Vioxx

by

Breckon

Pav

Dr.

Bradley

December 5, 2002

History

The selective COX-2 inhibitor Vioxx (rofecoxib) has a relatively short

history on the public market. It

was presented for FDA approval in 1998 by Merck Pharmaceuticals as an

alternative to the traditional pain relievers, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory

drugs (NSAIDs) like Tylenol, Advil, and ibuprofen.

Vioxx was reviewed and approved in 1999 as an effective treatment of

osteoarthritis, menstrual pain (dysmenorrhea), and severe pain in adults (Miceli

1).

Since then, Vioxx has undergone further studies concerning its effects on

the formation of gastrointestinal ulcers and its cardiovascular threats.

Package inserts have changed for better and for worse through the few

years of Vioxx’s popularity. However,

the bottom line is that rofecoxib offers powerful pain relief without the

typical NSAID risk of GI tract infection and ulcers.

Chemical Properties

Rofecoxib has a molecular weight of 314.36 amu, a structure of C17H14O4S,

and is chemically labeled “4-[4-(methylsulfonyl)phenyl]-3-phenyl-2(5H)-furanone.”

The pill color ranges from white to yellowish.

Inactive ingredients in Vioxx are croscarmellose sodium, hydroxypropyl

cellulose, lactose, magnesium stearate, microcrystalline cellulose, yellow

ferric oxide, and red ferric oxide (in 50 mg pills); oral suspensions include citric acid monohydrate (·H2O), sodium citrate dihydrate (·2H2O), sorbitol solution, strawberry flavor, xanthum gum, purified water,

sodium methylparaben (0.13% as preservative), and sodium propylparaben (0.02% as

preservative) (Description 1).

The

Solubility of Rofecoxib

|

Water

|

Acetone

|

Methanol/Isopropyl

Acetate

|

Ethanol

|

Octanol

|

|

Insoluble

|

Slightly

soluble

|

Slightly

soluble

|

Very

slightly soluble

|

Insoluble

|

Rofecoxib falls into a

category of NSAID drugs called COX-2 inhibitors. To understand the nature and mechanisms of Vioxx, it is

necessary to first examine this enzyme and its functions.

Cyclooxygenase

The enzyme

cyclooxygenase (COX) was first isolated in 1979, but it was later discovered

that COX existed in two forms: COX-1

and COX-2 (Bridges 1). COX enzymes

(also called prostaglandin endoperoxide synthase enzymes) aid in the synthesis

of prostaglandins (PGs), a type of fatty acids associated with smooth muscle

contraction. Prostaglandins, when

existing in a certain isoform (H2), can cause irritation to an

inflammation site. The synthesis of

these undesirable prostanoids (prostaglandins, thromboxanes, and others) occurs

in the cell membrane, and is catalyzed by COX-2. COX-2 enzymes congregate at inflamed sites, intensifying the

painful effect by producing PGs. It

was therefore concluded that shutting down the enzyme pathway (COX) used to

create PGs could reduce and even eliminate their effect on inflamed areas.

The two

COX enzymes exist in different concentrations throughout an organism. At inflammation sites, COX-2 is much more abundant.

Since COX-1 helps produce prostaglandins that protect the stomach lining,

it is present in larger quantities in the GI tract.

Because typical NSAIDs are not selective when targeting enzymes, they end

up shutting down prostaglandin synthesis everywhere in the body.

This results in a greater risk of GI tract infection and ulceration,

inciting research to develop a drug that inhibits only COX-2, the more

pro-inflammatory of the two enzymes.

The two

COX enzymes exist in different concentrations throughout an organism. At inflammation sites, COX-2 is much more abundant.

Since COX-1 helps produce prostaglandins that protect the stomach lining,

it is present in larger quantities in the GI tract.

Because typical NSAIDs are not selective when targeting enzymes, they end

up shutting down prostaglandin synthesis everywhere in the body.

This results in a greater risk of GI tract infection and ulceration,

inciting research to develop a drug that inhibits only COX-2, the more

pro-inflammatory of the two enzymes.

