Treponema pallidum subspecies pallidum

The

endemic treponematoses are currently estimated to affect at least 2.5

million people worldwide.

I. The Bacteria

II. Differences from venereal syphilis

III. Theories on origins and evolution of Treponema

IV. The Diseases

A. Yaws

B. Bejel

C. Pinta

V. Effects on Bone

A. Skull

B. Long Bones

VI. Diagnostic tests

VII. Treatment

VIII. Eradication

IX. Works Cited

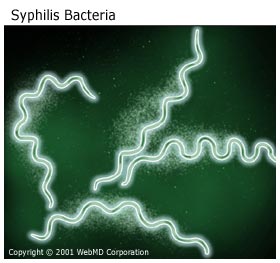

THE BACTERIA*

T. carateum (pinta)

T. pallidum pertenue (yaws)

T. pallidum endemicum (bejel)

THEORIES ON THE ORIGINS OF Treponema

In the hot, humid climate of Sub-Saharan Africa, treponematosis originated from nonhuman primates as a childhood disease (yaws) transmitted by skin-skin contact. The bacteria evolved alongside humans in migrating hunter-gatherer populations throughout the Paleolithic. Eventually, groups moved into drier climates, and the ancestral treponeme common to apes and man retreated to moister areas of the body (manifested as endemic syphilis, or bejel).

Populations crossing the Bering Strait into the New World from Asia carried the endemic syphilis, and mutations accumulated until the bacteria evolved into contemporary pinta and bejel. Eventually, the climatic change in the New World caused a shift back to yaws, and the crowded, unsanitary conditions in the Americas during the Neolithic facilitated the spread through increased child-child contact.

Meanwhile, in the Old World in 4000 B.C., urbanization improved community hygiene, and sexual contact was the only way to permit transmission of treponemas, as promiscuity and prostitution increased the spread of the disease.

Order: Spirochaetales

Family: Spirochaetacaeae

genus: Treponema

Family: Spirochaetacaeae

genus: Treponema

T. pallidum pertenue (yaws)

T. pallidum endemicum (bejel)

- Morphologically identical, cannot be distinguished by any known test

- All have similar effects, differing in degree and range of affected tissues

- May be genetically distinct, lack cross-immunity (so

have antigenic differences)

- TRANSMISSION: skin and mucous membrane contact or sharing eating utensils

- DISTRIBUTION: Closely related to poverty and isolation from organized social and health services (predominant in underprivileged remote rural communities)

- Unlike venereal syphilis, central nervous system

involvement and congenital transmission do not occur in the endemic

infections, usually limited to skin, bone, cartilage, and mucosae

- Usually affect children under 15 years

THEORIES ON THE ORIGINS OF Treponema

1) Pre-Columbian hypothesis:

Origins in

the Old World

This explanation proposes that syphilis was present in Europe before

Columbus' voyage, but was not identified as a separate

disease from leprosy before the 1490s. According to this theory,

populations were small, and treponemal infection was mild and chronic.

Larger population sizes selected for more acute infections, and the

types of treponemes that depended on direct skin contact were

outcompeted by the hardier, sexually transmitted strain. Thus,

the origin of venereal syphilis resulted from social and economic

events, and not directly related to the return of Columbus from the New

World. Proponents of this theory point to the ancient and medieval

sources showing Pre-Columbian treponema

infections in Europe.2) Columbian hypothesis: Origins

in the New World

One hypothesis argues for a New World origin, and holds that sailors

who accompanied Columbus and other explorers brought the disease back

to Europe in 1493. These researchers believe that syphilis originated

in the

New World due to a mutation in the bacteria that causes yaws

(Rothschild, 2000). Based on a study of 1,000 skeletons from Africa,

the Middle East, Europe, and Asia, Rothschild found no evidence of

pre-Columbian Old World syphilis. According to his theory, Columbus'

crew contracted syphilis in the New World and spread it through

Europe.

