Table of Contents

2. Comparison between American and Japanese Medical Education-2000

4. My personal thoughts about Japanese medical education and health care-1997

5. Physical examination (PE) skills of first year residents

6. Ideal skills for junior residents(JR)

7. Creative Thinking-Clinical Problem Solving Resident Physician Training program Kameda Medical Center-1995

8. Clinical Rounds.: Website URL:-1996-1999

1. Stein G.H., Improvements of Japanese Surgical Training for the 21st Century: Problems and Suggestions Based on my 7 Years Teaching Basic Bedside Skills in Japan. Journal of Japanese College of Surgeons 2001. 26:14-19

ABSTRACT

The application of the methods of problem-oriented system and

problem-based learning are essential tools for teaching surgically

oriented Japanese physicians-in-training the clinical skills to

understand and manage their patients' problems independently.

Much time is needed during the first post graduate year in order

for these young physicians to become proficient in patient analysis.

The use of pre-printed worksheets and detailed repetitive medical

chart review with immediate corrective feedback, coupled with

bedside practical examinations and discussions, facilitate acquisition

of needed clinical skills. Surgical trainees need these basic

cognitive skills if they are to develop the proper skills for

understanding pre- and post- procedural invasive interventions.

Additionally surgical training should include the use of medical

literature for evidence based decision making as well as communicative

skills for talking with patients and families. These patient oriented

discussions should be in conformity with international ethical

standards. Future computerized patient interactions will require

surgeons to accept new models of clinical involvement. Life-long

continuous medical education will be essential as these new

technologies

are introduced. Young surgeons will lead the changes; old surgeons

will have to adopt the new methods or retire.

Key words: Japanese medical education, surgical

residency,

clinical skills, problem oriented system POS

Getting Started in Japan

After practicing and teaching clinical medicine for 22 years in the Department of Medicine, College of Medicine, University of Florida, Gainesville Florida, USA, I embarked on a teaching career in Japan, initially at the invitation of Dr. Tadashi Matsumura, Maizuru Municipal Hospital. While short-term teaching in Maizuru City, I received a invitation for a permanent position at Kameda General Hospital in Chiba Ken and remained there for 7 years as director of medical education and professor-in-residence. While at Kameda General Hospital I regularly consulted with many other medical facilities, such as Shonan Kamakura Hospital, Okinawa Chubu Hospital, St. Luke's International Hospital, Chiba University Hospital (2nd Department of Medicine), and US Naval Hospitals in Okinawa and Yokosuka. Varied bedside teaching experiences in these hospitals enabled me to develop a method of teaching young Japanese physicians basic clinical skills, based on the Problem Oriented System, used thought out US Medical schools for the past 30 years, which I modified for the Japanese medical educational system.

It is important for all graduating medical students and clinical residents to have these basic clinical skills for their further development as independently thinking and competent clinicians, regardless of their intended field of specialization.[1]

Problem Oriented System(POS) and Problem Based Learning(PBL)

POS refers to physicians' systematic method of organizing clinical data in order to understand patients' medical illnesses from each patient's medical history, physical examination, and laboratory data, permitting the physician to construct an individualized assessment and plan.[2] PBL is a similar systematic learning method based on the POS, used by medical students in tutorial group discussions, in which students discuss clinical cases from notes prepared by the tutor, who is characteristically a senior physician.

With either method, the student or resident organizes the clinical data, identifies the problems by creating a problem list from the history, physical examination, and laboratory data. The problems are grouped to form assessments which include likely diagnoses and differential diagnoses. The plan of studies and treatment must show that the student is following medical logic by supporting the plan from the assessment which in turn is supported by the history, physical examination, and laboratory data.[3] Learning involves using the students' accumulated fund of medical knowledge and finding published information to fully support their assessments. Self study from handbook and textbook assist the students in building their own database of medical facts to apply to the clinical problems.

Identifying Residents' Clinical Skills

As my teaching experiences expanded, I sensed the the need to evaluate residents' basic clinical skills in a systematic fashion. However, because of my rudimentary Japanese language skills, I was unable to assess residents' history taking from their patients[4]. Hence I focused on residents' physical examination skills, which I could readily observe.

In that context, I set up a observational study at Kameda General Hospital, which was approved by their postgraduate medical educational committee. Each first-year resident was invited, then instructed to perform a complete physical examination on a patient within a 30 minute time limit. I observed their skills by marking each of 45 physical examination items on a standardized conventional check -list, as the resident performed the task, without regard to quality of the performance.[5] The first phase of the study, called the pre-test, was done during the first week of the 6 month internal medicine rotation. Corrective feedback for improving their skills as well as a copy of their check-list was given each resident. The post-test was a physical examination repeated on a different patient with the same time limit and check-list during the last week of the 6 month internal medicine rotation.

