law constitutional and continue with the case, but if it finds that the law is unconstitutional, it must stay the proceedings and make a reference to the Constitutional Courts.

European Review: Erga Omnes

- the effect of the decision is erga omnes, i.e., applicable to all, absolute.

- When a European constitutional judge declares an act unconstitutional, his declaration has the effect of annulling the act, of making it disappear from the legal order. It is no longer in force; it has no further legal effect for anybody, and sometimes the ruling of unconstitutionality operates retroactively.

- Kelsen characterized the constitutional court as a “negative legislator,” as distinguished from the “positive legislator,” the parliament.

Convergence or Coincidence? 1

- Above all, the United States and the European systems protect fundamental rights against infringement by governmental authority, particularly the legislature. The means are different, but the ends are the same and the results similar.

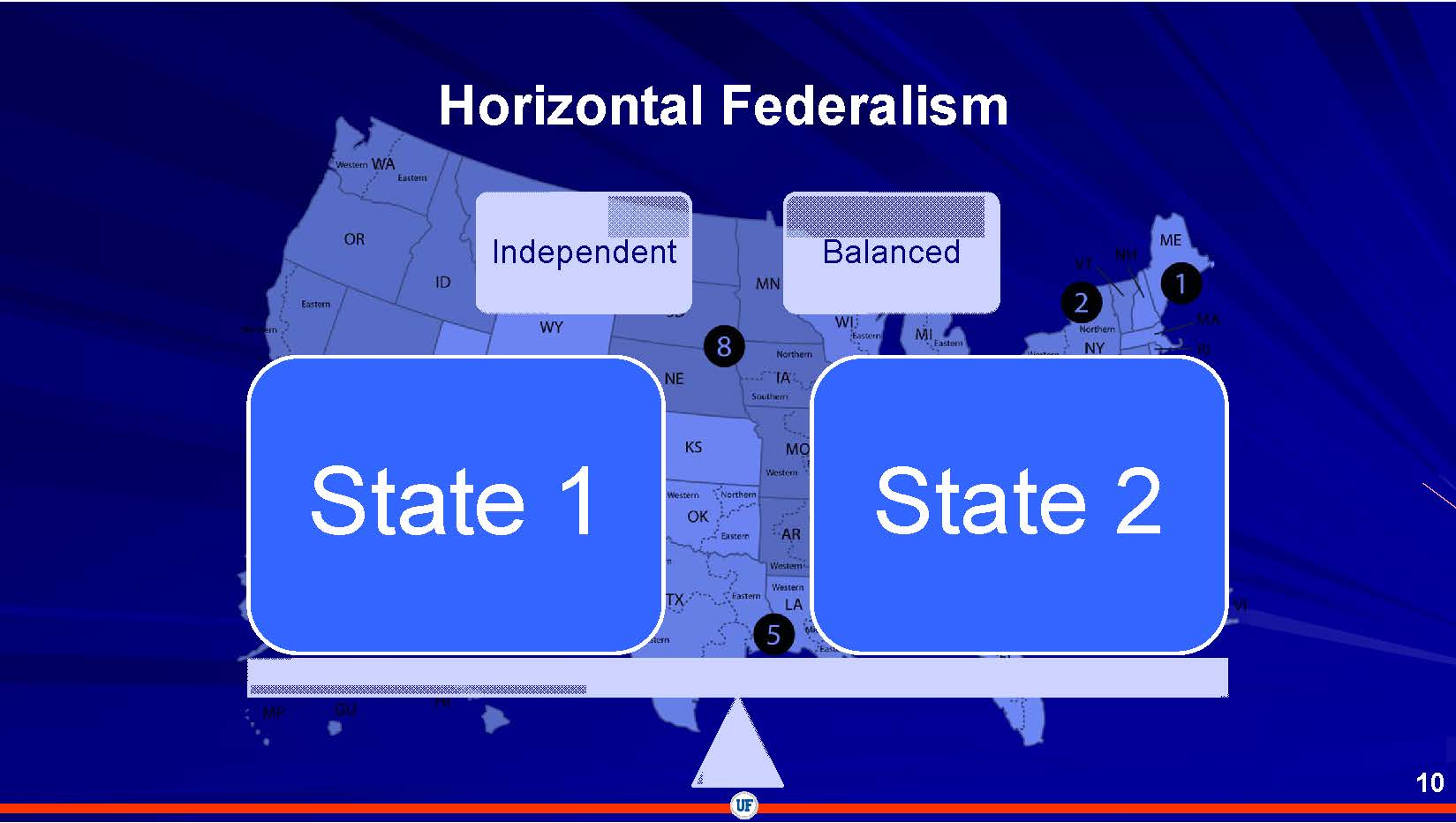

Convergence or Coincidence? 2

- Both systems generally try to maintain a balance between the state and the entities of which it is composed. In a federal state, constitutional review serves that function whether the system of review follows the United States model or the European one. The United States Supreme Court and the German Constitutional Tribunal play a similar role in maintaining the balance between the federal government and the member states.

Convergence or Coincidence? 3

- United States and European constitutional courts perform the same tasks, as contemplated by their respective constitutions, when they protect the separation of powers-the division of authority between the various organs of the state, whether between the executive and the legislature, or between the chambers of Parliament.

Convergence or Coincidence? 4

- In Europe, as in the United States, constitutional courts may have to decide electoral disputes regarding the highest positions in the state, or the arraignment of the highest political authorities.

- Constitutional courts decide political issues following legal forms.

Changing the Judicial Function in Existing Courts?

- the authors explain how reform was attempted in France, Germany and Italy by using the U.S. model as the goal

- Essentially failed results

France, Pre-WWII

- Strong push at the start of the 20th Century

- Existing Court de Cassation and Conceil D’etat seemed to avoid giving effect to unconstitutional law by interpreting so as to be within constitutional limits

- No authority (or willingness) to declare laws unconstitutional

Fascist Germany and Italy

- One item to note is that many comparativists have written about activist German judges promoting Nazi laws, and Italian conservative judges resisting Italian fascism

- Mostly during the period preceding WWII (except Italy’s pre-1956 experiment)

Failure to follow U.S. Example

- Legislative Supremacy, from Rousseau’s version of the Enlightenment

- The legislature when making law has to examine whether the law considered is consistent with the Constitution and resolve issues in that regard .... This means that interpretation of the Constitution is to be left to Parliament. Because it is exercising the powers of the sovereign, Parliament is the judge of the constitutionality of its own laws. Therefore courts are not to interpret the Constitution; at least they do not have that power in relation to the legislature.

Failure to follow U.S. Example

- A second reason for the failure of the graft [attempted import] is the inability of the ordinary European judge to exercise constitutional review.

- US: Supreme Constitution,

Europe: Supreme Legislation - Judicial “timidity”?

- The “weakness” and “timidity” of the Continental judge lies perhaps in his being a “career judge,” and not, like the United States judge, selected for the task.

- Diverse and strictly-separate judicial jurisdictions are also a challenge

- Lack of constitutional supremacy

B. Models of Constitutional Review in Contemporary Europe

Constitutionalism 2

- Models of Constitutional Review in Contemporary Europe

- Supremacy of the Constitution, particularly of individual rights

- Universal Declaration of Human Rights

- Constitutionality review becomes fundamental, but

Post-World War II

- Constitutionality review becomes fundamental, but

- Along what model?

- U.S. generalist, de-centralized and concrete review or

- European specialist, centralized and abstract?

Countries Choosing the U.S. Model

- Norway

- Denmark

- Sweden

- Switzerland

US Model: General Factors

- Mostly unified legal systems with courts of general jurisdiction

- only Sweden has ordinary and administrative courts and both may consider constitutional issues

- Decentralized review: constitutional issues can be raised in any proceeding

- Concrete review: persons with standing based on case or controversy standard must bring action

- Judge obliged to decide constitutional issue, subject to appeal

- Decision binding on courts and other branches

Norway

- Oldest, dates back to 1814

- 20-30 judicial declarations of unconstitutionality, ever

- An outdated constitution that failed to set general principles is a limitation

- “Unwritten principles which bind the legislature” mostly derived from international human rights documents, especially EConv.HR

Denmark

- Constitutional review accepted in theory

- Appears to be entirely absent in practice

- Abstention by the court gives legislative full discretion

- “unlawfulness cannot be established with the required certainty for the courts to be able to declare unlawful the provisions of law which was passed according to the Constitution”

Sweden

- Expressly provided in the Constitution since 1978

- “[I]f the provision has been decided by the Riksdag or by the Government, the provision may be set aside only if the inaccuracy is obvious and apparent”

- No case, ordinary or administrative, has found conflict between legal acts and the constitution

Switzerland

- Limited to non-federal acts by the cantons

- Review of federal acts would be “undemocratic” “judicial supremacy over the legislature”

- “Democratic liberalism” means that courts do not substitute their judgment for that of the elected branches of government, especially the legislative

European Model

- Austria

- Germany

- Italy

- France

- Spain

Austrian Constitutional Court

- Established in 1920

- Active from 1920-1938 (German takeover)

- After WWII, 1945-Present

Austrian Constitutional Court

- Jurisdiction over: elections, conflicts between courts, and litigation between the federal state and the Länder (states).