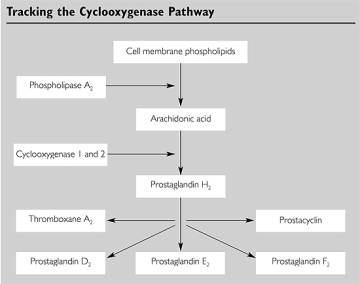

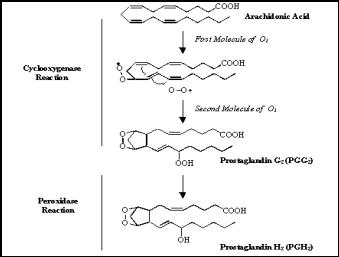

As

shown in Figure 1, both COX enzymes catalyze a critical step in similar

reactions: Converting free membrane arachidonic acid to a prostaglandin.

External physiologic stimuli (e.g. tissue damage) can activate

phospholipase A2, which cuts arachidonic acid from the membrane

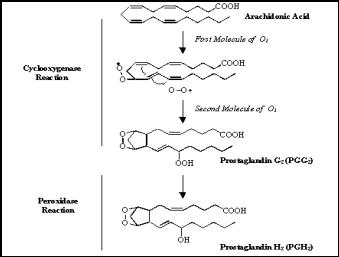

(Selective 1). COX enzymes can then

interact with the free membrane arachidonic acid and convert it to prostaglandin

form. This is accomplished by

adding O2 to the molecules in a two-step process.

These steps are outlined in Figure 2.

This unstable prostaglandin must immediately be changed into more stable

molecules (thromboxanes, stable prostaglandins, prostacyclin).

The enzyme peroxidase is conveniently coupled to cyclooxygenase in the

membrane to serve this exact purpose. When

a prostaglandin H2 is formed from the PGG2, it is free to

enter the cytoplasm, where it is permanently stabilized by another enzyme.

From there,

the

prostaglandin acts as a signaling molecule to the surrounding cells that have

prostaglandin receptors (which are G-protein-linked receptors).

When a PG interacts with a receptor, the cell is stimulated (through the

adenylyl cyclase

the

prostaglandin acts as a signaling molecule to the surrounding cells that have

prostaglandin receptors (which are G-protein-linked receptors).

When a PG interacts with a receptor, the cell is stimulated (through the

adenylyl cyclase

pathway)

to contract.

Until

quite recently, COX enzymes were inhibited by non-steroidal anti-inflammatory

drugs (or NSAIDs). These drugs,

such as ibuprofen or Tylenol, boasted pain relief to inflamed or injured areas.

However, since NSAIDs inhibited all COX enzymes without selectivity, the

COX-1 enzyme could not perform its proper function of catalyzing the synthesis

of protective PGs for the stomach and kidneys.

Thus, when taken in high doses, NSAIDs generated unwanted side effects of

GI tract infection and even stomach and intestinal ulcers.

To get enough pain relief for rheumatoid arthritis, achy joints, or

post-surgical pain, NSAIDs would have to be taken in amounts high enough to

invoke gastric ulcers. Therefore,

NSAIDs did not adequately solve the COX problem.

The

need for an effective and selective COX-2 inhibitor resulted in the research

production of two similar drugs: celecoxib

(Celebrex) and rofecoxib (Vioxx). Although pharmacies began distributing celecoxib first, with

an impressive 375-fold selectivity rate for COX-2, rofecoxib bragged a much

higher rate of selectivity (Kaplan-Malchis 27).

Yet both attempt to accomplish the same goal of inhibiting COX-2 only.

Rofecoxib

(and similar COX-2 inhibitors) is extremely selective in its enzyme inhibitions,

with an incredible selectivity ratio of COX-2 to COX-1 greater than 800:1 (27).

Since COX-2 exists in high concentrations at the site of inflammation,

the drug’s effects are detected mostly in this area.