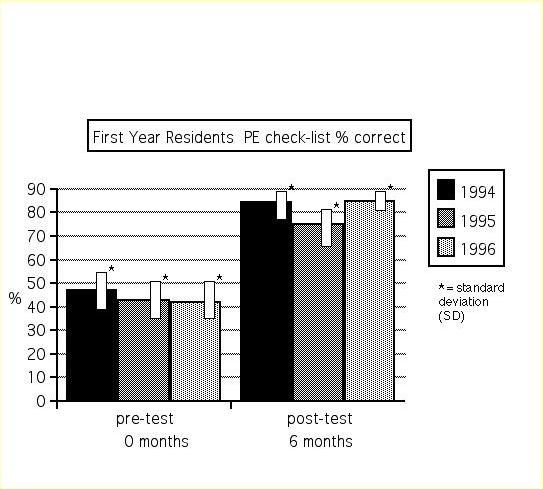

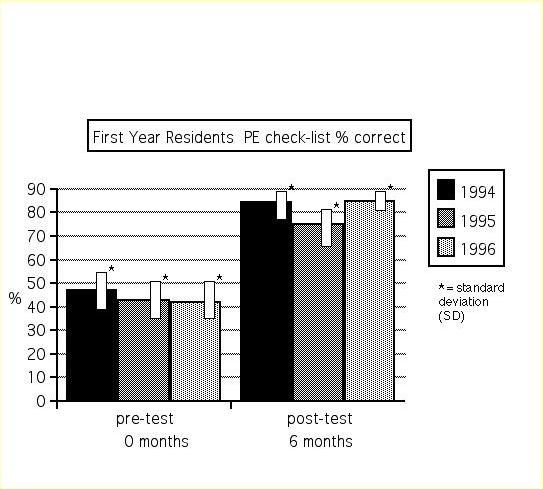

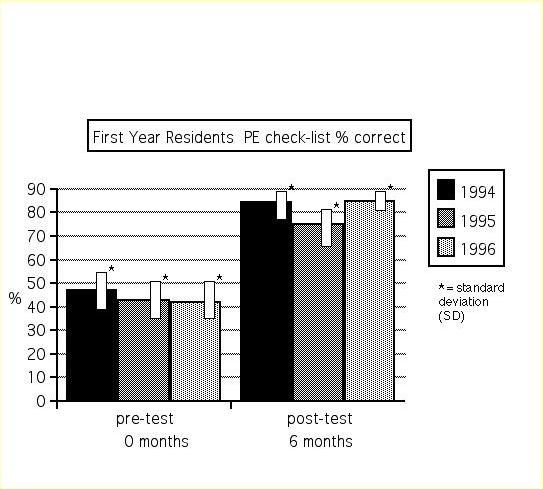

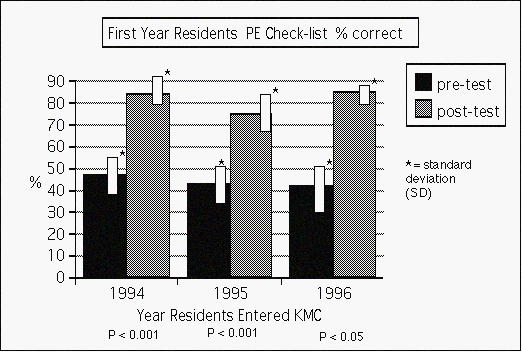

The results are shown in the Figure. Ten residents were observed for each of 3 years (10 residents multiplied by 3 years, or 30 residents in total). The pre-test results showed that the recently graduated medical students, now residents, performed about 45% of the items considered to be part of a usual physical examination. The post-test results showed that after 6 months of the internal medicine rotation, their performance rose to 80% of the items on the same check-list.

My conclusions of this quantity-identifying study (no attempt was made to asses the quality of the skill) was: 1) Entering 1st year residents have rudimentary physical examination skills; 2) Their skills improved by 100 % showing their ability to learn; 3) In comparison, US medical students are required to have a score of 90 % to pass a similarly observed physical examination check-list at the conclusion of the class[6].

On a daily basis I observed that their initial skills to use the POS for patient understanding was similarly poorly developed. Again I was unable to quantify these observations. I subsequently evolved a method of teaching the POS in spite of my poor Japanese language skills

Teaching POS: Setting

Instruction was held in a small conference room twice daily, each session lasting 1 1/2 hours 5 days each week for 2 months while the residents were on the general internal medicine rotation. Two to four junior residents discussed their cases with me as best they could using the POS method; each resident had about 2 new inpatients each week and managed 5-7 inpatients under my and the chief of service's supervision. Following the daily afternoon conference, bedside rounds were conducted for about 1 hour. Residents communicated in English, which in all cases improved during the 2 month interval. Their written case reports were usually in English since their English reading and writing skills were somewhat better than their conversational skills.

Teaching POS: New Inpatient Presentations

The residents were required to use pre-printed work sheets. The work sheets were developed from the standard University of Florida School of Medicine physical diagnosis class handbook by Akira Naito, MD, my former 2nd year Kameda General Hospital resident, under my supervision. Work sheets guided their data collection, showing them the needed data and providing a structure to formulate their problem list, assessment, and plan. The residents presented their cases the morning after the day of admission from the worksheets. This seemingly strict requirement enabled the staff to advance the work-up and management of the patient in a more orderly and expeditious fashion. In addition, residents were guided through their own interpretations of their patients' ECG's and imaging studies. During their case presentations I encouraged residents to support their assessments and plans from handbooks, textbooks, and at less frequent times, MEDLINE literature searches as a gentle introduction to evidence-based medicine. I lead the discussions with corrective feedback of information, praise and encouragement, requiring much patience on my part.

Teaching POS: Current Inpatient Presentations

The residents orally presented their current patients' progress from the patients' medical chart, using the exact S.O.A.P.[Subjective-history; Objective- focused physical examination and laboratory data; Assessment; and Plan] format. In addition the residents presented their assessment and plan at the bedside of each of their patients daily. This provided the opportunity for me to clarify the history and physical examination, thus providing direct corrective feedback to improve their bedside skills.

Teaching POS: Lectures

Lectures were limited in frequency to emphasize the importance for residents to focus on their own patients' problems, to perhaps 2-3 short lectures each week during the twice daily rounds. Journal articles were selected for practical common disease management, each resident being given a photocopy. Use of these articles served to emphasize the importance of using evidence-based medicine to make practical bedside decisions. Internet MEDLINE articles were similarly presented and discussed. Ethical issues were introduced as the patients' situations arose, including "informed consent" and "do not resuscitate" (DNR). Cultural issues, such as understanding differences of opinion between physicians, explaining other physicians' failure to use evidence-based medical literature for their decisions, and our own and other physicians' errors, were openly discussed.

Teaching POS: Personal Observations

I observed that, in general, entering first year residents, immediately after graduating from medical school, have inadequate basic clinical skills, lack confidence, or are overconfident, and are deficient in analytical problem solving ability. However, their skills dramatically improved during an intense 2 month training, surpassing the skills of senior residents who have not received interactive POS training. The use of worksheets permitted the residents to know the expected and needed data to compile a problem list, assessment, and plan. Corrective feedback of information and praise encouraged residents to ask questions and seek their own answers, a process of interactive learning. Patience was essential; each resident learned at a different rate, some quickly, others slowly. I felt it was necessary for residents to hear that I, as surely is the case with all senior physicians, have incomplete medical knowledge, uncertainties, and insecurities with some of my medical decisions. Residents observed me seeking firmer basis to finalize decisions from consultants and literature searches when uncertainties occurred.

Teaching POS: Conclusions

Concerning the POS, this method, when properly implemented with 2 months of intensive study, dramatically improved the inadequate clinical skills on first year residents. Daily recitations and bedside presentations by residents of each patients' problems enhanced acquisition of basic clinical skills. Corrective informational feedback and personal encouragement developed correct levels of confidence and independent problem solving skills. A successful clinical instructor needs to interactively focus on teaching clinical skills and be very patient as the resident slowly matures into a trained physician. I also suggest instructors reveal their uncertainties and insecurities. When these occur, they might increase their use of consultants and literature searches.