- It acts as an administrative court to review administrative acts alleged to violate rights guaranteed by the constitution.

- It acts also as a high court of justice to bring to trial the head of state or ministers accused by the houses of Parliament.

Austrian Constitutional Court: Parties

- The Court can exercise judicial review at the request of any of the following:

- Land government, higher courts, a third of the members of the National Council (or a third of the members of a Land legislature), or, under some conditions, individuals.

- The Court may also raise constitutional issues on its own initiative.

Austrian Court: Very Active

- The Court’s case law, developed over the last sixty years, is extensive, particularly in relation to fundamental rights.

- The impact of its decisions on the legal and political system is strong even though the Court’s decisions are not binding on ordinary courts, unlike the decisions of the German and Spanish high courts.

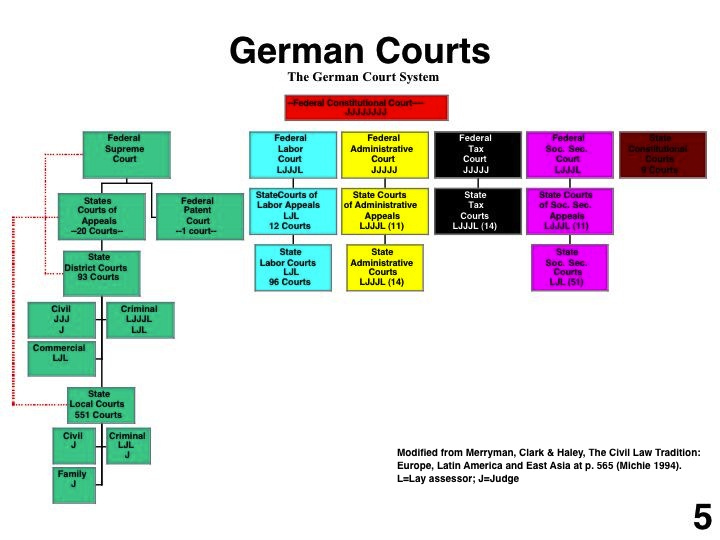

German Constitutional Court

- The German Federal Constitutional Tribunal was prescribed by the 1949 Constitution and established in 1951 (by Organic Act).

- In addition to constitutional review of legislation, it has jurisdiction to review cases involving the election of members to Parliament; to decide cases brought against the President of the Republic; to adjudicate controversies between constitutional organs, and between the Federal Republic and the Länder, or between two Länder.

- By 1999, the German Constitutional Court had decided over 100,000 cases, of which over 96% came on individual constitutional complaints.

German Constitutional Court: Parties

- Abstract Review:

Constitutional review can be initiated by the government of a Land or by a third of the members of the Bundestag in regard to a federal law (for review of a law on its face); - Concrete Review:

by reference to the Court from lower courts (for review of a law as applied); or by an individual claiming that his fundamental rights have been violated by a judgment, by an administrative act, or (under certain conditions) by a statute.

The Italian Constitutional Court

- Established by the 1947 Constitution, came into force in 1956

- Conflicts jurisdiction, allegations against President, President of the Council of Ministers, ministers, abrogative referendums, constitutional review of laws

- Courts make references to this court on constitutional questions.

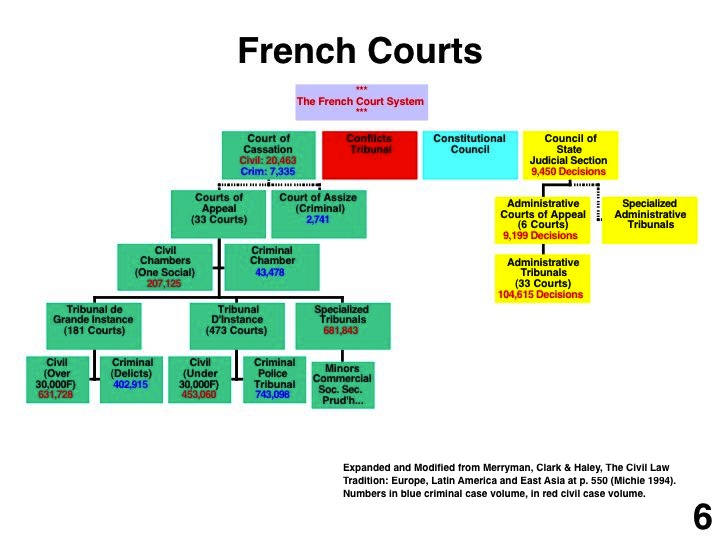

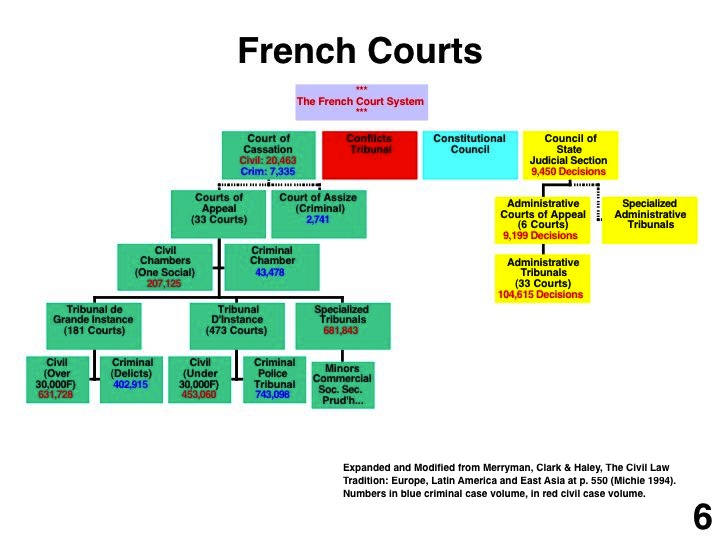

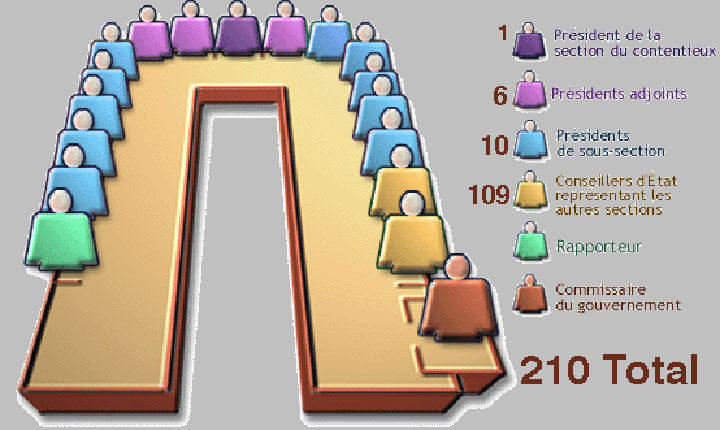

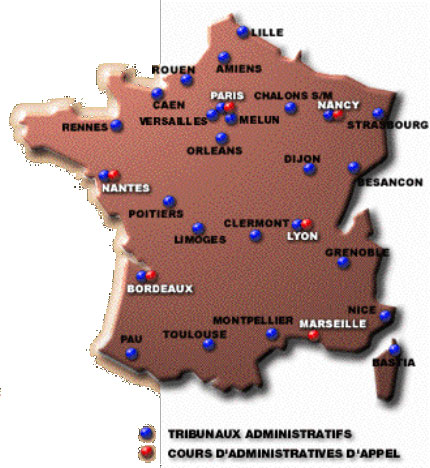

French Constitutional Council

- The French Constitutional Council was established in 1958 and came into force in 1959.

