ETIOLOGY AND EPIDEMIOLOGY

By the end of

the 18th century, smallpox had a worldwide distribution, and as

recently as 1967, it killed one in four of those infected (World Health Organization

[WHO, http://www.who.int/emc/diseases/smallpox/factsheet.html]). With the exception of those who have been

vaccinated or previously survived the disease, everyone is susceptible if

exposed; mortality is highest in the very young and the elderly.

There are two

major forms of smallpox, which differ in their  severity. Variola major, the more common (90% of all cases) and

serious of the two, has a fatality rate of approximately 30%, while less than

1% of the victims of variola minor succumb to the

disease. Two additional forms are

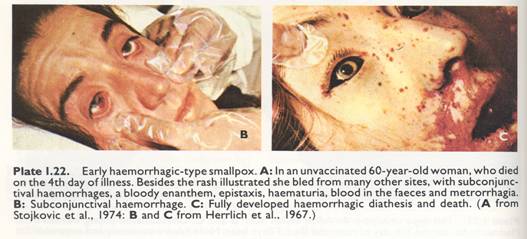

known. Hemorrhagic smallpox, which

occurs primarily in adults, results in a rash and hemorrhaging into the skin,

mucous membranes and the base of the pox lesions. Malignant smallpox, also known as flat

smallpox, occurs in 5% to 10% of patients, and is characterized by soft, flat

lesions with a buried appearance. These

two latter forms of the disease, although rare, are nearly always fatal.

severity. Variola major, the more common (90% of all cases) and

serious of the two, has a fatality rate of approximately 30%, while less than

1% of the victims of variola minor succumb to the

disease. Two additional forms are

known. Hemorrhagic smallpox, which

occurs primarily in adults, results in a rash and hemorrhaging into the skin,

mucous membranes and the base of the pox lesions. Malignant smallpox, also known as flat

smallpox, occurs in 5% to 10% of patients, and is characterized by soft, flat

lesions with a buried appearance. These

two latter forms of the disease, although rare, are nearly always fatal.

Transmission

of the virus is primarily through the respiratory route; infected air droplets

are spread during face-to-face contact with an infected person. However, direct contact with bodily fluids

and fomites, dust from contaminated clothing and

bedding, can also transmit the disease.

Although patients are most contagious early in the course of the

disease, smallpox can be transmitted until after the lesions scab over and the

last scab falls off.