Teaching POS: Application to Surgical training

Surgical residents need problem-solving skills just as all clinicians need these skills, without exception. Examples abound in every aspect of surgical care performed by surgical residents. I mention some of them here. A patient enters a local emergency room with abdominal pain. The surgical resident must think about the clinical findings via history and physical examination, make a problem list, then construct an assessment with differential diagnosis leading to the logical plan of studies and the plan of treatment. If surgery is considered, the indications for the operation must be specified, including the application of current clinical guidelines and/or critical pathways of patient management. Meticulous preoperative care is another learned application of POS, including fluid, blood pressure, fever, and prior medication management. When the resident's mind is fertile for creative thinking, interpretive solutions to unique situations during the surgery will lead to better surgical outcomes rather than rote techniques. Post-operative management is yet another application of POS, for residents to learn fluid balance, wound care, fever, etc. Surgical out-patient care when focused on problems, assessment and plan provides a logical framework for residents' education. Lastly, ethical considerations, such as informed consent for surgery and DNR for terminal cancer patients, need to be learned at every phase of patient management.

Surgical case illustrating POS

Perhaps a description of an actual surgical case might highlight the importance of the application of POS to surgical patient care. The plastic surgical patient case was kindly provided by surgeons Kenishi Arashiro, MD and Kunihiro Ishida, MD. Their patient was a middle aged man who was brought to the Okinawa Chubu Hospital emergency room with a large rail impaled through his face. The rarity of this injury necessitated that basic surgical principles be applied. These included stabilization of the patient by assessing the "ABC's" of airway, breathing and circulation. Trauma management is best performed by using the standardized algorithms for advanced traumatic life support(ATLS). These procedures are best learned in the POS format with simulated practice to affect the resuscitation smoothly. Creative thinking is necessary to conceptualize the detailed anatomy of the damaged structures. Thinking that the impalement might have impinged or perforated the carotid artery, the surgeons elected to leave the rail in place prior to its surgical removal. Also time for removal was perceived to be of essence which meant preoperative studies had to be minimal. A surgical resident might have done an Internet MEDLINE search on impalement injuries for guidance. Once the surgical removal had started, creative thinking was again necessary to preserve the damaged organs, blood vessels and nerves. Of course, dexterity skills were necessary for the successful outcome.

During the operative repairs, there is frequently time to instruct the resident in surgical principles involved in this case using the POS. The post-operative problems of fluid balance, electrolytes and fever are best learned by the POS. Lastly the ethical considerations of informed consent with the patient's family might have included the high risk of death and other complications from the removal of the rail. It is a credit to these skillful surgeons that their patient had a successful outcome, which they felt was mostly due to their strict adherence to basic surgical principles, again learned through POS.

Futuristic surgery

Change is occurring in every field of medicine, no less so in surgery. Building on the present, I predict the following changes will happen in the surgical field. Computer applications for the collection of patient data including history and laboratory results, with the generation of problem list, assessment and plan, will become commonplace, Computer simulated learning of surgical procedures will require residents to be facile with computer use. An increasing development of robotic surgery, guided by surgeons, will occur. Organ and stem-cell transplantation will have many more uses. Applications from the human genome project will change the nature and course of many common diseases, perhaps reducing the need for certain surgeries. Nanotechnologies will become useful surgical tools. An example of these microscopic devices might be a tiny item which removes atherosclerotic plaque from vessel walls. Another prediction is that patients will use computers to assist with the management of their chronic diseases, reducing their dependence on physicians. This trend is developing in many Western countries. I leave it to the readers' and science fiction writers to dream of further possibilities, some of which will undoubtedly come true.

Futuristic Surgical Training

The impact of these and other difficult-to-predict changes on surgical training might be the following: Basic clinical skills may be de-emphasized. However, clinical reasoning skills will retain their prime importance[7]. Computer skills and its applications will become an important component of training. Life-long continuous surgical education will be essential as these developing technologies are introduced into community surgical practice. Young surgeons will lead the changes; old surgeons will have to adopt the new methods or retire.

References

1. Kassirer, JP. Teaching problem-solving - how are we doing.

N Engl J Med 1995;332:1507-1508.

2. Weed LL. Medical records that guide and teach. N Engl J Med

1968;278:593-600 and 652-657.

3. Weed LL. The problem oriented record as a basic tool in medical

education, patient care and clinical research. Ann Clin

Res.1971;3:131-134.

4. Voytovich AE, Rippey RM. Knowledge, realism, and diagnostic

reasoning in a physical diagnosis course. J Med Edu 1982;57:461-467.

5. Bates B, Hoekelman RA. A Guide to Physical Examination. 6th

ed. Philadelphia: J.B.Lippincott, 1995.

6. Stein GH. Comparison between American and Japanese medical

education. Journal of Okinawa Chubu Hospital. 2000;26: 45-51.

7. Weed LL. Sounding Boards. Physicians of the future. N Engl

J Med 1981;304:903-907.

Figure Entering first year residents quantitative per cent correct physical examination items at the start (pre-test) and 6 months at the end (post-test) of the internal medicine rotation, performed over 3 years with 10 residents each year

2. Stein

G,H., Comparison between American and

Japanese Medical Education. Journal

of Okinawa Chubu Hospital 2000.269(1):45-51.

American Medical Education

Goals of American Medical Education: an improved method of clinical skill training

Outline

1. Development of basic clinical skills for logical thinking and

solving clinical problems

2. Integration of the basic sciences of human disease with clinical

medicine.

3. Interactions with junior and senior physicians and consultants.

4. Learning to use medical literature searches for clinical decisions

based on evidence.

5. Development of life-long learning patterns.

6. Participation in peer review and quality assurance.

7. Discussions of community ethical issues.

Details of logical problem solving: The first goal

The main goal of North American clinical training is the development of the basic clinical skills for medical student and residents to manage their sick patients independently. These basic clinical skills which are taught to each medical student include eliciting a useful focused complete medical history, performing a thorough physical examination and selecting the essential laboratory tests. Further the integration of this information, obtained from the patient and clinical laboratory, enables the medical student to formulate a problem list from which diagnosis emerge. This method may be called S.O.A.P. [Subjective (medical history), Objective (physical examination and laboratory data), Assessment (diagnosis) and Plan(further studies and treatment)] or P.O.S. (Problem Oriented System).

As the patient's clinical course progresses, the medical student becomes skillful in altering the problem list with changing assessments and clinical plans to improve the patient's management and outcome. I may use the terms medical student and resident interchangeably. since there is overlap of these positions in Japan. Hence these creative problem solving skills are taught each medical student/resident with one patient at a time. These abilities are necessary because each patient is unique. This uniqueness and variability between patients with the same disease must be fully understood if the medical student/resident is to successfully grasp and manage the clinical problems of his patient. Independent thinking can be learned by each medical student/resident. Dependence on senior physicians for answers to clinical problems will inhibit their development. Each trainee must learn to think for himself and to find the answers himself.

