Paleopathological Evidence

Paleopathological Evidence

Although

abundant documentary evidence for smallpox in antiquity exists, physical

evidence is scant. The most striking

indication of the disease is found in mummies.

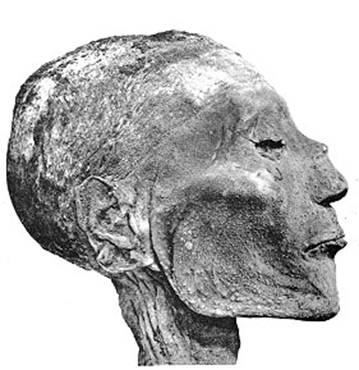

The mummy of Egyptian Pharaoh Ramses V, who was in his early thirties

when he died in 1157 B.C., exhibited a pustular rash on the face, neck,

shoulders and arms. Donald Hopkins, a

physician and epidemiologist who was permitted to partially examine this mummy

in 1979, describes a “rash of elevated ‘pustules,’ each about two to four

millimeters in diameter...pale yellow against a dark brown-reddish background”

(1983, 15). The image of the pharaoh’s face, covered in pustular-looking

lesions, can be found in much of the literature addressing the history of

smallpox.

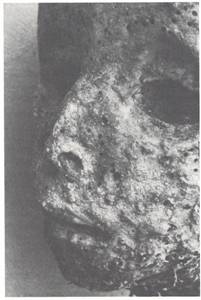

At least one attempt

to positively identify smallpox in mummies, however, was successful. Fornaciari and Marchetti (1986), utilizing an

immunological assay, were able to identify smallpox as the agent responsible for

the pustular lesions on a sixteenth century child’s mummy from

At least one attempt

to positively identify smallpox in mummies, however, was successful. Fornaciari and Marchetti (1986), utilizing an

immunological assay, were able to identify smallpox as the agent responsible for

the pustular lesions on a sixteenth century child’s mummy from

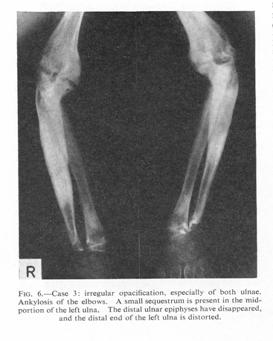

Skeletal evidence of smallpox in antiquity,

however, is not so apparent. Although,

as mentioned previously, joint lesions can occur in smallpox infections, it is

possible that in skeletal remains it would be difficult to differentiate such

pathology from other degenerative joint diseases. Cohen (1989, 108), in discussing skeletal

evidence in prehistoric remains for various infectious diseases, asserts that

identification of smallpox is controversial, but that it “may be identifiable

from patterns of inflammation on the ulna.”

Evidence in modern

populations is more apparent, and a pattern is clear. Eekels et al. (1964) reported three cases of

osteomyelitis variolosa seen during a smallpox epidemic that occurred in the Republic

of the

Evidence in modern

populations is more apparent, and a pattern is clear. Eekels et al. (1964) reported three cases of

osteomyelitis variolosa seen during a smallpox epidemic that occurred in the Republic

of the

Ortner and Putschar (1981, 228) report

similar findings from work done in