The following syphilis endemic of 1500 suggested that the European

population was previously unexposed to the disease which rapidly spread

once introduced. Furthermore, the Rothschilds found that the earliest

yaws cases in the New World collections were at least 6,000 years old,

while the first syphilis cases were 800-1,600 years old. This suggests

that syphilis may be a New World mutation of yaws, which has a

worldwide distribution. The discovery of treponemal antigens in

the remains of a Pleistocene bear in the Americas, as well as an

abundance of skeletal material with lesions that suggest treponemal

agents, lend strong support for the presence of the disease in the New

World pre-1492.3) Unitarian hypothesis

Treponema agent was present in the New World and the Old World at the

time of Columbus' voyage, and has evolved along with human populations.

This theory assumes that the

treponematoses may have come

down from a nonhuman primate ancestor, and the infections have exisited

in

man and his primate ancestors for millions of years (Cockburn,

1977). According to this theory, each of the above mentioned

trepanematoses are just manifestations of one single disease occuring

with different social and environmental factors. In the hot, humid climate of Sub-Saharan Africa, treponematosis originated from nonhuman primates as a childhood disease (yaws) transmitted by skin-skin contact. The bacteria evolved alongside humans in migrating hunter-gatherer populations throughout the Paleolithic. Eventually, groups moved into drier climates, and the ancestral treponeme common to apes and man retreated to moister areas of the body (manifested as endemic syphilis, or bejel).

Populations crossing the Bering Strait into the New World from Asia carried the endemic syphilis, and mutations accumulated until the bacteria evolved into contemporary pinta and bejel. Eventually, the climatic change in the New World caused a shift back to yaws, and the crowded, unsanitary conditions in the Americas during the Neolithic facilitated the spread through increased child-child contact.

Meanwhile, in the Old World in 4000 B.C., urbanization improved community hygiene, and sexual contact was the only way to permit transmission of treponemas, as promiscuity and prostitution increased the spread of the disease.

NO CLEAR RESOLUTION

Unfortunately, it is difficult to definitively pinpoint the origin of

syphilis, because skeletal evidence must be proven to be both ancient and syphilitic. However, an

exhaustive review of the documentary and skeletal evidence of

treponematosis by Baker and Armelagos conclude that nonvenereal

treponemal infection is a New World disease that spread to the Old

World and became a venereal disease following European contact.THE

DISEASES

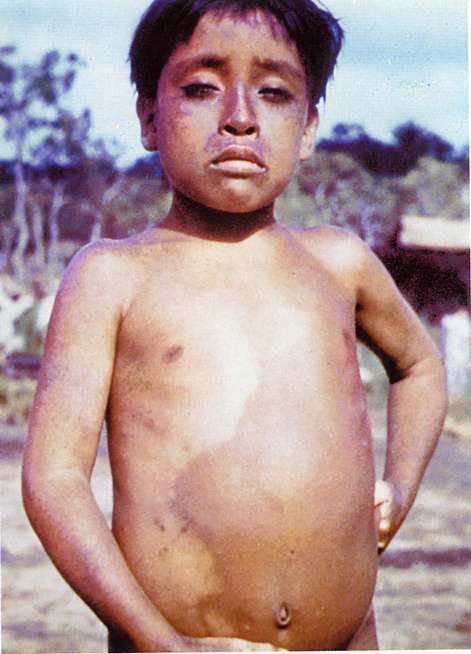

SYMPTOMS OF YAWS

- Papule that scars, infection in the bloodstream

- Cutaneous lesions: macules, papules, nodules.

- Lympadenitis with swollen tender lymph nodes.