Perhaps selected details of these skills might be helpful. Firstly regarding history taking, the incorporation of the review of systems(ROS) specific for each problem of the present illness permits the resident to literally learn about the disease from the patient. In some cases this might mean that the medical student/resident must read about the probable diagnosis in a standard textbook of medicine to learn the important questions to ask the patient, then return to the patient's bedside for further history taking. Also medical students/residents are required to ask most of the questions from a standard ROS listings. Secondary patient problems are uncovered frequently by this method. Further, residents are shown how to review hospital charts of prior admissions for complete data retrieval. They are instructed in techniques for telephoning community physicians for greater data input. These refinements enable the medical student/resident to have complete subjective data about his patients.

Regarding the so called objective component of clinical skills, namely the physical examination, there is a special emphasis: the psychophysical skills of finger and ear training, that is, palpation, percussion, and auscultation. Frequent bedside demonstrations of patients with cardiac murmurs, organomegaly, neurologic signs, arthritic joint limitation, etc., enable the medical student/resident to acquire these important skills. Routine laboratory data are analyzed for significance of both normal and abnormal results. The medical student/ resident then formulates a problem list, writing down every important item from the subjective and objective data base. Related problems are grouped together. From the reorganized problem list the assessment list is developed, fully integrating the clinical data into a useful and prioritized understanding of the actual clinical situations. The plan of needed studies to support the evident as well as the differential diagnosis is then developed. Readings in medical textbooks and consultations with specialists are encouraged. Lastly the plan of treatment, with drugs or surgical intervention, is discussed.

Hence the tool needed to understand the initial evaluation of the patient, namely the S.O.A.P. method, is slowly taught each medical student/resident, one at a time, over a 2~4 year period. The instruction takes place on a small conference room and at the bedside of the patient. As the resident presents his/her patient, he/she is guided supportingly through the S.O.A.P. steps. The resident is assisted with further history questioning of the patient for clarification of the illness and understanding the impact on the patient. At the bedside these further questions are asked and analyzed; the resident's hands on the patient are trained to feel correctly; ears on the stethoscope are tuned to hear gallop rhythms and murmurs. The patient's clinical course is followed closely. Each problem or assessment is understood within the S.O.A.P. format on a daily basis. This requires the resident to examine the patient and review the medical chart daily; progress notes using the S.O.A.P. system are encouraged. Immediate feedback of successful actions of the resident cultivate confidence in the newly acquired clinical skills. Other training methods include daily conferences and monthly morbidity and mortality conferences. Clinical procedures, from simple bedside ones to complex ones using the latest technologies and equipment are taught by competent staff. Residents receive frequent evaluations of their development and clinical skills to assist with their improvement and career choices.

Integration of the basic sciences of human disease with clinical medicine

Another goal of the training program is the integration of the basic sciences into clinical practice. The resident is continuously encouraged to keep asking why the particular clinical course developed. The usual medical model of antecedents, that is, what came before each event, and before that event, etc. is explained in pathophysiologic terms. By this method, there is a stimulation of medical curiosity to review applied aspects of anatomy, physiology, biochemistry, pathology, microbiology and pharmacology for each of the resident's patients.

Interactions with junior and senior physicians and consultants

Successful interactions between junior and senior physicians teaches mutual respect and helpful interdependency. It is a kind of team concept with each level of physicians teaching those lower in years of study. Those with longer years of experience, however, must keep an open mind to learn from their juniors, who may have newer information to contribute.

Learning to use medical literature for clinical decisions based on evidence

A recently developed technique for improved patient care is evidence based clinical practice. The basic concept is that physicians are trained to use the medical literature to support their decisions. Use of textbooks and computerized literature searches must be freely available to residents. Toward that goal residents at American teaching hospitals are learning how to use the library's data base via computer and textbook to support their clinical choices.

Development of life-long learning patterns

Such literature searches underscore the reality of continuously changing medical information. This should result in the resident's understanding that to practice contemporary medicine requires continuous life long devotion to reading the medical literature. An additional aspect of using these modern tools of contemporary medicine is the gentle challenge by residents to senior physicians who might have reached faulty conclusions based on outdated data.

Participation in peer review and quality assurance

Another topic is resident participation in peer review and quality assurance. These physician directed programs aim to improve patient care by analyzing physician management of selected problems. A possible example to illustrate peer review might be that physicians analyze medical charts of all patients dying from causes such as acute myocardial infarction or even unknown causes. If the causes of the death are not well evaluated or errors occurred in patient management, then the treating physician is required to explain his treatment plan. If his explanations are not satisfactory to his peer physicians, they may require him to take postgraduate medical education courses to improve his skills, or monitor his care of patients. Peers might even restrict his practice in extreme situations. Although this example is a hypothetical situation, it is similar to current medical practice in North America and parts of Western Europe.

Quality assurance(QA) is slightly different from peer review: more hospital wide indicators of quality of care are selected and analyzed. At American hospitals, QA programs are fully developed. For example surgeons are collecting data on their patients' return to the operating room for corrective surgery after the initial surgery. Another example is internists are collecting data on return of their patients to the intensive care unit following recent discharge from the I.C.U. Such data analysis should show physicians as well as nurses and administrators better ways of patient management.

Discussions of community ethical issue

A final topic that is the ethical understanding of patient care. Some of the areas of interest concern informed consent, that is, telling the patient what to expect from medications and procedures, both benefits and possible harm with poor outcomes. Further, residents are actively assisted with managing the patient and his/her family when death is approaching. Do not resuscitate(DNR) orders are fully explained to residents, nurses, and the patient's family.

Features of the American medical educational system

The reasons for ranking American medical educational system as one of the best in the world are as follows: Logical thinking method is the best way to understand comprehensively patient problems. Personal opinion and learning by watching and observation, the traditional methods of acquiring new skills, are less important in the American system. There residents and medical students are actively taught and closely supervised much greater than in many other developed countries. Teaching physicians enjoy discussions with residents about their patients; they bring current articles from the medical literature into the daily rounds. This 'evidence based' clinical medicine method insures that current information is applied to the patient's problems, that personal opinion is less important than published data, that senior physicians learn from junior physicians when such younger physicians have better information. Young physicians are urged to use and follow national consensus clinical guideline for patient diagnosis and management. Such use builds confidence among physicians. Physician arrogance mostly evolves from physician insecurities. The American teaching team aims to reduce both residents' arrogance and insecurities.