- It is composed of nine judges —three appointed by the president of the Republic, three by the chairman of the Senate, and three by the chairman of the National Assembly.

- Former presidents of the Republic are de jure members, but since 1962 none has sat on the Constitutional Council (however, former Presidents Giscard d’Estaing and Chirac have recently been recognized as a members).

French Constitutional Council

- The Constitutional Council has jurisdiction over electoral issues (elections to the National Assembly and Senate, election of the President, and referenda); conflicts regarding the division between the legislative domain and regulations (lois and règlements); the constitutionality of the rules of a chamber of Parliament; the constitutionality of international treaties; and the constitutionality of laws-upon request by one of the four highest authorities of the state (the president of the Republic, the chairmen of the National Assembly and of the Senate, and the prime minister), or by sixty members of the National Assembly or sixty members of the Senate.

Members of the

Conseil Constitutionnel

- Laurent FABIUS, appointed by the President of the Republic in February 2016.

- Valéry GISCARD D'ESTAING, ex officio member *

- Michel CHARASSE, appointed by the President of the Republic in February 2010

- Claire BAZY MALAURIE, appointed by the President of the National Assembly in août 2010

- Nicole MAESTRACCI, appointed by the President of the Republic in February 2013

- Nicole BELLOUBET, appointed by the President of the Senate in February 2013

- Lionel JOSPIN, appointed by the President of the National Assembly in December 2014

- Jean-Jacques HYEST, appointed by the President of the Senate in Octobre 2015

- Michel PINAULT, appointed by the President of the Senate in February 2016

- Corinne LUQUIENS, appointed by the President of the National Assembly in February 2016

- * Out of the former Presidents of the Republic, who are automatically members of the Constitutional Council, only Valéry Giscard d'Estaing currently sits on the Constitutional Council. Jacques Chirac and Nicolas Sarkozy have no longer sat on it since March 2011 and January 2013 respectively.

Spanish Constitutional Court

- The Spanish Constitutional Tribunal was established by the 1978 Constitution, and started its work in 1980.

- It is composed of twelve judges appointed by the king,

- four upon nomination by Congress,

- four by the Senate,

- two by the government, and

- two by the General Council of the Judicial Power.

Spanish Constitutional Court

- The Constitutional Tribunal has jurisdiction over conflicts between state authorities; the petition of amparo against administrative acts and court decisions interfering with fundamental rights; the lawfulness of treaties in the light of the Constitution; and the constitutionality of laws.

Spanish Constitutional Court: Parties

- Abstract:

issues can be raised by the President of the Government, by fifty deputies or fifty senators, by the authorities of autonomous communities, or by the people’s defender (defensor del pueblo). - Concrete:

Constitutional issues can be raised by courts when they are confronted with them during litigation.

Spanish Constitutional Court: Amparo

- an individual may invoke this writ to request the Constitutional Tribunal to assure the protection of his or her fundamental rights against an administrative act or a judgment of a court, when the ordinary courts have not provided such protection.

- In fact, the writ of amparo is invoked particularly against judicial acts.

- May be referred to full court for erga omnes effect

- NOTE: Very common in Latin America

Amparo

- Amparo cannot be invoked directly for review of the constitutionality of a statute (unlike constitutional review in the Federal Republic of Germany), but the chamber of the Constitutional Tribunal that reviews writs of amparo may refer questions on the constitutionality of an underlying statute to the full court.

- The petition of amparo is the basis of 90 percent of the registered cases.

Major Trends

- Mostly concrete review along the U.S. model

- But sheer volume presents a problem in that it takes too much time for a full court decision to be produced

- Remember that often only a full court decision has erga omnes effect

Major Trends: Separation of Powers

- In the American model, limitations on executive and legislative power have been achieved by the progressive recognition of a third power, the judiciary, described as “the least dangerous branch.” That third power does not exist in most European countries. European constitutional theory acknowledges only executive and legislative power. There is no recognition of a “judicial power” and judges do not enjoy the legitimacy and authority of their American counterparts.

Separation of Powers:

Specialized Court Only

- [The Constitutional Court] is neither part of the judicial order, nor part of the judicial organization in its widest sense: ... [T]he Constitutional Court remains outside the traditional categories of state power. It is an independent power whose function consists in insuring that the Constitution is respected in all areas.

- Referring to the Italian constitutional court

Separation of Powers Balance?

- Not between branches?

- Rather between majority and minority?

- Majority and minority in government position or elected office?

Countermajoritarianism

- In the parliamentary system of government, the governing political party or coalitions of parties, displacing both the legislative and executive powers, becomes omnipotent. The popular belief in judicial review establishes the courts, on the one hand, as the guarantors of the basic consensus on which democracy is founded, and, on the other hand, as the arbitrators that adjudge how far the reforms of regulations dictating the social, economic, and cultural life conform with this consensus, without reversing it. [E. Spiliotopoulos]

US-European Model

Similarities: Appointment

- In both cases, appointments are political-made by political authorities and taking into account the political inclinations of the judges. This is fully justified, since the democratic legitimacy of constitutional review rests upon the appointment of judges by elected authorities.

- But note lack of cooperation among branches

- One might note, however, that in Europe a large proportion of the judges are university professors.

Similarities: Convergence

- Avoidance of constitutional issues through narrow statutory interpretation

- The U.S. Supreme Court is as a practical matter limiting itself to important constitutional matters in certs

- The European courts, through citizen complaints arising during litigation, are more involved with the ordinary courts

European Advantage?

Speed and focus

- First, the European system seems to have the advantage of isolating important constitutional issues for decision by a specialized court, which is free from other duties and can devote the time required for this delicate task. The constitutionality of a national law is taken immediately to the constitutional court and does not have to go through the various steps of the jurisdictional ladder.

But what about Legal Penetration?

- On the other hand, one might ask whether —with a view to strengthening constitutionalism— the European system is as successful as is the American system in spreading constitutional rules throughout the various branches of law.

C. Structure, Composition, Appointment, & Jurisdiction:

Have you thought about the U.S. Supreme Court lately?

Constitutionalism 3

- Comparative Constitutional Look at the United States System

Questions About

Comparative Constitutionalism

- (1) whether, and how, appointment mechanisms for judges and the composition of the constitutional courts relate to the types of jurisdiction exercised by the court;

- (2) what are the benefits and costs of life tenure for constitutional court judges, and what is its relationship to the independence of the judiciary;

- (3) whether there are different “packages” of provisions concerning appointment, advancement, tenure, salary, or retirement that will foster judicial independence, and

- (4) whether an independent judiciary is necessary for a constitutional system (and, if not, what role an institutionally subordinate judiciary might play).

Another Basic Question

- “Does constitutionalism require judicial review of the constitutionality or lawfulness of the acts of governments and their officers?”

- Put another way:

Should a constitution require some type of judicial review?

Constitutional Courts Comparison Chart

Life Tenure

- Generally explained in the United States as a guarantee of independence

- Almost totally rejected everywhere else

- Mandatory Retirement Ages are much more common

- 68 in Germany

- 70 in Japan

US Const. Art. III, Sec. 1

- The judicial Power of the United States, shall be vested in one supreme Court, and in such inferior Courts as the Congress may from time to time ordain and establish. The Judges, both of the supreme and inferior Courts, shall hold their Offices during good Behavior, and shall, at stated Times, receive for their Services, a Compensation, which shall not be diminished during their Continuance in Office.

U.S. Const. Art. III, Sec. 2, Clause 1.

- The judicial Power [of the United States] shall extend to [i] all Cases, in Law and Equity, arising under this Constitution, the Laws of the United States, and Treaties made, or which shall be made, under their Authority; [ii] to all Cases affecting Ambassadors, other public Ministers or Consuls; [iii] --to all Cases of admiralty and maritime Jurisdiction; [iv] --to Controversies to which the United States shall be a Party; ***

Art. III, Sec. 2, Cl. 1 cont.

- The judicial Power [of the United States] shall extend to *** [v] --to Controversies between two or more States; [vi] --between a State and Citizens of Another State; [vii] between Citizens of different States; [viii] --between Citizens of the same State claiming Lands under Grants of different States, and [ix] between a State, or the Citizens thereof, and foreign States, Citizens or Subjects.

US Const. Art. III, Sec. 2, Cl 2.