Pro-inflammatory prostaglandins are prevented from developing,

significantly reducing swelling and acute pain at potential inflammatory sites.

Rofecoxib

is able to accomplish its task by taking advantage of a key difference in amino

acid sequences on COX-1 and COX-2. At a specific spot where COX-1 has

isoleucine, COX-2 carries a valine. The presence of the valine allows the

selective COX-2 inhibitor to bind only to that site on COX-2.

Rofecoxib searches for this valine in a COX enzyme and binds to the site

only when it is present. In this

way, the drug can selectively inhibit COX-2 from producing PGs.

Rofecoxib

is able to accomplish its task by taking advantage of a key difference in amino

acid sequences on COX-1 and COX-2. At a specific spot where COX-1 has

isoleucine, COX-2 carries a valine. The presence of the valine allows the

selective COX-2 inhibitor to bind only to that site on COX-2.

Rofecoxib searches for this valine in a COX enzyme and binds to the site

only when it is present. In this

way, the drug can selectively inhibit COX-2 from producing PGs.

Administration

of Rofecoxib

Vioxx is taken orally in doses of 12.5 mg, 25 mg, or 50 mg, with or

without food. The 50 mg tablet is seldom used, as doctors only recommend a

maximum of 25 mg per day. Since

rofecoxib interacts with certain other drugs, it should not be taken with

methotrexate, warfarin, rifampin, ACE inhibitors, or lithium (Jillard 1).

Vioxx is 93% absorbed by the body, and excreted over 99% of the time by

urine (Clinical 1). It can also be given in oral suspensions of 12.5 mg/mL or 25

mg/mL (Jillard 1).

Side

Effects

Initially, Vioxx inserts contained warnings identical to traditional

NSAIDs regarding GI tract infection and ulceration until a survey showed some

impressive results. Both U.S. and

international studies of the connection between Vioxx and endoscopic

gastroduodenal ulcers, a 25 mg dose exhibited about the same effect on stomach

lining as a placebo (sugar pill). Ibuprofen

understandably had nearly three times as many ulcer cases as the placebo.

It can be concluded, therefore, that due to the selective nature of

rofecoxib, Vioxx does not interact with COX-1 nearly as much as Ibuprofen.

Tables 2 and 3 show the results of these studies.

|

Endoscopic

Gastroduodenal Ulcers at 12 weeks

U.S. Study

|

|

Treatment

Group

|

Number

of Patients with Ulcer/

Total Number of Patients

|

Cumulative

Incidence Rate

|

Ratio

of

Rates

vs. Placebo

|

95%

Cl

on

Ratio of Rates

|

|

Placebo

|

11/158

|

9.9%

|

--

|

--

|

|

VIOXX

25 mg

|

7/186

|

4.1%

|

0.41

|

(0.16,

1.05)

|

|

VIOXX

50 mg

|

12/178

|

7.3%

|

0.74

|

(0.33,

1.64)

|

|

Ibuprofen

|

42/167

|

27.7%

|

2.79

|

(1.47,

5.30)

|

|

*by

life table analysis

|

<http://www.healthandage.com/html/res/pdr/html/52402550.htm>

|

|

Endoscopic

Gastroduodenal Ulcers at 12 weeks

Multinational Study

|

|

Treatment

Group

|

Number

of Patients with Ulcer/

Total Number of Patients

|

Cumulative

Incidence Rate

|

Ratio

of

Rates

vs. Placebo

|

95%

Cl

on

Ratio of Rates

|

|

Placebo

|

5/182

|

5.1%

|

--

|

--

|

|

VIOXX

25 mg

|

9/187

|

5.3%

|

1.04

|

(0.36,

3.01)

|

|

VIOXX

50 mg

|

15/182

|

8.8%

|

1.73

|

(0.65,

4.61)

|

|

Ibuprofen

|

49/187

|

29.2%

|

5.72

|

(2.36,

13.89)

|

|

*by life table

analysis

|

These studies show the frequency in occurrence of intestinal ulcers over

a twelve-week period for individuals who took these drugs.