The group feelings are very different from those in Japan. In America all senior residents supervise junior residents. They do not have their 'own' patients as in Japan. Medical students (equivalent to first and second year residents in Japan) are supervised by their senior and junior residents. Senior physicians supervise all members of the team. Note however, independent logical problem solving is encouraged at every level. None may advance to the next year's higher level without proof of satisfactory performance. There is no automatic promotion. Those medical students and residents deficient in clinical skills are required to repeat the year and may be removed from the program. Hence as residents advance to the next higher level, they develops confidence in their clinical skills; they have passed practical tests; they have less insecurities and less need for arrogance. Also the practical aspect that senior physicians are regularly learning from junior physicians keeps the senior physicians from becoming arrogant while boosting the confidence that the junior physicians have meaningful contributions to make.

Differences between American and Japanese training

Another major difference between American and Japanese training programs is the pace of the workload. In America junior residents admit about 4 patient each day; the senior resident who is supervising 2-3 junior resident is responsible for 8-12 daily admissions. The work place has a rapid pace of evaluation and treatment of inpatients; the average length of stay is about 6 days. Residents are on call for emergency admissions every 4 th evening, night and weekend; they spend the entire night in the hospital, at times without sleep. For the 3 other evenings and weekends, they may 'sign out' to the on call team, leaving the hospital in the early evening. At many Japanese teaching hospitals, junior residents admit about 2 patient a week; senior residents about 4 patients a week. The length of stay is about 16 days. Senior residents may not supervise junior residents. There is no standard admission day; all days are admission days. There is no formal 'sign out' system; residents informally make their own arrangements. Residents have not been required to be in the hospital during the night. Most residents remain in the hospital until the late evening; even when they have no patient work they stay late to talk to other physicians and nurses to convey the group's sense of togetherness.

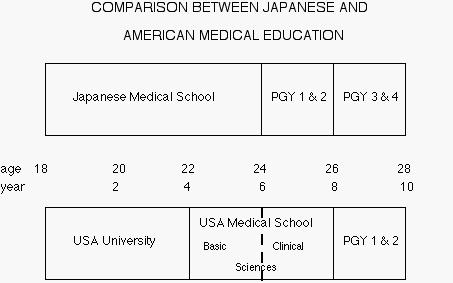

The implications of these differences may not be apparent. In the American system the residents have many patients in a short period of time. Clinical skills are learned rapidly, generally by 2 years in non-procedural programs. There is lots of stress for residents working in teaching hospitals. In Japanese teaching hospitals, the pace is more relaxed; there is much less stress for residents. However it takes a longer time to adequately develop clinical skills; it may take 2~3 extra years of post graduate training to equal the 2 years of American residency. Note that medical education in America requires 8 years of study for the M.D. degree, then 2-4 or more years of residency. In Japan medical students study for 6 years at the university, are awarded a MB (Bachelor of Medicine) degree; then they continue their residency training for minimum of 2 years, Some continue training for an unspecified duration, perhaps from 1 to 8 years additionally. An advanced medical science degree may be awarded during this interval for those enrolled in a university program. Hence the first two years of Japanese postgraduate medical education, that is, residency, should be considered equivalent to the last two years of American medical school.

Medical student differences

On a related topic American medical students attend all their classes. The lectures and related laboratories are very practically oriented. No one sleeps during lectures. Weekday evenings are spent studying. Weekend parties are small with modest amounts of alcohol consumption. Japanese medical students frequently do not attend lectures which are predominately related to the professor's research. The lectures are considered boring; many sleep during these times. There are frequent parties with much alcohol consumption. Of course there are exceptionally different students on both sides of the Pacific.

Medical chart differences

The patients' medical chart also reflect differences. All American physicians are required to have precise collection of patient data; detailed admission histories and physical examination, logical assessments and plans with at least daily complete logical progress notes. All medical charts are reviewed. Failure to comply results in penalties against the physician. Chart work is extremely important because it documents the physicians thinking processes and the exact patient course. In most Japanese hospitals, chart work may be required; it is rarely reviewed except for billing purposes. I know of no penalties for incomplete chart work , except, again, for billing purposes. A greater proportion of American hospitals use the computerized medical chart for history and physical examination recording as well as for progress notes

Advantages and disadvantages of the American and Japanese systems

On a related topic, I am frequently asked by medical students and residents to explain the differences and advantages of the American system of medical education., in two minutes or less. One the one hand, I tell them there is no advantage for them to aspire American residency training. This is because the Japanese medical education is a complete system, with training and life-long career practice relatively comfortable for the Japanese practioner. The Japanese health care system is focused on the physician in a paternalistic manner. Conformity to the group norms makes for a comfortable, stable practice environment, without threat of malpractice from irate patients. The Japanese educational framework from primary school through graduate education fosters discipline and obedience to authority; individuality and creative thinking are either discouraged or not overtly encouraged. On the other hand, the rigors of precise clinical problem solving skills are sub-optimal, errors in patient management are relatively frequent, harm to patients is overlooked without criticism or feedback to the practioner, medical chart work poorly documented, all resulting in many instances of both over and under treatment. Some exceptional Japanese teaching hospitals, such as Oaken Chub Hospital, as well as medical students and residents intrinsically recognize this dilemma and desire change and improvements.

The American system of medical education has been know for its openness to group discussions, sharing of ideas regardless of position or status and dedicated focus on the patient. Evidenced-based clinical decisions have power over personal opinions, even those of the professor. Accountability and a vigorous system of checks and balances enforces the patient- centered practice milieu. Problem solving skills and creative thinking are introduced in primary schools and enhanced throughout the maturation of the competent clinician. American medical practice requires a balance between the science of medicine(evidence-based data) and the art of medicine(caring and biomedical ethics). These listed advantages of the American system must be understood in the context of disadvantages. For example any physician may make a mistake. However, such errors in clinical judgment may bring stiff penalties in my country. The freedoms of independence and clinical practice are being limited these days by the necessities of curtailing the enormous national health care expenditure, currently 14-15% of gross domestic product (compared to about 7% in Japan). These financial limits are already impacting on postgraduate medical education in ways that are partially detrimental to residency training. Decreased length of hospital stay for in-patient care decreases total costs at the expense of decreasing the educational training benefits to residents. Residents are becoming mere overworked data managers with little time to think about and discuss their patients' problems. Managed care forces residents to attend to greater number of patients each day and week without comprehensive care for their needs. The prior years training balance between education and labor is shifting toward decreasing educational efforts and increasing toil. To add further difficulties to the burdensome resident's life, training programs are reducing the number of available residency positions while increasing the patient load. These reductions are occurring because of an over-supply of physicians. The brunt of these reductions will occur with international medical graduates(IMP) seeking training in America. Hence the opportunities for IMP to obtain American residencies are being restricted currently with greater limits planned for the future.

International medical graduate training in America

Because of the perceived successful Japanese

medical educational system by Japanese, and because of the generally

low level of English language speaking

skills, they have made up a very small percent of IMP in America.