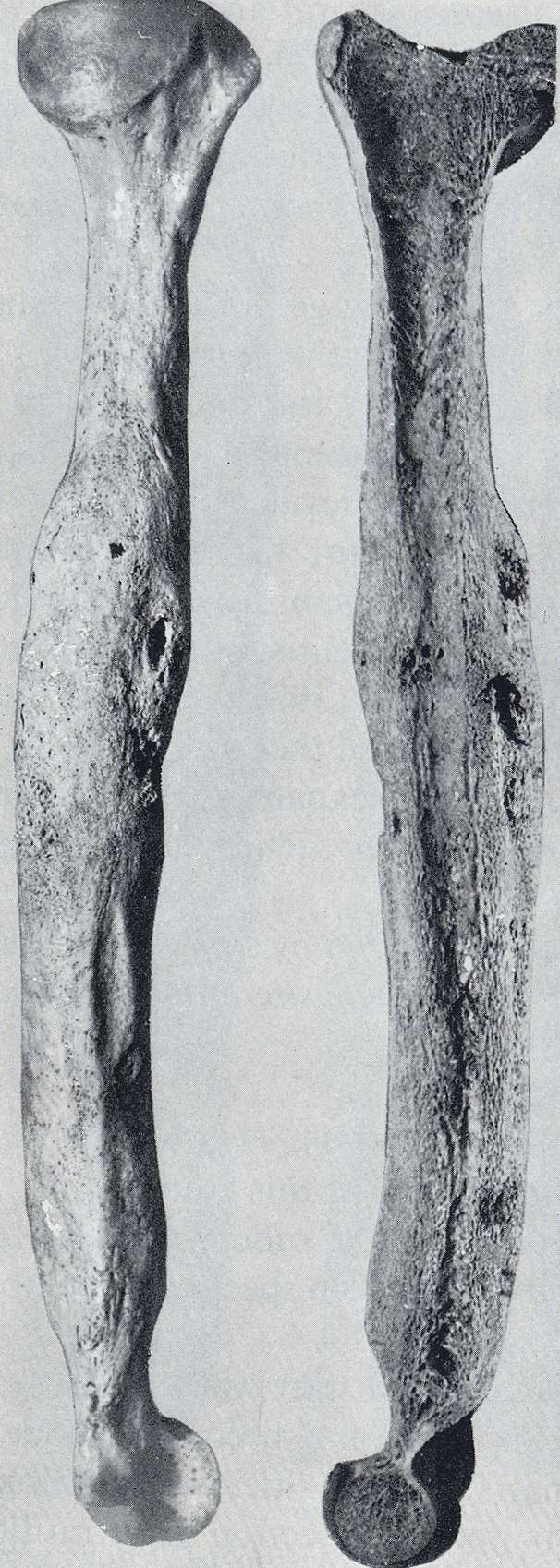

- Late stage: periosteal infection,

osteoperiostitis of forearm or leg, polydactylitis of the hand or foot,

deformities including sabre tibia (curvature of the tibia) and

gangosa in the nose (results of destructive ulceration of the palate

and nasal septum--can be seen in skeletal remains),

juxta-articular nodules

sabre tibia

- hyperkeratoses of the palms and soles and gummas of the skull

hyperkeratotic macular plantar early yaws

DISTRIBUTION OF YAWS

- Rural populations in the rain forest areas with high levels of humidity and rainfall

SYMPTOMS OF BEJEL

- primary lesions: painless, white mucinous ulcers

in the

oral cavity and the nipples of breastfeeding women

- secondary lesions: split pauples or rashes

- Periostitis of long bones or hand, sabre tibia,

juxta-articular nodules

- Late stage: Infection of the eye: uveitis, optic atrophy, chorioretinitis; Gangosa causes destruction of the nasopharyngael cartilage

gangosa

- Dry, hot and temperate climates, endemic in rural and semi-urban communities living in low hygienic conditions, including: Russia, the Near East, eastern Mediterranean, southern Africa, and the nomadic and semi-nomadic rural populations in northern Africa

SYMPTOMS

- Slowly enlarging copper-colored or blue papules, with smaller satellite lesions

- Seconardary lesions: small papules greyish, light-blue, or pale-mauve pigmentation (often mottled)

- Late stage: deeper tissue and organ infection, enlargement of the regional lymph nodes.