- Jurisdiction of Supreme Court

In all Cases affecting Ambassadors, other public Ministers and Consuls, and those in which a State shall be Party, the supreme Court shall have original Jurisdiction. In all the other Cases before mentioned, the supreme Court shall have appellate Jurisdiction, both as to Law and Fact, with such Exceptions, and under such Regulations as the Congress shall make.

US Const. Art. VI, Cl 2. Supremacy.

- This Constitution, and the Laws of the United States which shall be made in Pursuance thereof; and all Treaties made, or which shall be made, under the Authority of the United States, shall be the supreme Law of the Land; and the Judges in every State shall be bound thereby, any Thing in the Constitution or Laws of any State to the Contrary notwithstanding.

Judicial Review in the U.S.A.

- Not expressed in the Constitution

- Marbury v. Madison, 5 U.S. 137 (1803), that the government of the United States is one of limited powers, that the constitution is intended to act as law in enforcing those limits, and that “[i]t is emphatically the province and duty of the judicial department to say what the law is,” and to apply the constitution as superior to “any ordinary act of legislation” in cases in which they both apply and are in conflict.

Limitations

- “Cases and controversies”

- No “advisory opinions”

- President Washington sought the justices’ advice on the effects of certain treaties and laws on maintaining U.S. neutrality. See Opinion of the Justices (Aug. 8 1793), reproduced in Richard H. Fallon, Daniel J. Meltzer & David Shapiro, Hart Wechsler’s Federal Courts and the Federal System 92-93 (4th ed. 1996).

Advisory Opinions

- The Justices explained their refusal to respond, in part, by noting that “[t]he lines of separation drawn by the Constitution between the three departments of the government ... being in certain respects checks upon each other‑and our being judges of a court in the last resort‑are considerations which afford strong arguments against the propriety of our extrajudicially deciding the questions alluded to . . . .”

Supreme Court Jurisdiction

- The Supreme Court can review all questions of federal law (constitutional, statutory, treaty, admiralty or federal common law) that were dispositive in the lower courts, as well as any other matter decided by a lower federal court, e.g., in diversity cases.

- largely discretionary; as a matter of statute, the Court gets to set its own agenda of cases that it decides on the merits.

Justices

- No specific qualification is provided

- Nominated by the President with advice and consent of the Senate

- Lifetime appointment, except upon impeachment

- Federalist 78-79 defend lifetime appointment

Senate Role in Confirmation

- The Congress has authority to change the number of justices

- Probably unlikely given the court-packing controversy

- Were you surprised that 30 of 144 nominees have been rejected?

Current Court

Confirmation Votes—DOB

- Antonin Scalia, 98-0, 3/11/1936

- Anthony Kennedy, 97-0, 7/23/1936

- Clarence Thomas, (7/7) 52-48, 6/23/1948

- Ruth Bader Ginsburg, 96-3, 3/15/1933

- Stephen Breyer, 87-9, 8/15/1938

- John Roberts, 78-22, 1/27/1955

- Samuel Alito, 58-42, 4/1/1950

- Sonia Sotomayor, 68-31, 6/25/1954

- Elena Kagan, 63-37, 4/28/1960

Other Confirmation Votes

- Rehnquist, 68-26 (1971); C.J. (1986) 65-33

- Stevens, 98-0

- Souter, 90-9

Withdrew or Failed

- Miers, 2005 Withdrew

- Bork, 1987, voted down 42-58

- 3 failed attempts to replace Fortas from 1968-70

- Abe Fortas withdrew nomination for CJ in 1968 and retired from the court

- http://www.senate.gov/pagelayout/reference/nominations/Nominations.shtml

Monaghan: Political Appointment

- First: Senate review is political, and there is no constitutional compulsion to approve

- Second: political nature of the Senate’s role, like that of the President, helps ameliorate the “countermajoritarian difficulty”: by increasing the likelihood that Supreme Court judges will hold views not too different from those of the people’s representatives, the Senate can reduce the tension between the institution of judicial review and democratic government.

Evolution of Presidential Power

- Note that the presidency was viewed as somewhat weak in the process in the 19th Century

- During the 20th Century, it can marshal many more resources

- “Marginal” Senate role?

- It takes a lot to “resist” the President in the Senate

- Really?

Monaghan Suggests

- Two limitations on judicial tenure

- Age limit

- Fixed and unrenewable term

Age Limits: Given Lifetime Appointment, consider

- There is no minimum age for appointment and there is no maximum age for service or retirement

- Was Douglas Ginsburg TOO YOUNG at 41?

- Should there be a mandatory retirement age?

- A minimum age for appointment?

- A fixed term of service?

- As to each, why?

What about a Supermajority Confirmation Vote

- Should we have a 2/3 vote?

- Epstein argues that a 2/3 vote would change the process for the better.

What about a Supermajority Confirmation Vote

- Why?

- Epstein: would not restrict the pool of serious candidates. It may, though, reduce it just enough to eliminate those who have no business’ sitting on the most important judicial body in our nation.

- Examples:

- Treaty advice and consent requires 2/3

- Amendments to the Constitution require both houses to approve by 2/3

Should we have a 2/3 vote?

- Why not? (Mark Silverstein)

- “That a politicized system of selecting and confirming our judges may mean that people of stature, a Brandeis and a Holmes, a Marshall and a Warren, do not find their way to the Court is a consequence that must be measured against a paramount commitment to self‑rule.”

Too “heterogeneous”?

- John Ferejohn and Pasquale Pasquino, Constitutional Adjudication: Lessons from Europe, 82 Tex. L. Rev. 1671, 1702 (2004).

- By contrast, they argue, in the United States, “a president whose party enjoys a majority in the Senate need not seek support from any members of the other party,” leading to the possibility of more heterogenous and sharply divided judges.

Too much public “dissent”?

- No dissents in Europe: Noting the tendency of European courts-even those in which dissents are permitted to speak with one voice, they suggest that

- [Too many here?] the U.S. Court has “gone too far in encouraging members ... to engage in public conflict,” and suggest that adoption of a supermajority voting requirement (as Epstein suggested years earlier) might lead to more self-restraint in publishing separate opinions

D. Structure, Composition, Appointment, & Jurisdiction, France (first session focused on history and ideology)

Separation of Powers in the U.S.: Graphic

France: Historical Context

- What we have already discussed:

- France was bankrupt in 1789 and the old estates, protected by the parlements, stood in the way of reform

- After revolution and terror, Napoleon as dictator and then emperor, designed modern French administration and law

- 19th Century showed radical variation between “constitutional moments” and absolute power

The Republics of France

- First 1792-1804

- coup in 1794

- “Directorate Period” from 1795 to 1799, followed by Consulate.

- ends formally in 1804 when Napoleon becomes Emperor

- Second 1848-1852

- Brief period of republicanism imposed by rioters (a special theme for the French)

- Coup in 1851

- Napoleon III ascends to power in 1852

The Republics of France

- Third 1870-1940

- Starts upon the fall of the second empire of Napoleon III

- Franco-Prussian War results in French defeat

- Paris Commune repressed (by returning former POWs back in the French Army)

- The Belle Epoque begins and with it the Third Republic; it all ends with the German blitz in 1940

The Republics of France

- Fourth 1944-1958

- Marked by deep political factionalism

- Defeat of French forces in Indochina (Viet Nam)

- Algerian independence

- Fears, and the real threat, of a military coup

Fifth 1958-Present

- De Gaulle takes over but demands a new constitution with hyper-powerful presidency

Third Republic

- Hyper-powerful Parliament

- Correspondingly weak Government (administration), President, Prime Minister and Cabinet

Fourth Republic

- In the 1950s, post-WW2 political tribalism and the challenges of Algeria and Indochina bring down the 4th Republic

- Since constitutional supremacy resided in the parliament, its failure to function well was a major problem

- This political experience shaped the Fifth Republic and its constitution

Crisis of 1958

- Morocco, Tunisia and, eventually, Algeria are lost

- Defeat in Indochina

- An army revolt in response to Algerian independence

- DeGaulle takes over as Prime Minister with emergency powers, including the power to draft a new constitution

The Constitution of 1958

- De Gaulle as Prime Minister supervises the drafting of this constitution,

- with the assistance of the Conseil D’Etat

- Legislative power limited and a more powerful presidency and government are hallmarks of the new constitution

The 1958 French Constitution

- Art. 34 provides for enumerated (and limited) power to legislate to be exercised by the Parliament

- Art. 37 gives to the President a general power to legislate by Decree. “executive legislative competence”

- Parliamentary power to dismiss the government (and call for new elections) curtailed

- President would appoint Prime Minister

Constitutionality Review

- Note that the Conseil Constitutionnelle was intended to limit legislative power vis a vis the executive

- The general judicial role was heavily limited, in reaction to the Parlements, and in particular to their abuse of the power of registration of royal decrees

- The old system of the first four republics centered on the power of the parliament, the elected legislature, is abandoned

Concrete Norm Control Unacceptable

- Debré:

“It is neither in the spirit of a parliamentary regime, nor in the French tradition, to give to the courts, that is to say, to each litigant, the right to examine the validity of a loi . . .” - Constitutional Council:

originally intended as an additional mechanism to ensure a strong executive by keeping Parliament within its constitutional role.