The largest numbers of IMP are from India(20%), Pakistan(12%)

and the Philippines(9%). Japan is not among the top 10 countries

having participants in American postgraduate clinical training

programs.

In considering these advantages and disadvantages in the American system, Japanese young physicians should understand that no system is perfect, each has benefits and detriments. Yes, I clearly find many advantages to the Japanese system, as for example, its gentleness to colleagues, its forgiveness for physician errors and the security of its ikyoku system. But overall, there is no doubt in my mind of the superiority of the American medical educational system.

Advantages to remain in Japan for clinical training

Fortunately there exists a small but highly dedicated group of serious minded bright Japanese medical students, residents and senior physicians wanting to improve this deficient state of medical training and practice in Japan. It is to this small determined group that I devote my energies to support and encourage their struggles to understand analytic problem solving skills, the foundation of Western medical practice. For the average residents I have helped train at many Japanese teaching hospitals, I do not encourage them to study in American., for the reasons stated above. Rather it is my hope that through exposure to the American system as exemplified by Oaken Chub Hospital's successful medical educational programs, exposure to select Japanese national medical educational leaders, contact with Western trained medical educators, a growing number of Japanese physicians will have increasing influence to modify the tradition - bound restrictions inhibiting the proper development of clinical training and practice in Japan. These necessary modernization modifications include the field of biomedical ethics as well. The international medical communities have agreed that informed consent requires the end of the paternalistic physician role, supplanted by the decision control vested in the patient's (or his/her surrogate ) informed consent to all management and treatment issues.

Conclusion: Japan must improve clinical training

For a financially rich and developed county as Japan clearly is, with its internationally acclaimed automotive and electronics industries, its medical education and heath care practices are well below Western standards. I predict the aging of the population will force changes which I can only hope will improve clinical practice. The Japanese people deserve better care than is currently available. Okinawa Chubu Hospital is one of the facilities with a national reputation to lead improvements in Japanese health care into the 21 st century.

Biography of Gerald H. Stein, MD, FACP[in Japanese]

Dr. Stein, a native of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA, graduated

from the University of Pennsylvania ,School of Medicine. After

two years of residency at the Boston City Hospital, Harvard Seervice,

he completed his clinical training for 3 additional years at the

University of Florida Teaching Hospital, Gainesville, Florida.

For the next 20 years he held several positions at that College

of Medicine. Tadashi Matsumura, MD, invited Dr. Stein to be visiting

professor at Maizuru Municipal Hospital in Kyoto ken. Shortly

thereafter the Kameda brothers invited Dr. Stein to teaching at

Kameda General Hospital. He acceepted the position as director

of medical education and professor-in-residency, which he held

for 7 years. During those years he was teaching consultant at

many Japanese hospitals including Chiba University Hospital, St.

Luke's Hospital, Shonan Kamakura Hospital, the American Naval

Hospital, Yokosuka, and Okinawa Chubu Hospital. He has lectured

at several Japanese teaching hospitals as well. Currently he is

visiting professor of general internal medicine, Okinawa Chubu

Hospital, and consultant Okinawa American Naval Hospital. His

faculty appointments are Associate Clinical Professor, University

of Hawaii and Courtesy Assistant Professor, University of Florida.

3. Stein, G.H., A Realistic Assessment about American Residency Training for Japanese Medical Students and Residents: My Four Years Teaching in a Japanese Hospital. In: Teruya, J., ed., A Guide to American Clinical Training: Practical Advice and Personal Experiences. Medical Sciences International, LTD. Tokyo 1997. p. 337-351

4. My personal thoughts about Japanese medical education

and health care

Noguchi Medical Research Institute

Annual Fellow Report, 12/97

Congratulations to Noguchi Medical Research Institute(NMRI) on

the conclusion of a most successful year. While I do not have

exact data of numbers of candidates participating in the various

programs, I have the feeling that the quantity and quality of

its new members have significantly increased. Further increases

are anticipated as the news about the exciting clinical training

opportunities are disseminated to Japanese medical schools and

teaching hospitals.

The recent availability of the facilities of the University of

Hawaii(UH) in Honolulu presents unique opportunities for Japanese

medical students and young physicians. The program launched this

fall, 1997, provides a complete American clinical experience under

the capable direction of Edward Morgan, MD, Associate Professor

and Director, Division of International, Department of Medicine,

University of Hawaii. NMRI's successful candidates have started

the month-long subinternship at Kuakini Medical Center. When the

candidate has adequate English language communication skills,

he/she is assigned patients for direct management under the supervision

of the medical staff. This means the participant writes orders

and plans the studies and treatments of the patient. In other

words, the subintern is not an observer but an active member of

the in-patient management team. Hence increased benefits of learning

clinical skills by 'hands-on' experiences enhances the value of

this training. In addition each subintern examines a patient under

direct observation of the ward team member both at entry into

the program and at its conclusion one month later. This 'clinical

skills examination' (CSE) includes an oral and written case

presentation

to the staff observer. The observer then makes a written critique

of the strengths and weaknesses for the subintern to see the

improvements

over the month and the areas needing further development.

I anticipate there will be helpful additions to the UH program

in the near future. Planned for implementation are drills for

brief clinical evaluations of simulated patients. These drills

should better prepare NMRI members for the soon to be required

clinical skills assessment for the ECFMG certificate, starting

7/98. Under preliminary discussion is the expansion of fields

of clinical study to include general surgery as the first offering

beyond general internal medicine. I hope other areas of clinical

medicine will be added thereafter to include pediatrics, OB/GYN,

and ER medicine.

Another aspiration I have for the future is for NMRI to increase

the number and scope of its goals for applicants. By this I mean

the greater number of participants in the UH program, the greater

the impact will be on Japanese medical education. The goal issue

is similarly important. Currently all successful NMRI candidates

must have a strong desire to try to enter American residency training.

That is a fine goal which I fully support. However, I am convinced

that a lesser goal should be considered, namely, to accept suitable

candidates whose goal is to experience the American health care

system as clinical clerks rather then as subinterns and not have

the immediate desire for American residency nor have taken or

plan to take the USMLE. Clinical clerks function as full members

of the managing ward team but have less responsibilities for their

patients; they may not write orders. Ideally these clinical clerks

will return to Japan wanting improvements in their medical educational

system.