DISTRIBUTION/EPIDEMIOLOGY

- Common in young adults

- Caribbean, Central and South America, humid climates

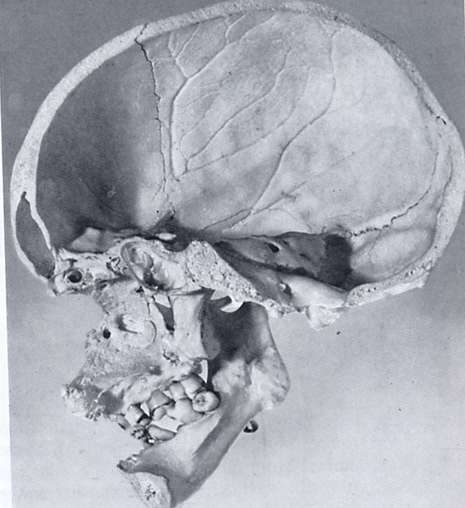

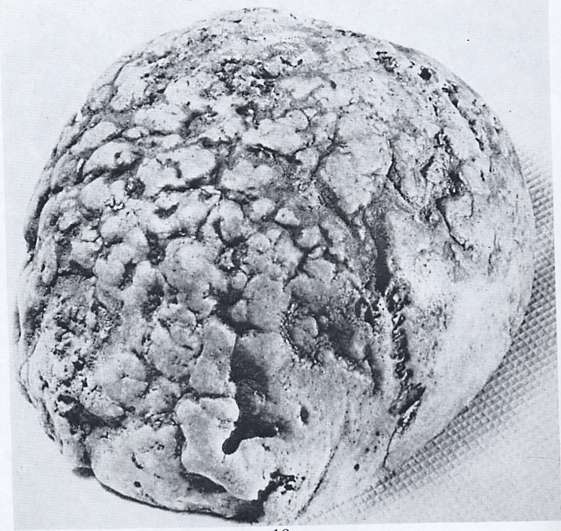

Sequence of bone destruction of syphilis in the crania (caries sicca)