Limitations on the Judicial Role

- article 10 [law of 1790] that the judiciary was not “to take part directly or indirectly in the exercise of legislative power”, or to “obstruct or suspend the execution of the decrees of the legislative body”.

- Article 127 of the Criminal Code backed this up by making it an offence for a judge to interfere with the legislative power.

- Courts would not challenge legitimacy of laws.

Constitution of 1795: The Senat

- A special body of tenured appointees

- Could hear matters referred to it by the legislature, Government

- Could, in theory, quash unconstitutional actions

- Never worked in practice either under Napoleon or under the brief period of Republicanism prior to Napoleon III.

Constitution of 1852: Senat redux

- Like previous Senat, could invalidate lois prior to their promulgation, upon parliamentary or Government request

- Additional power to invalidate law after passage and promulgation upon Government or individual request

- Never put to the test even during the Second Empire

Constitutional Review Acceptable,

but by Whom?

- The executive (Napoleonic) vision: a specialized body to limit the power of the legislature

- Republican Tradition … before 1946 was that Parliament itself was the guardian of constitutionality.

- E.g., In the very first Constitution of 1791 the National Assembly was enjoined to refuse all proposals that infringed the Constitution.

- Self-limitation was the preferred institutional device for ensuring that the Constitution was respected, with an ultimate control exercised by the electorate.

The Council of the Republic

- Comité constitutionnel composed of the Presidents of the Republic, the National Assembly, and the Council of the Republic (as the Senate was called), and then seven persons nominated by the National Assembly and three by the Council of the Republic. The nominees appointed by the two Assemblies were to come from outside their membership.

- Only one matter actually referred to it

- Attempted review of Treaty of Rome (which created the EEC) failed

Rationale of Legislative Supremacy

- The legislative represents the will of the electorate

- Article 6 of the Declaration of 1789 stated that loi is the supreme expression of the volonté générale. This was interpreted as meaning that Parliament was the representative of the general will of the nation, and that its enactments thus enjoyed the status appropriate to the expression of the will of the sovereign.

Separation of Powers

- The argument from the separation of powers has two elements.

- on the one hand there is the statement of the appropriate function of each organ;

- on the other, there is the appropriate deference that must be paid by other organs of government. (p. 691)

Legislative Power

- Nothing is more natural than to make interpretation an act of the very person who made the text ... In other words, it is for the legislature, at the very moment of making laws, to examine if the loi being considered is consistent with the Constitution, and to resolve the problems that may arise on this point. The legislature interprets in this way by virtue of its popular representation.

- Judiciary should defer to this legislative power

Judicial Power as

“Conservative” Obstruction

- To Jèze, this would simply make the judiciary a block to social progress: “Against a democratic Parliament, product of universal suffrage, and against its possible will for reform, it is desired in reality to set up bourgeois judges for the defence and irreducible preservation of the possessing classes characterized as élites.” (p.692)

U.S. Supreme Court Inertia:

The French perspective

- Édouard Lambert in 1921.

- He described it as “doubtless the most perfected tool of social inertia to which one can currently resort to restrain workers’ agitations and to hold back the legislator from the slippery slope of economic interventionism”

U.S. Case Examples

Fuller, White, Taft courts

- Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 (1896) (7-1 decision written by Brown; Harlan dissented).

- Pollock v. Farmer’s Loan & Trust Co., 158 U.S. 601 (1895) (invalidating national income tax; reversed by the 16th Amendment).

U.S. Case Examples

- Anti-Trust

The ‘rule of reason’ became the standard for applying the Sherman Antitrust Act after the Court’s opinions in Standard Oil Co. v. United States, 221 U.S. 1 (1911), and United States v. American Tobacco Co., 221 U.S. 106 (1911)

U.S. Case Examples

- Lochner v. New York, 198 U.S. 45, 53 (1905) (invalidating New York penal statute forbidding employers from requiring workers to exceed 60 hours in a work week). Cf. Muller v. Oregon 208 U.S. 412, 423 (1908) (upholding law restricting women working in laundries to no more than ten hours a day).

Rejection of Court Model

- Janot, Commissaire du gouvernement:

- Such a system would be tempting intellectually, but it seemed to us that constitutional review through an action in the courts would conflict too much with the traditions of French public life. To give the members of the Conseil constitutionnel the power to oppose the promulgation of unconstitutional texts appeared sufficient to us. To go further would risk leading us into a kind of government by judges, would reduce the legislative role of Parliament, and would hamper governmental action in a harmful way

E. Structure, Composition, Appointment, & Jurisdiction, France (second session focused on design and evolution of the council as created in the 1958 Constitution)

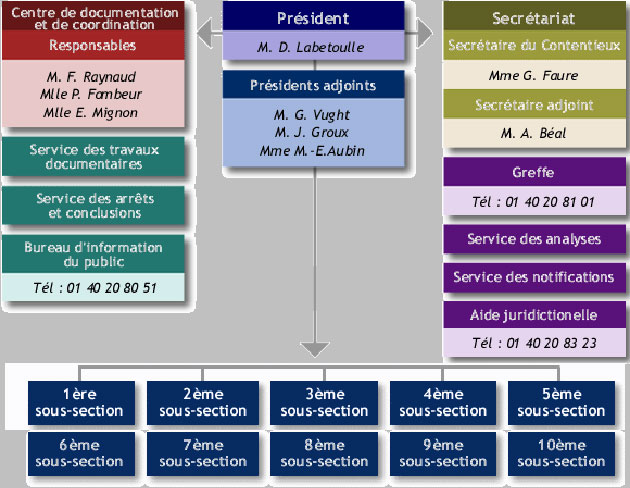

The Conseil Constitutionnel

- Created principally by Conseil d’État senior counselors drafting the constitution of the Fifth Republic

- Primarily designed to limit parliamentary sovereignty given the expanded role of the presidency

- Limited to invalidating legislative acts to avoid “gouvernement de juges”

Only privileged referrals (at first)

- President, Prime Minister, Presidents of Assembly and Senate

- Legislative minority (of one-third) expressly rejected:

- “Every time that a loi has given rise to an impassioned debate, the opposition will ... refer it to the Conseil constitutionnel, and in the end effective government will be in the hands of the pensioners who will sit on the Conseil”...

Additional References added by constitutional amendment

- 60 Parliamentarians only after 1974

- 2008-2010:

Individual Petitions permitted for the first time

Jurisdiction of the CC: Elections

- First, the Conseil is an election court and returning officer.

- It determines the existence of a presidential vacancy or incapacity, oversees the election process, and announces the results.

- It has a similar supervisory function in relation to referendums.

- With regard to parliamentary elections, it rules on disputed elections. It also rules on the ineligibility of members of Parliament.

Jurisdiction of the CC:

Presidential Emergency Powers

- Secondly, the Conseil also advises the President both when he seeks to use emergency powers under article 16 and on the rules made thereunder. Such advice is not binding, but it is of considerable authority all the same.

- The “crisis of 1961” was the second uprising of French settlers and military personnel in Algeria, which threatened an invasion of France itself.

- In October 17, 1961, Paris police, attacked unarmed Algerian demonstrators and killed dozens (low estimate at 40, high as many as 200).

Jurisdiction of the CC: Constitutionality of Treaties

- Thirdly, the Conseil may also be asked to rule on the constitutionality of treaties. Treaties are signed by the President, but require parliamentary legislation in most cases before they can be ratified. Once ratified, they have a status superior to lois (article 55). Although the Conseil constitutionnel will not strike down a loi for incompatibility with a treaty, other courts may refuse to apply it in such a case.