On a related topic, I am frequently asked by medical students

visiting Kameda Medical Center to explain the differences and

advantages of the American system of medical education., in two

minutes or less. One the one hand, I tell them there is no advantage

for them to aspire American residency training. This is because

the Japanese medical education is a complete system, with training

and life-long career practice relatively comfortable for the Japanese

practioner. The Japanese health care system is focused on the

physician in a paternalistic manner. Conformity to the group norms

makes for a comfortable, stable practice environment, without

threat of malpractice from irate patients. The Japanese educational

framework from primary school through graduate education fosters

discipline and obedience to authority; individuality and creative

thinking are either discouraged or not overtly encouraged. On

the other hand, the rigors of precise clinical problem solving

skills are sub-optimal, errors in patient management are relatively

frequent, harm to patients is overlooked without criticism or

feedback to the practioner, medical chart work poorly documented,

all resulting in many instances of both over and under treatment.

Some exceptional medical students and residents intrinsically

recognize this dilemma and desire change and improvements.

The American system of medical education has been know for its

openness to group discussions, sharing of ideas regardless of

position or status and dedicated focus on the patient. Evidenced-based

clinical decisions have power over personal opinions, even those

of the professor. Accountability and a vigorous system of checks

and balances enforces the patient- centered practice milieu. Problem

solving skills and creative thinking are introduced in primary

schools and enhanced throughout the maturation of the competent

clinician. American medical practice requires a balance between

the science of medicine(evidence-based data) and the art of

medicine(caring

and biomedical ethics). These listed advantages of the American

system must be understood in the context of disadvantages. For

example any physician may make a mistake. However, such errors

in clinical judgment may bring stiff penalties in my country.

The freedoms of independence and clinical practice are being limited

these days by the necessities of curtailing the enormous national

health care expenditure, currently 13-14% of gross domestic product

(compared to about 7% in Japan). These limits are already impacting

on postgraduate medical education in ways that are partially

detrimental

to residency training. Decreased length of hospital stay for in-patient

care decreases total costs at the expense of decreasing the educational

training benefits to residents. Residents are becoming mere overworked

data managers with little time to think about and discuss their

patients' problems. Managed care forces residents to attend to

greater number of patients each day and week without comprehensive

care for their needs. The prior years training balance between

education and labor is shifting toward decreasing educational

efforts and increasing toil. To add further difficulties to the

burdensome resident's life, training programs are reducing the

number of available residency positions while increasing the patient

load. These reductions are occurring because of an over-supply

of physicians. The brunt of these reductions will occur with

international

medical graduates(IMG) seeking training in America. Hence the

opportunities for IMG to obtain American residencies are being

restricted currently with greater limits planned for the future.

Because of the perceived successful Japanese medical educational

system by Japanese, and because of the generally low level of

English language speaking

skills, they have made up a very small percent of IMG in America.

The largest numbers of IMG are from India(20%), Pakistan(12%)

and the Philippines(9%). Japan is not among the top 10 countries

having participants in American postgraduate clinical training

programs.

In considering these advantages and disadvantages in the American

system, Japanese young physicians should understand that no system

is perfect, each has benefits and detriments. Yes, I clearly find

many advantages to the Japanese system, as for example, its gentleness

to colleagues, its forgiveness for physician errors and the security

of its ikyoku system. But overall, there is no doubt in my mind

of the superiority of the American medical educational system.

Fortunately there exists a small but highly dedicated group of

serious minded bright Japanese medical students, residents and

senior physicians wanting to improve this deficient state of medical

training and practice in Japan. It is to this small determined

group that I devote my energies to support and encourage their

struggles to understand analytic problem solving skills, the foundation

of Western medical practice. For the average resident I help train

at Kameda Medical Center, I do not encourage them to study in

American., for the reasons stated above. Rather it is my hope

that through exposure to the American system as exemplified by

NMRI's successful medical exchange programs(both subinternships

and clinical clerkships), select Japanese national medical education

leaders, contact with me and similar Western trained medical educators,

a growing number of physicians will have increasing influence

to modify the tradition - bound restrictions inhibiting the proper

development of clinical training and practice in Japan. These

necessary modernization modifications include the field of biomedical

ethics as well. The international medical communities have agreed

that informed consent requires the end of the paternalistic physician

role, supplanted by the decision control vested in the patient's

(or his/her surrogate ) informed consent to all management and

treatment issues.

For a financially rich and developed county as Japan clearly is,

with its internationally acclaimed automotive and electronics

industries, its medical education and heath care practices are

well below Western standards. I predict the aging of the population

will force changes which I can only hope will improve clinical

practice. The Japanese people deserve better care than is currently

available. NMRI should be one of the national organizations leading

improvements in Japanese health care into the 21st century.

5 Stein, G.H.:Physical examination (PE) skills of first year residents. Proceeding:The 29th Japan Medical Education Society Meeting in Kanazawa,Japan, (July 1997).

ABSTRACT

Physical examination (PE) skills of PGY 1 Gerald

H. Stein, MD, FACP

Kameda Medical Center (KMC), Kamogawa City, Chiba Ken

[Object] Graduating medical students are assumed to have clinical

skills to perform an adequate PE upon entering the first year

of residency. The object of this study was to measure the quantitative

PE skills of entering first year residents and compare their scores

after completing 6 months of internal medicine rotations.

[Project design] All entering first year residents starting a

2 year super rotation at a non-university community teaching hospital

were invited to participate in the project. During the 1st to

2nd weeks in May, each resident performed a PE on one patient

within a 30 minute time limit. I observed each resident's PE,

checking off each of 45/47 (difference is breast PE in women)

items from a list as the resident performed the task. I modified

the check-list which I had used at the University of Florida (UF).

It is routinely used throughout American medical schools. The

original list contained 78 items. During the first year of the

study I standardized the check list to 45/47 items. In addition

to the pre-test during orientation, each 1st year resident received

a post- test at the end of the 6 month medicine rotation. The

post test occurred at 6 months for half of the residents and at

12 months for the other half.

[Results]For all the 22 residents(9 public medical schools 1 city

and 8 private ), the pre test scores were 11 to 30, with an average

score of 20 or 44 % correct. The post test scores were 27 to 44

with an average score of 38 or 82 % correct. The study was conducted

over 3 years. There was no apparent differences in the scores

between the 3 classes starting, 1994, 1995 and 1996. The 22 residents

used 55 % of the allotted time for the pre test and 78 % of the

allotted time for the post test.

[Discussion] Overall, graduating medical students performed less

than 50% of items on a simplified check list. The post internal

medicine rotation scores were about 82 %, indicating improvement

but suggestive of marginal clinical skills. Comparison score from

UF are 90 % required to pass; 0-2 failures/year. Possible reasons

for low proficiency include anxiety from being observed doing

PE first time, not using allotted time, and small sample size.

The KMC tests were scored for quantitative measures. Qualitative

assessment was not systametically evaluated. However I observed

most entering residents had poor techniques of percussion, palpation,

and auscultation. The order of the examination was often erratic.

[Conclusion] Japanese first year residents' PE skills are of

questionable

proficiency. Japanese medical educators might consider the significance

of these findings.

