PREVENTION

In the past

Smallpox

is the first disease for which control by immunization was developed.  Efforts to

control it began in antiquity. In

Efforts to

control it began in antiquity. In  in

in

Variolation was

met with mixed reviews everywhere it was used; it was effective in some, but  there are many

reports of patients dying of smallpox introduced by variolation, and of

epidemics resulting (Radetsky, 1999). In

1796, Edward Jenner, an English country physician, changed all that. Based on observations that people who milked

cows and contracted cowpox were immune to smallpox, he inoculated a boy with

fluid from a cowpox lesion on a milkmaid’s hand. Two months later, after inoculation with

smallpox fluid, the boy developed no signs of smallpox. Oddly, although Jenner was praised by many

for his pioneering work, he had fierce critics.

Furthermore,

there are many

reports of patients dying of smallpox introduced by variolation, and of

epidemics resulting (Radetsky, 1999). In

1796, Edward Jenner, an English country physician, changed all that. Based on observations that people who milked

cows and contracted cowpox were immune to smallpox, he inoculated a boy with

fluid from a cowpox lesion on a milkmaid’s hand. Two months later, after inoculation with

smallpox fluid, the boy developed no signs of smallpox. Oddly, although Jenner was praised by many

for his pioneering work, he had fierce critics.

Furthermore,  there is some

question as to whether Jenner’s vaccine was actually cowpox; the material he

used initially may have come from horsepox, to which both horses and cows were

susceptible. Nevertheless, cowpox

vaccination gradually became widely accepted and made great inroads in the

coming years towards preventing smallpox.

there is some

question as to whether Jenner’s vaccine was actually cowpox; the material he

used initially may have come from horsepox, to which both horses and cows were

susceptible. Nevertheless, cowpox

vaccination gradually became widely accepted and made great inroads in the

coming years towards preventing smallpox.

Current vaccine

The

vaccine available today is made from live vaccinia virus, which, like variola,

is an  orthopoxvirus;

its use emerged sometime during the 19th century. It is not the cowpox virus Jenner used, and

the circumstances of why and when the vaccination changed are unknown (Fenner

et al., 1988, 278).

orthopoxvirus;

its use emerged sometime during the 19th century. It is not the cowpox virus Jenner used, and

the circumstances of why and when the vaccination changed are unknown (Fenner

et al., 1988, 278).

The Centers for

Disease Control and Prevention (CDC, http://www.cdc.gov/smallpox)

report that historically the modern vaccine has been 95% effective in

protecting people who are vaccinated, and that those receiving the vaccine are

highly immune to the disease for three to five years. After that, immunity steadily decreases, and

protection is questionable after about ten years. Revaccination can extend immunity. Furthermore, although there is no cure for

smallpox, vaccination can prevent or reduce severity of the disease if a person

exposed to the virus is vaccinated within four days of exposure and prior to

the appearance of the rash.

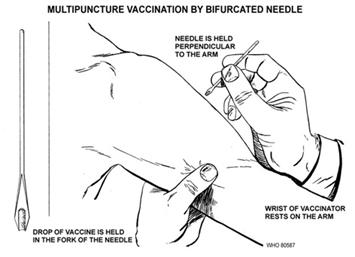

Administration of the vaccine involves

applying the live virus into the skin with a bifurcated needle that is dipped

into the solution containing the vaccinia.

The skin –typically in the upper arm – is pricked from 15 to 20 times,

just enough to draw a small amount of blood.

The shallow punctures are concentrated into an area of about one square

centimeter. According to the CDC, after

three or four days, if the vaccination “takes,”

Administration of the vaccine involves

applying the live virus into the skin with a bifurcated needle that is dipped

into the solution containing the vaccinia.

The skin –typically in the upper arm – is pricked from 15 to 20 times,

just enough to draw a small amount of blood.

The shallow punctures are concentrated into an area of about one square

centimeter. According to the CDC, after

three or four days, if the vaccination “takes,”  a red, itchy

bump appears which fills with pus and starts to drain, generally at the end of

the first week. During the second week

the lesion dries and scabs over. After

about three weeks the scab falls off, but until that time, since live virus is

administered, the infection can be spread to others if the vaccination site is

not protected. Those who have never

received the vaccine generally have a more severe reaction than people who have

been vaccinated previously.

a red, itchy

bump appears which fills with pus and starts to drain, generally at the end of

the first week. During the second week

the lesion dries and scabs over. After

about three weeks the scab falls off, but until that time, since live virus is

administered, the infection can be spread to others if the vaccination site is

not protected. Those who have never

received the vaccine generally have a more severe reaction than people who have

been vaccinated previously.

Some

complications are associated with vaccination.

Besides the

typical mild side effects of sore arm, body aches and fever in some cases,

several serious complications can develop.

In fact, the vaccine is contraindicated in people who are immunosuppressed

or have eczema, pregnant or breast feeding women, and children less than one

year of age. When complications do

occur, the WHO reports the following (out of 14 million vaccinations

administered): eczema vaccinatum in

people who have eczema (74 cases, no deaths); vaccinia necrosum (progressive

vaccinia), typically in immmunosuppressed patients, in which the vaccination

lesion progresses and does not heal (11 cases, four deaths); generalized

vaccinia, a rash in healthy individuals (143 cases, no deaths); and

postvaccinial encephalitis, the most serious complication which can result in

paralysis, cerebral impairment, and death in 25% to 35% of cases. Additionally, Esposito and Fenner (2001)

report ocular vaccinia which can result in permanent visual defects.

Besides the

typical mild side effects of sore arm, body aches and fever in some cases,

several serious complications can develop.

In fact, the vaccine is contraindicated in people who are immunosuppressed

or have eczema, pregnant or breast feeding women, and children less than one

year of age. When complications do

occur, the WHO reports the following (out of 14 million vaccinations

administered): eczema vaccinatum in

people who have eczema (74 cases, no deaths); vaccinia necrosum (progressive

vaccinia), typically in immmunosuppressed patients, in which the vaccination

lesion progresses and does not heal (11 cases, four deaths); generalized

vaccinia, a rash in healthy individuals (143 cases, no deaths); and

postvaccinial encephalitis, the most serious complication which can result in

paralysis, cerebral impairment, and death in 25% to 35% of cases. Additionally, Esposito and Fenner (2001)

report ocular vaccinia which can result in permanent visual defects.