EVIDENCE IN THE SKULL

naso-palatine destruction

Caries sicca in syphilis

EVIDENCE IN THE LONG BONES

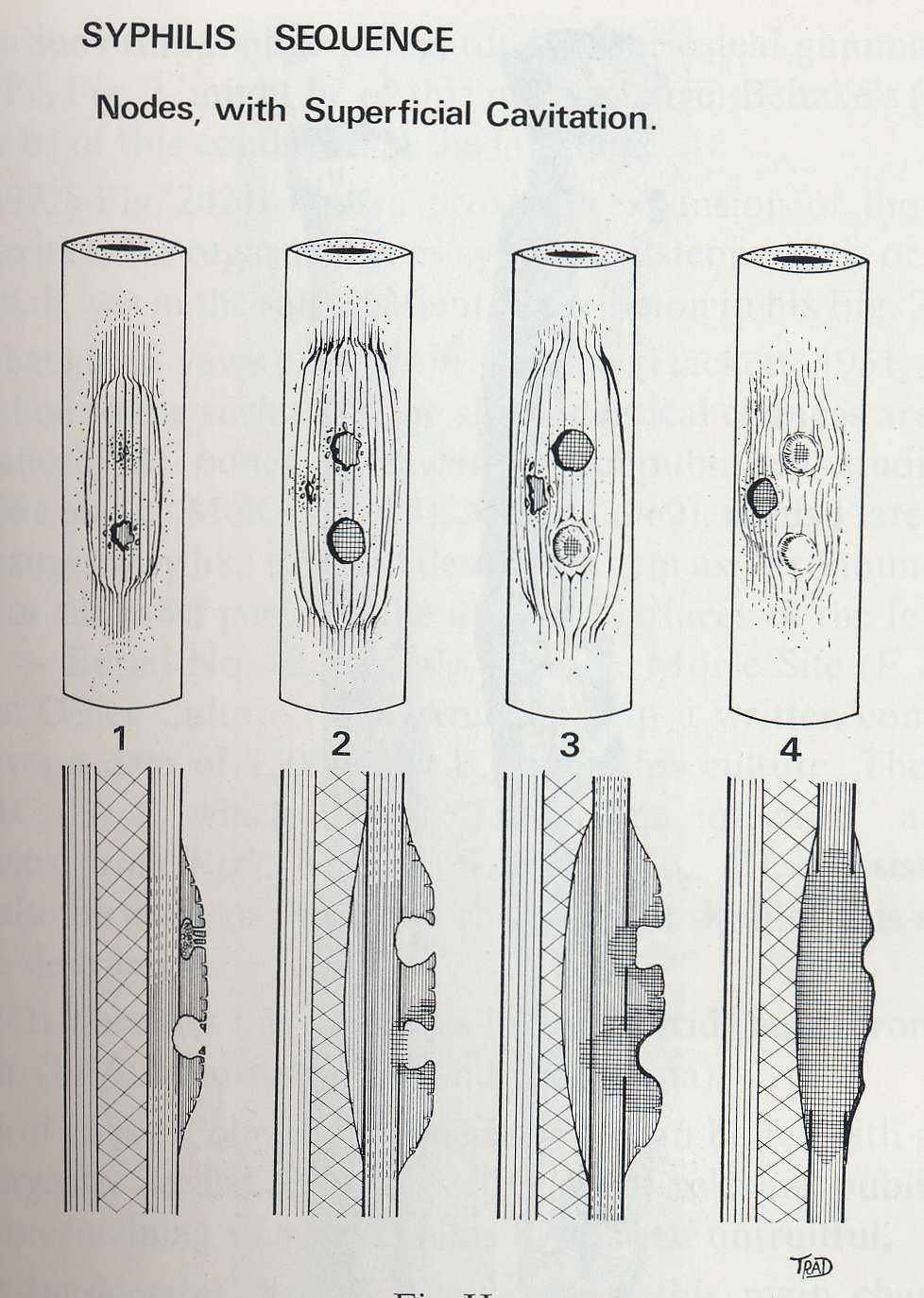

Development of nodes in the long bone

Nodes/expansion with superficial cavitation

- Dark-field microscopy from lesion fluids

- Direct fluorescent antibody (DFA) test: detects T. pallidum on a slide

- Agglutination assays for antibodies to T. pallidum

- *No test can distinguish between

different treponematoses or from venereal syphilis

TREATMENT

- Single does antibiotic with benzathine penicillin (or tetracycline, doxycycline, erythromycin)

1) Screening

2) Adequate diagnoses of infected patients

3) Health education of the population

4) Improved hygiene

Ackerknecht, E. H. (1977) Paloepathology. In (D. Landym ed.) Culture, Disease, and healing: Studies inMedical Anthropology. New York: Macmillan, 71-77.

Antal, G. M., S. A. Lukehart, and A. Z. Meheus. (2002) The Endemic treponematoses. Microbes and Infection. 4: 83-94.

Baker, B. J. and G. J. Armelagos. (1988) The Origin and Antiquity of Syphilis: Paleopathological Diagnosis and Interpretation. Current Anthropology. 29: 703-737.

Cockburn, T. A. (1977) Infectious diseases in ancient populations. In (D. Landy, ed.) Culture, Disease, and Healing: Studies in Medical Anthropology. New York: Macmillan, 83-95.

Fine, S. and L. S. Fine. Treponematosis (Endemic Syphilis). Retrieved from eMedicine. 20 November 2004. http://www.emedicine.com/med/topic2305.htm.

Hackett, C. J. (1976) Diagnostic Criteria of Syphilis, Yaws, and Treponarid (Treponematoses) and of Some Other Diseases in Dry Bones (for Use in Osteo-Archaeology). Berlin: Springer-Verlag.

Jankauskas, R. and S. Saul. (1989) Discussion and Criticism: On the Origin and Antiquity of Syphilis. Current Anthropology. 30: 481-482.

Oriel, J. D. and A. Cockburn. (1974) Syphilis: where did it come from? Paleopathological Newsletter. 6: 9-12.

Perine, P.L., D. R. Hopkins, P. L. A. Niemel, R. K. St. John, G. Causse, and G. M. Antal (1984) Handbook of Endemic Treponematoses. Geneva: World Health Organization.

Rose, M. (1997) The Origins of Syphilis. Archaeology: a publication of the Archaeological Institute of America. 50.

Rothschild, B. M., L. C. Fernando, A. Coppa, and C. Rothschild. (2000) First European Exposure to Syphilis: The Dominican Republic at the Time of Columbian Contact. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 31:936-941