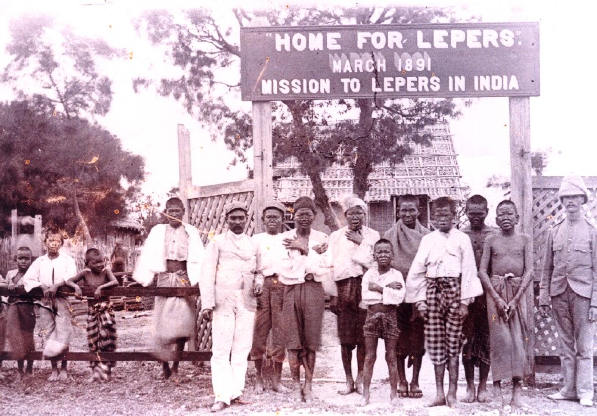

Leper Hospitals and Colonies

Source:

http://www.leprosyhistory.org/graphics/gallery/burma2.jpg

In the Middle Ages we begin to see a rise

in a transition from simply leper colonies to leper hospitals, and churches

were beginning to open their doors to the treatment of lepers. Hospitals such

as the St. James leper hospital in Chichester opened in 1118 by Queen Maud (a

consort of Henry I), and the Hospital of St. Nicholas Harbledown opened in

1084, embodied the ideas in medieval religious society that it was a noble

thing to be able to converse and build relationships with the leper. Indeed,

institutions such as those at Harbledown were run by monastics, and lepers were

encouraged to live monastic life styles in these establishments, for their

health as well as quarantine, but also because the suffering of a leper was

viewed as Purgatory on earth, and therefore more holy than a normal personŐs

suffering.

The only leper hospital in the continental

United States was established between New Orleans and Baton Rouge in 1894 in

Carville, Louisiana. The center at Carville was at first much like a prison

where leprosy sufferers were sent for isolation in the early 20th

century. Many patients were entered at the site under false names and few gave

even such information as their hometowns

for fear of the shame that even revealing that much information would

bring on their families and communities. The hospital transitioned in later

years into less of a prison-like institution to a place of treatment and

therapy, but the stigma remained. Patients isolated at Carville developed their

own subculture, writing their own newspaper and even having their own Mardi

Gras celebration. A study of former patients at the Carville hospital in 1990

shows that some of these patients had conducted elaborate lies to tell the

everyday person about their illness. Instead of admitting the disease, one

patient interviewed had claimed injuries to his hand as well as his feet were

due to his involvement in the conflict in Korea. His hands were deformed

because of a faulty grenade, he claimed. This story was easy to believe, and

easy to claim as the hospital at Carville was a United States Public Health Service

hospital and admitted many veterans after World War II. The man even said that

after he admitted to people that his deformities were, in fact, due to leprosy,

people refused to believe him. People would rather believe that leprosy was a

disease of the past, and not of

our modern society. The Hospital at Carville was shut down in 1999.

Leper colonies also existed in Hawaii in

the mid-19th century, exiled to the Kalaupapa Peninsula. This

isolation of leper sufferers remained until 1969 when the quarantine policy was lifted because the disease was discovered

treatable at outpatient facilities. Because of so deep rooted a stigma, many disease sufferers decided

to stay in the quarantined area.

Leper colonies still exist today. In 2001,

a colony in Japan was scrutinized for possible mistreatment of disease

sufferers, keeping them quarantined until 1996, well after the disease was

found to be not highly contagious. The 1907 Leprosy Prevention Law forced

people affected by leprosy onto the islands off of Japan, including the island

of Oshima. The Japanese government forcibly kept those with the disease on the island,

as well as in many cases, forcibly aborted babies when those affected with

leprosy became pregnant. An estimate suggests over 3,500 abortions were carried

out, even though leprosy is not genetic. According to a New York Times Article,

in June 2001 the Japanese government said it would not contest a court ruling

that ordered it to pay $15 million to 127 plaintiffs who had challenged the law

that kept patients confined to sanitariums on distant mountains and small

islands like Oshima. The government issued a formal apology, and promised to

provide all patients with compensation, and aid to return to society.

| Home | What | Art & Lit | Hospitals & Colonies | Today | References|