Jurisdiction of the CC: Treaties

- The Presidents of the Republic, the National Assembly, and the Senate, or the Prime Minister or 60 deputies or senators may refer a treaty for consideration by the Conseil to determine whether it is contrary to the Constitution.

- If it is, then it can only be ratified after a constitutional amendment has been passed (article 54).

Jurisdiction of the CC: Organic Laws

- The Conseil evaluates the constitutionality of organic laws

- These laws implement general constitutional provisions and are essential to their constitutional function

Jurisdiction of the CC: Organic Laws

- Organic laws are required in a number of areas, such as on the judiciary, on the composition of Parliament, on finance laws, and on the procedure of the Conseil constitutionnel. The process for passing them is stricter than for ordinary lois, requiring the agreement of the Senate or an absolute majority of members of the National’ Assembly (article 46). Since these organic laws may be used subsequently as a basis for judging the constitutionality of lois, and may extend the body of constitutional rules, it is appropriate that the Conseil should review them before enactment.

Jurisdiction of the CC:

Legislative vs. Executive Competence

- Primary function: to police the boundaries of the legislative competences of Parliament and of the executive.

- Three ways:

- Executive “amendment or repeal” of laws

- Referrals to protect the executive of legislative bills

- Referrals of laws

Jurisdiction of the CC:

Legislative vs. Executive

- (1) Under article 37, the Government can only amend or repeal provisions in lois passed after 1958 by way of règlement if the Conseil constitutionnel has first declassified them, in other words, if it has ruled that the provision does fall within the domain of executive legislative competence. In this way, it ensures that the Government does not overstep its competence. The Government must take the initiative, and refer provisions of lois to the Conseil if it wishes to have them declassified.

Jurisdiction of the CC:

Legislative vs. Executive

- (2) When private members’ bills or amendments are proposed in Parliament that stray into the area of the executive’s legislative competence, the Government may seek to have the proposed provisions ruled out of order. Where the President of the relevant chamber of Parliament disputes the claim of the Government, either he or the Prime Minister may refer the dispute to the Conseil, which has to give a ruling within eight days (article 41). Since 1979, this procedure has rarely been used.

Jurisdiction of the CC:

Legislative vs. Executive

- (3) Once a loi has been passed by Parliament, the Conseil has jurisdiction to rule on its constitutionality if a reference is made to it by the President of the Republic, the President of either the National Assembly or the Senate, the Prime Minister, or (since 1974) sixty members of either Assembly (article 61 § 2).

- The reform of 1974 effectively gave the opposition a chance to challenge legislation, and it has become almost the only challenger to lois.

References under Art. 61-2

- Statistical Table in Graphic

Parliament in the Fifth Republic: Defers to Executive Supremacy

- The settlement, as everyone knows, resulted in a “servile” legislature, in the famous words of François Mitterrand, in a “permanent coup d’état.”

- Formally accomplished by Articles 34 and 37 of the new constitution

- All subject matters not listed in article 34 are expressly reserved to the executive by article 37

- This line is policed by the Conseil Constitutionnel

The Conseil Constitutionnel

not Impartial? Not Judicial

- the Council was not meant to be a fair or impartial referee (any more than the constitution was designed to be fair or impartial).

- It was there as a tool of the executive

- (at least as long as he had a legislative majority)

- Council is not judicial and is not mentioned in the judiciary section of the constitution

What about Constitutional

Values vs. Formalism

- Preamble to Constitution of 1958:

The French People solemnly proclaim their attachment to the Rights of Man and to the principles of national sovereignty as defined by the Declaration of 1789, confirmed and completed by the preamble of the Constitution of 1946. - This language has been used by the Conseil in some of its most important opinions that arguably expand its powers, or at least use them aggressively

Values v. Formalism

- But the attempt to incorporate this language into Article 34 was voted down

- Nevertheless, in spite of the rejection, the Conseil itself has used the Declaration and the Preamble to the 1946 Constitution as the basis for its decisions

Valeur Constitutionnel?

- DEJEAN: For the authors of the draft, therefore, the preamble does not possess valeur constitutionnel.

- JANOT: No, certainly not.

- Dejean: Would it be a good thing to give unquestioned valeur constitutionnel to the contents of the preamble ... ? We would no longer be able to pass legislation without unhappy people referring it to the Council under the pretext that such and such a principle had been violated. We must be very prudent.

Membership in the Council

- Highly Political

- Only three judges appointed

- Presidency appointed by the President of the Republic (controls rapporteur, breaks deadlocks, sets procedures)

French Constitutional Council:

Members

- 1) All former presidents of the republic.

- 2) Nine appointed members.

3 each appointed by the- a) President of the Republic,

- b) President of the Senate,

- c) President of the Assembly.

- —(Const. Art. 42.)

Membership in the CC

- Over 18, enjoying their civil rights, no other formal pre-requisite

- Majority of appointees are professional politicians selected on the basis of party-affiliation

- 24% have been advisors to politicians

- A few judges, law professors and former parliamentarians

Presidential Appointment

- Overwhelmingly former ministers, especially former Prime Ministers

- Generally within the President’s long-term inner-circle

- Path to retirement?

Appointment: National Assembly

- Appointments made by presidents of the National Assembly have been the most unambiguously “political,” if political is understood to mean the appointment of full‑time professional politicians.

Appointment: Senate

- In contrast, presidents of the Senate have manifested great independence vis‑à‑vis the executive and have, overall, opted for higher standards of legal expertise.

- Of twelve members appointed, ten had been either professional lawyers (six), law professors (three), or judges (two) or a combination. Still the majority even of these had engaged in substantial political activities.

- Of the past six appointees‑going back to 1968‑all had been former parliamentarians, bringing the total to seven of twelve.

French Const. Article 62

- [1] A provision which has been declared unconstitutional may not be promulgated or put into effect.

- [2] The decisions of the Constitutional Council shall not be subject to review. They are binding on governmental, administrative and judicial authorities.

Possibility of Individual Referrals?

- Note the interesting discussion at pages about the possibility of allowing litigants to challenge the constitutionality of laws during ordinary and administrative proceedings, by asking the high courts in those jurisdictions to refer a question to the council.

- Failed in the 1990s

- Succeeded in 2008

Marbury vs. Madison of France?

- Freedom of Association case

- 1971 decision incorporated individual rights

- By 1987 “Fundamental Rights” accounted for forty percent of annulments

- 1974 reform has led to increased litigation

- By 1987 parliamentary references accounted for eighty percent of decisions dealing with ordinary laws

- Since 1979 46 of 48 decisions nullifying laws have been initiated by parliament

Context of the

Freedom of Association Case

- Simone de Beauvoir and Michel Leiris had attempted to form the Association of Friends of the Cause of the People under the old law.

- The prefecture denied them the certificate of incorporation.

- The administrative courts reversed that decision as an abuse of power.

- The legislature quickly moved to amend the law.

Freedom of Association Case

- The council was summoned upon request of the President of the Senate.

- Bill discussed by both the Senate and the National Assembly, amending prior law on freedom of association, by placing prior restraints on that right.

- Clearly politically motivated and directed against the left.

Importance of the Freedom of Association Case:

- 1) Demonstrates the effectiveness of the French system of prior constitutional control;

- 2) The legislator is no longer supreme, must answer to the Constitution;

- 3) constitutional jurisprudence is an important source of French law.

Impact of Council Decisions

- On the Legislature

- Clearly binding by operation of the enabling constitutional provisions.

- On the Administrative Courts

- Lack power to declare laws unconstitutional, but might follow interpretation to declare act ultra vires.

- On the Ordinary Courts

- Similar to Administrative, but less likely to do so.

Conseil Constitutionnel Graphics:

-

École Nationale d’Administration

Paris since 1978. Façade. -

Paris: Rear View

-

Paris: Main Lobby

-

Strasbourg: City

ENA Built here in 1991 -

Strasbourg: Front Entrance

-

Strasbourg: Interior

F. Structure, Composition, Appointment, & Jurisdiction, Germany

Map: Europe: WWII--1939-42

Map: Europe, WWII--1942-45

Graphic: Separation of Powers

“Germany”

- Did not exist at start of 19th century

- Mid-19th Century: confederation reduces number of states from over 300 to 40

- Failed constitutional reform in 1848 included U.S.-style judicial review

- Prussian-led North German Confederation in 1867, Wilhelm I as Kaiser, Otto von Bismarck as Chancellor

- Defeated the French in 1867 and ends with defeat of WWI

Prior to Weimar:

Empire Constitution

- Constitution, President, Chancellor and bicameral legislature

- Reichstag (an elected body) though with limited power

- and the Bundesrat (members appointed by the state governments)

- Neither a bill of rights nor judicial review of legislation.