For the few cases that resulted in ulcers, these side effects can be

traced back to the fact that rofecoxib is not exclusively selective of COX-2,

and in fact, some COX-1 enzymes are inhibited in the process.

This causes a rare incident of gastroduodenal ulceration.

Based on a clinical study of the negative effects of Vioxx compared with

Ibuprofen,

|

Side

Effects Occurring in ³2% of

Patients Treated with Rofecoxib

|

|

|

Placebo

|

Rofecoxib

12.5 or 25 mg

daily

|

Ibuprofen

2400 mg

daily

|

Diclofenac

150 mg

daily

|

|

|

(N

= 783)

|

(N

= 2829)

|

(N

= 847)

|

(N

= 498)

|

|

General

Abdominal Pain

Asthenia/Fatigue

Dizziness

Influenza-Like Disease

Lower Extremity Edema

Upper Respiratory Infection

|

4.1

1.0

2.2

3.1

1.1

7.8

|

3.4

2.2

3.0

2.9

3.7

8.5

|

4.6

2.0

2.7

1.5

3.8

5.8

|

5.8

2.6

3.4

3.2

3.4

8.2

|

|

Cardiovascular

System

Hypertension

|

1.3

|

3.5

|

3.0

|

1.6

|

|

Digestive

System

Diarrhea

Dyspepsia

Epigastric Discomfort

Heartburn

Nausea

|

6.8

2.7

2.8

3.6

2.9

|

6.5

3.5

3.8

4.2

5.2

|

7.1

4.7

9.2

5.2

7.1

|

10.6

4.0

5.4

4.6

7.4

|

|

EENT

Sinusitis

|

2.0

|

2.7

|

1.8

|

2.4

|

|

Musculoskeletal

System

Back Pain

|

1.9

|

2.5

|

1.4

|

2.8

|

|

Nervous

System

Headache

|

7.5

|

4.7

|

6.1

|

8.0

|

|

Respiratory

System

Bronchitis

|

0.8

|

2.0

|

1.4

|

3.2

|

|

Urogenital

System

Urinary

Tract Infection

|

2.7

|

2.8

|

2.5

|

3.6

|

Diclofenac,

and a placebo, rofecoxib was proven a relatively safe and effective drug for use

in pain management. As shown in

Table 4, Vioxx behaved more like a placebo in most cases than a drug.

About 25% of Vioxx recipients reported some type of side effect, with

only about 5% of the total patients contracting serious health problems from the

drug (Selective 1). One of the most common side effects among patients was

diarrhea (6.5%). Several isolated

cases of GI tract infection, ulceration, kidney failure, or cardiovascular

complications. All of these side

effects occur due to minute COX-1 inhibition.

Along with the severe side effects, Vioxx also causes some typical

medicinal side effects: allergic

reactions, skin reactions, liver problems (nausea, tiredness, itching,

tenderness in the right upper abdomen, and flu-like symptoms), and other minor

and rare incidents of anxiety, confusion, depression, hair loss, hallucinations,

increased levels of potassium in the blood, low blood cell counts, palpitations,

pancreatitis, tingling sensation, unusual headache with stiff neck (aseptic

meningitis), vertigo. Table 4 shows

an exhaustive list of possible side effects for rofecoxib compared with

Ibuprofen, Diclofenac, and a placebo.

Conclusion

Vioxx has a promising future as a valid treatment for arthritic symptoms,

joint pain, and post surgical recovery. Its

arrival in pharmacies is definitely a welcome relief and alternative for

traditional non-selective NSAIDs. When

taken in small enough doses, rofecoxib can effectively inhibit COX-2 enzymes,

eliminating the synthesis of adverse prostaglandins, without seriously affecting

the recipient’s health.

Works

Cited

“Adverse Reactions:

Vioxx Prescribing Information.” Merck

& Co., Inc. 26 Nov 2002. <http://www.vioxx.com/vioxx/product_info/pi/reactions.html>

Bridges, Alan J.