Weimar Republic

- Created following German defeat in WWI

- Constitution, President, Chancellor and bicameral legislature

- Bicameral Parliament:

- Reichstag (an elected body) and the

- Bundesrat (members appointed by the state governments)

- included a bill of rights, and was interpreted to permit judicial review.

Weimar Republic:

Structural Problems

- While the chancellor and the cabinet were appointed by the president, they could be removed from their offices by the Reichstag without the designation of a successor; conversely, the

- President could dissolve the Reichstag, and frequently did.

Weimar Republic:

Amendments by Accident

- Apart from formal amendments, the legislature could, by passing an otherwise unconstitutional law by a two‑thirds vote, alter the constitution without explicit amendment

- Professor Currie asserts that in this way, “the Constitution could be altered entirely by accident and ... no one could determine what the Constitution provided by reading it ....”

Nazis, 1933-1945

- Began with elected representation in the 1930s

- By 1933 the aging Hindenburg appoints Hitler as Chancellor

- Emergency power provisions of the constitution are then used to declare state emergency

- Legislative then, legally-speaking, essentially gives unlimited power to rule by decree

Modern Germany

- Following Germany’s defeat in World War II, West Germany (the portion of Germany under the control of the western allies) adopted a new constitution, the Basic Law of 1949.

- When East and West Germany reunited in 1990, they did so under that Basic Law.

- But they used accession of new states, rather than reunification provisions

Basic Principles of German Basic Law

- 1) Supremacy extends to invalidate any law which invades the essential content of any basic right;

- 2) Eternity Clause:

future amendments to the Basic Law cannot impinge upon basic principles of - Art. 1, human dignity, and

- Art. 20, federalism, democracy, republicanism, separation of powers, rule of law, popular sovereignty, social welfare state.

Basic Organization

- Bundestag: Elected legislature

- The Bundesrat

- made up of members of the executive branches of the länder

- can exercise a suspensive veto over legislation proposed by the Bundestag;

- in some cases agreement of the Bundesrat is required (for legislation to pass)

Federalism in Germany

- While most laws are made at the federal level,

- administration of most law is carried out by the länder

German Constitutional Review

- Historically, both in Holy Roman Empire and German Empire only for disputes between states and states and central government

Weimar Staatsgerichtshof

- influenced subsequent constitutional development in several respects:

- A tribunal separate from ordinary courts exercised constitutional review, taking cases as a matter of original jurisdiction and in a procedure simpler than that of an ordinary lawsuit, and

- had jurisdiction to settle disputes of a constitutional nature among and between the different levels of government.

The Basic Law: 1945-51

- German Traditions were used, rather than U.S. model

- Note that this is particularly reflected in

- their approach to federalism and

- in the social welfare democracy

- But they did accept the concept of constitutionality review

Länders Came First

- After WWII the länders were the first organized under state constitutions

- Judicial Review was permitted by these early constitutions

- But there was major debate when drafting the national constitution about what kind of court they should have at the federal level

- German judges concerned about mix of politics and law in one court

Judicial Election Proposals

- Allied states: equal number of justices elected by Bundestag and Bundesrat

- Half from federal courts and half from state courts of appeals,

Distinguished Types of Review

- Should the court be separate of part of the appellate court system?

- Should it review disputes between state organs only or citizen complaints as well?

- Two courts? One for “political” disputes between state governments and another for citizen complaints,

Note the concerns in the Compromise

- single constitutional tribunal, with authority over all constitutional disputes including the validity of laws.

- The mandatory jurisdiction of the court could be invoked only by federal and state governments, political parties and in some cases other courts;

- but the initial Basic Law, while permitting the legislature to add to the Court’s jurisdiction by statute, did not provide a constitutional right for private persons to petition the Constitutional Court, a decision influenced by practice in Weimar Germany.

Politics in 1949

- Social Democrats favored the limited access rules because political minorities would be protected

- Christian Democrats thought [broader access rules] would be useful in preserving German federalism.

- Note that the negotiations continue and matters are finally resolved not in the constitution, but in the Organic Law of the Constitutional Court

Judicial Selection

- Christian Democrats: This interest also was protected by the power of the Bundestag to choose half the judges, while the

- Social Democrats saw their interests supported by provisions that “federal judges and others” would be appointed to the court, which contemplated that persons in addition to federal judges would be appointed, thereby avoiding entrenched domination by professional judges in the largely conservative judiciary.

Constitutional Complaints

- The Constitutional Court has jurisdiction over both

- “abstract review” of laws, and over

- “concrete” review that can arise out of ordinary litigation, both of which may be invoked by government entities or officials.

Constitutional Complaints

- “concrete” review available to individuals in litigation:

- “any person who claims that a government action has violated a right under the basic law [may file] if the person has exhausted other legal remedies.”

- Created by organic act first, but constitutionalized in 1969 amendments

Individual

Concrete Norm Control

- over 95% of the Constitutional Court’s docketed caseload has been generated from constitutional complaints, which may be filed by any person who claims that a government action has violated a right under the Basic Law if the person has exhausted other legal remedies.

- Note that the constitution was amended to include this right, initially created by statute

- If the lower court refuses a reference, the individual may initiate it

Special Claims

- In 1985, Kommers reports in the first edition of his book, approximately 10,000 informal notes were received, of which 728 (or 14%) ended up being referred on to chambers, where they were all rejected; in

- 1993, 1,441 claims went to the chambers and again, all were rejected. Although the General Register office performs a “nay-saying” function, it does provide some response to each person who writes.

Effect of Decisions:

- Any decision of the Court on the constitutionality of a statute shall have the force of law, and, as law, shall be published in the Federal Gazette, along with other federal statutes.

- [Decisions] bind all organs of the government, federal and state, and all courts and public officials.

Abstract vs. Concrete Norm Control

- Abstract Norm Control: Articles 93(1)(2), at the request of the Federal government or a Land government or one third of the Bundestag members. Case does not arise out of the normal course of litigation.

- Concrete Norm Control. Article 93(1)(4a). Individual case litigation by judicial reference or by party request.

Concrete Norm Control,

- Different time limits apply for different kinds of claims.

- Although exhaustion of remedies is required, a person threatened by enforcement of a criminal statute need not violate the law in order to challenge its validity, according to Kommers.

- A constitutional complaint can only be filed by one who suffers a clear injury directly from the government action complained of.

Abstract Norm Control

- Abstract Review of Laws: The Court can be asked to decide whether a law is constitutional by a federal, or state government, or by one third of the members of the Bundestag.

- Oral argument is rare in constitutional complaint cases, but abstract review cases always have oral argument as well as written briefs.

- If the Court decides against the constitutionality of the law, it is null and void.

Concrete Norm Control: Reference System

- Concrete Judicial Review: This may be referred to as “collateral” review, and occurs during the course of ordinary litigation.

- A constitutional question of the validity of a federal or state law can be raised before ordinary German courts.

- If the court believes the law is valid, it can so decide.

- But if it believes the law is unconstitutional, it cannot so rule but must refer the question to the Federal Constitutional Court (note low number)

Separation of Powers

- Separation of Powers matters

- Balance between executive and legislative branches

- By privileged claimant only

- Political parties are given standing

Federalism Matters

- Mostly about länder enforcement of federal law

- Also deals with disputes between states

- Privileged complaint as well

Prohibiting Political Parties

- “Let’s not be Nazis … again”

- political parties that “seek to impair or do away with the free democratic basic order or threaten the existence of the Federal Republic of Germany shall be unconstitutional.”

- Basic Law Art. 21(2)

- Reserved for the federal constitutional court

Graphic: One Senate of the German Constitutional Court

Evolution of the Court

- What starts as a constitutional provision, leads to further debate on the implementation by statute

- The court itself lobbied and got reforms that guaranteed its independence and status as important organ of the governmental structure

Independence of the Court

- Budgetary independence,

- President of the Court officially 5th in governmental hierarchy,

- constitutional prohibition against limiting their powers, even in times of emergency,

- Amendments to Court Act require court approval in times of emergency.

Senate System

- The senates are separate panels of eight (originally twelve) judges of the Court that have separate jurisdiction and administrative support.

- [Plenary or en banc sessions] A “plenum” of the two senates meets to resolve jurisdictional disputes between them and to decide on rules of judicial administration.

- When justices are chosen, they are chosen for either the First or Second Senate; interchange between them is strictly limited.

First Senate

- The First Senate was given authority over concrete judicial review, involving constitutional questions that arose in ordinary litigation as well as over constitutional complaints.

- The original understanding was that it would function as a less political, more “objective” court engaged in constitutional interpretation and “judicial review.”

Senate Jurisdiction, Currie

- Now shares workload of the First Senate

- “the allocation of cases between the two [senates] is determined partly by the procedural posture of the case, partly by the substantive issues presented and partly by alphabetical order ....

- [T]he Second Senate is responsible ... for intergovernmental disputes and most abstract norm-control proceedings, for matters of criminal procedure, and for complaints filed by parties whose names begin with the letters L-Z in which questions of civil procedure predominate.“

Justices

- At least 40, both state law exams, appointed for single, nonrenewable twelve year terms

- at least three of the eight justices in each Senate must come from the federal judiciary

- justices must retire at age 68, even if this cuts short the twelve year term.

- Dissenting opinions are published

- Secret nomination process to prevent “invasion of privacy of the candidates”

Half for Bundestag & Half for Bundesrat

- Constitution allocates half to each part of parliament, Statute allocates half in each senate

- Bundesrat votes as a whole, requires 2/3 vote

- Under statute (FCCA) Bundestag uses a special Judicial Selection Committee, 8 of 12 members of the committee must vote for a justice

Judicial Qualifications

- Partisan political parity [between Christian and Social democrats],

- “religious equilibrium [principally Catholic-Protestant]… as well as some balance among Justices with centralistic (pro-central government), and those with federalistic (pro-länder) views.”

- “clean”: … untainted by Nazism,

- “wide experience in public life; … balance among Justices drawn from state justice ministries, the general civil service, and the federal courts.”

- “a portion of the seats was to be assigned to persons of Jewish ancestry.”

G. Harrold Carswell

- Referenced in the readings

- Judge in the Northern District of Florida and later in the 5th Circuit

- Nominated by Richard Nixon to replace Justice Fortas

- Criticized for favoring segregation during a political election and for his 58% reversal rate on appeal when he was a district judge!

- Voted down by the Senate 51 to 45

- Nixon the nominated Blackmun

Background of Justices

- Minimum age of 40

- Median age is 53

- Birthplace is of some importance, since it is very often related to the Justices’ religious affiliation and partisan background. Seventeen of twenty Justices born outside the Federal Republic are Protestant and, of these, eleven have been identified with the SPD and one with the FDP

Background of Justices

- Only twelve Justices have had careers confined exclusively to civil service or the judiciary.

- Twenty-eight have held high civil service positions in state or national government.

- Ten have had legislative experience.

- Nine Justices spent most of their professional lives practicing law.

- Five had careers as professors of law, while three others held professorships at one time or another.

US Const. Art. III, Sec. 1

- The judicial Power of the United States, shall be vested in one supreme Court, and in such inferior Courts as the Congress may from time to time ordain and establish. The Judges, both of the supreme and inferior Courts, shall hold their Offices during good Behavior, and shall, at stated Times, receive for their Services, a Compensation, which shall not be diminished during their Continuance in Office.

U.S. Const. Art. III,

Sec. 2, Clause 1.

- The judicial Power [of the United States] shall extend to [i] all Cases, in Law and Equity, arising under this Constitution, the Laws of the United States, and Treaties made, or which shall be made, under their Authority; [ii] to all Cases affecting Ambassadors, other public Ministers or Consuls; [iii] --to all Cases of admiralty and maritime Jurisdiction; [iv] --to Controversies to which the United States shall be a Party; ***

Art. III, Sec. 2, Cl. 1 cont.

- The judicial Power [of the United States] shall extend to *** [v] --to Controversies between two or more States; [vi] --between a State and Citizens of Another State; [vii] between Citizens of different States; [viii] --between Citizens of the same State claiming Lands under Grants of different States, and [ix] between a State, or the Citizens thereof, and foreign States, Citizens or Subjects.

US Const. Art. III, Sec. 2, Cl 2.

- Jurisdiction of Supreme Court

In all Cases affecting Ambassadors, other public Ministers and Consuls, and those in which a State shall be Party, the supreme Court shall have original Jurisdiction. In all the other Cases before mentioned, the supreme Court shall have appellate Jurisdiction, both as to Law and Fact, with such Exceptions, and under such Regulations as the Congress shall make.

US Const. Art. VI, Cl 2. Supremacy.

- This Constitution, and the Laws of the United States which shall be made in Pursuance thereof; and all Treaties made, or which shall be made, under the Authority of the United States, shall be the supreme Law of the Land; and the Judges in every State shall be bound thereby, any Thing in the Constitution or Laws of any State to the Contrary notwithstanding.

Deshaney v. Winnebago County,

US Supreme Court (1989)

- There is] nothing in the language of the Due Process Clause [that] requires the State to protect the life, liberty, and property of its citizens against invasion by private actors. The Clause is phrased as a limitation on the State’s power to act, not as a guarantee of certain minimal levels of safety and security. … [Its] language cannot fairly be extended to impose an affirmative obligation on the State to ensure that those interests do not come to harm through other means.

Religion: Church and State

- Neutrality as to religion.

- In the US it means toleration and no public support, for the most part.

- In Germany, Toleration, encouragement and and at least some support.

Religion: Church and State

- In Germany students get educated in religion in public schools if they are Christian or Jewish. Muslims take ethics. In fact, non-religious persons, or persons who from religions other than Christianity or Judaism have only ethics available.

Civil rights cases in 1883

- The U.S. Supreme court individual invasion of individual rights was not subject to CONSTITUTIONAL protection.

- Thus private discrimination in jobs, housing and services are not a constitutional matter.

- However, STATUTORY protection was given, mostly based on the commerce clause.

Map: Europe Today

H. Constitutional Courts and Constitutional Adjudication, Major Cases: Germany

-

You should refer to the text of the German Constitution, which you will find here:

[Click here] -

Visit the English Language site of the German Federal Constitutional Court.

[Click here] -

For a primer on German political parties, visit the BBC website.

[Click here] -

For a view from Germany, visit the Spiegel Online site.

[Click here]

- 3. German Constitutional “Foundational” Cases?

- “Legitimacy” of the Court

- Whether particular case decisions, or a series of decisions, may play a role in building legitimacy for constitutional courts.

- “Foundational” Decisions

- Whether there are “foundational” cases in other functioning systems of constitutional judicial review and what makes a case appear “foundational” within its system

- “Legitimacy” of the Court

- Compare U.S. Caselaw

- Marbury v. Madison (1803)

- Judicial Review Binding on other Branches

- Marbury v. Madison (1803)

- McCulloch v. Maryland (1819)

- Implied Federal Legislative Powers

- Marbury v. Madison

- Judicial Review Implicit

- The Basis for Judicial Review review [is] implicit in the nature of a written constitution, in the supremacy clause and in Article III’s grant of judicial power.

- Chief Justice John Marshall reasoned as follows.

- First, the Constitution is law and must be followed; indeed, the supremacy clause makes the Constitution the supreme law of the land.

- Second, the judges of the judicial branch, being vested by Article III with the "judicial Power of the United States," have the power to say what the law is in cases that come before them.

- It follows then that judges, in deciding an issue to which both a statute and the Constitution apply, must follow the hierarchy of law set out in the supremacy clause: they must apply the constitutional provision and disregard the statute.

- Judicial Review Implicit

- McCulloch v. Maryland

- The issue: Bank of the United States

- in McCulloch was the constitutionality of Congress’s establishment of a Bank of the United States.

- No Express Congressional Authority

- But he held that the grant of explicit enumerated powers necessarily implied other powers to do what Congress believed appropriate to carry out those enumerated powers.

- “Implied Authority”

- Thus, because Congress had explicit power to lay and collect taxes, to borrow money, to regulate commerce and to raise armies-and a bank would clearly assist legislative programs enacted pursuant to these powers —Congress had the implied power to create a bank. In reaching this result, Marshall found support in the “necessary and proper” clause, the last of the enumerated powers, giving Congress the power “[t]o make all Laws which shall be necessary and proper for carrying into Execution the foregoing Powers.”

- German CC and the Southwest Case

- Its very first case

- Ruling