“COX-2 Inhibitors.” Spine-Health,

1999. 26 Nov 2002. <http://www.spine-health.com/topics/conserv/cox/cox03.html>

“Clinical Pharmacology:

Vioxx Prescribing Information.” Merck

& Co., Inc. 26 Nov 2002.

<http://www.vioxx.com/vioxx/product_info/pi/clin_pharm.html>

“Description:

Vioxx Prescribing Information.” Merck

& Co., Inc. 26 Nov 2002.

<http://www.vioxx.com/vioxx/product_info/pi/description.html>

Kaplan-Malchis, Barbara.

“A Quest for Safer NSAIDs: Focus

on the Selective COX-2 Inhibitors.” Home

Health Care Consultant. June

2000: 25-30.

26 Nov 2002. <http://www.mmhc.com/hhcc/articles/HHCC0006/kaplanmachlis.html>

Jillard, Nancy.

“Pain and Rheumatoid Arthritis: An

Update.” Drug Topics.

Medical Economics: Montvale,

2000. 26 Nov 2002. <http://www.drugtopics.com/be_core/search/show_article_search.jsp?searchurl=/be_core/content/journals/d/data/2000/0403/dce04a.html&navtype=d&heading=d&title=Pain+%26amp%3B+Rheumatoid+Arthritis%3A+An+Update>

McGriff, Nayahmka.

“Management of pain in rheumatoid arthritis.”

Drug Topics. Medical

Economics: Montvale, 2001. 26

Nov 2002. <http://www.drugtopics.com/be_core/search/show_article_search.jsp?searchurl=/be_core/content/journals/d/data/2000/0403/dce04a.html&navtype=d&heading=d&title=Pain+%26amp%3B+Rheumatoid+Arthritis%3A+An+Update>

Miceli, David.

Physician’s Desk Reference.

53rd-55th editions: 1999-2002.

26 Nov 2002. <http://www.stevensjohnsonsyndrome.com/vioxx.htm>

“Selective COX-2

Inhibitors.” The Drug Monitor.

26 Nov 2002. <http://www.home.eznet.net/~webtent/coxi.html>

The two

COX enzymes exist in different concentrations throughout an organism. At inflammation sites, COX-2 is much more abundant.

Since COX-1 helps produce prostaglandins that protect the stomach lining,

it is present in larger quantities in the GI tract.

Because typical NSAIDs are not selective when targeting enzymes, they end

up shutting down prostaglandin synthesis everywhere in the body.

This results in a greater risk of GI tract infection and ulceration,

inciting research to develop a drug that inhibits only COX-2, the more

pro-inflammatory of the two enzymes.

The two

COX enzymes exist in different concentrations throughout an organism. At inflammation sites, COX-2 is much more abundant.

Since COX-1 helps produce prostaglandins that protect the stomach lining,

it is present in larger quantities in the GI tract.

Because typical NSAIDs are not selective when targeting enzymes, they end

up shutting down prostaglandin synthesis everywhere in the body.

This results in a greater risk of GI tract infection and ulceration,

inciting research to develop a drug that inhibits only COX-2, the more

pro-inflammatory of the two enzymes.

the

prostaglandin acts as a signaling molecule to the surrounding cells that have

prostaglandin receptors (which are G-protein-linked receptors).

the

prostaglandin acts as a signaling molecule to the surrounding cells that have

prostaglandin receptors (which are G-protein-linked receptors). Rofecoxib

is able to accomplish its task by taking advantage of a key difference in amino

acid sequences on COX-1 and COX-2. At a specific spot where COX-1 has

isoleucine, COX-2 carries a valine. The presence of the valine allows the

selective COX-2 inhibitor to bind only to that site on COX-2.

Rofecoxib

is able to accomplish its task by taking advantage of a key difference in amino

acid sequences on COX-1 and COX-2. At a specific spot where COX-1 has

isoleucine, COX-2 carries a valine. The presence of the valine allows the

selective COX-2 inhibitor to bind only to that site on COX-2.