Physical Examination Skills

Objectives

1. Development of quantatative 'check-list'

for physical examination of internal

medicine in-patients by first year residents

2. Measurement of physical examination skills

of entering first year super-rotation

residents

3. Comparison of their scores after 6 months of internal medicine rotations.

Physical Examination Skills

Project Design

1. Modification of physical examination check-list,

from a standardized list used at the

University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida, USA. A similar list

is routinely used

throughout American medical schools to assess second year medical

students.

A. Reduction from 78 items to 45 or 47 items(difference is breast

examination in women)

B. First year development, standardizing, and testing of check-list.

This data

omitted from analysis since check-list frequently modified and

pattern of

scoring inconsistent.

2. Site of tests was Kameda Medical Center,

a 800 bed non-university private

community teaching hospital serving a rural community.

3. Subjects were entering first year residents of a 2 year super-rotation program.

4. Physical examinations were performed on

internal medicine cooperative in-patients,

within an announced 30 minute time limit, during the first to

second weeks in May for

the years 1994, 1995 and 1996. This was the pre-test.

5. I observed each resident's physical examination

in silence, checking off each of the

45 or 47 items as they were done, noting the starting and ending

times plus any

comments about the resident's performance.

6. Immediately after the test, I showed each

resident their check-list and explained

their deficiencies; also each resident received a photo-copy of

their check-list as

well as a copy of the University of Florida outline for physical

examination.

7. Each first year resident performed a repeat

physical examination check-list at the

end of the 6 month medical rotation. This is called the post-test.

The post-test was

similar to the pre-test in every way, except that the resident

choose the patient for

the check-list examination. The post-test occurred at the end

of the first 6 months for

half of the residents and at 12 months for the other half.

Physical Examination Skills

Results

I. Residents' characteristics

A. Number completing pre-test and post-test 22

(number not completing pre-test and post-test 2)

B. Age ~25

C. Sex 17 men, 5 women

D. Medical Schools 18 : 9 national, 1 city, 8 private

II. Quantatative results from check-list scores

A. Pre-test - Number of items checked

1994(n = 9) Mean 21 items (range 11- 30), or 47%

1995(n = 5) Mean 20 items (range 15 - 26), or 43%

1996(n = 8) Mean 20 items (range 13 - 30), or 42%(more female

breast exams)

B. Post-test - Number of items checked

1994(n = 9) Mean 37 items (range 28 - 44), or 84%

1995(n = 5) Mean 34 items (range 27 - 40), or 75%

1996(n = 8) Mean 39 items (range 34 - 44), or 85%

C. Total Pre-test (n = 22) Number of items checked Mean 20 items, or 44%

D. Total Post-test (n = 22) Number of items checked Mean 38 items, or 82%

E. Total Pre-test time used 16 minutes, or 55% of allotted time

F. Total Post-test time used 24 minutes, or 78% of allotted time

III. Qualitative impressions

A. Order of examination : Pre-test often erratic, Post-test improved

B. Technique : Pre-test often primitive percussion,

palpation and auscultation; Post-

test improved

D. Communication with patient : Pre-test poor, Post-test excellent

C. Frequently missed items : Pre-test many,

Post-test respiration rate, visual acuity,

ophthalmoscopy, hearing, otoscopy, breast(women), joints, mental

status,

coordination and gait

Physical Examination Skills

Comments

I. Recent medical school graduates(first year

junior residents) completed less than

50% of items while observed performing a physical examination

on adult in-patients.

2. After 6 months of internal medicine rotations, the first year

residents completed 82%

of items while observed performing a physician examination.

3. Although qualitative components were not systematically recorded,

most entering

residents had poor techniques of percussion, palpation, and

auscultation.

Post-test

techniques greatly improved.

4. Possible reasons for low scores during the pre-test

a. Inadequate training and practice in medical schools

b. Anxiety in performing physical examination observed by foreign

physician

c. Failure to use the allotted time

d. Small sample size, sampling errors, and bias of observer

e. PE check list not suitable for Japanese medical students and

residents

5. Possible reasons for improved scores during the post-test

a. Training and practice during internal medicine rotations

b. Using more of the allotted time

c. Studying the check list immediately before the post-test

d. Small sample size, sampling errors, and bias of observer

6. Comparisons with other Japanese residents: unknown

7. Comparison with American medical students not possible because

of major

differences in training and testing

8. Data from American medical schools for interest purposes only

a. University of Florida, Gainesville, requires 90% completion

of a 78 item check list

to pass the course; 0-2 fail each year ( 3 of 22 Kameda residents

had post- test

scores > 90% )

b. University of Hawaii, Honolulu, requires 95% completion of

a similar check list to

pass the course; none fail ( 1 of 22 Kameda residents had post

test scores > 95%)

Physical Examination Skills

Reflections

1. Japanese first year residents' physical examination skills are of questionable proficiency. Is this conclusion justified?

2. Japanese medical educators might want to replicate this study. If these finding are confirmed, Japanese medical educators might consider the significance of these finding. They also might want to consider improvements in the teaching of physical examination skills either in medical school, or in residencies.

3. Japanese medical educators further might consider detailed analysis of the skills of medical school graduates to perform a complete medical history, assessment and plan, the other components of clinical skills evaluation.

4. Although this audience is committed to improving medical students' clinical skills, perhaps the focus should be on ways to change medical school curriculum.

6. Stein, G.H.: Ideal skills for junior residents(JR). Proceeding: The 29th Japan Medical Education Society Meeting, Kanazawa, Japan, (July 1997).

Abstract

Ideal skills for Junior residents(JR)

Gerald H. Stein, MD, FACP

Kameda Medical Center (KMC), Kamogawa City, Chiba Ken

Ideal clinical skills for junior residents

include:

1. Development of the basic clinical skills for creative thinking

and solving clinical problems.

2. Integration of basic sciences of human diseases with clinical

medicine.

3. Interactions with senior residents, staff physicians, consultants

and department chiefs.

4. Learning to use medical literature search for clinical decisions:

evidenced-based medicine.

5. The development of life-long learning patterns.

6. Participation in peer review and quality assurance.

7. Community ethical focus.

Medical educators can teach the small steps

for JR to learn Problem Oriented System by insisting on a complete

listing of all problem and grouping the problems together to make

the assessments with a full differential diagnosis. The plan of

clinical studies follows logically from the assessment; no plan

is written without an assessment. The plan of treatment also follows

from the assessment. Teaching is done in small groups of JRs by

a detailed review of each entry into the patient's medical record,

with bedside visits to clarify history, expand review of systems

and demonstrate physical finding. Progress notes are similarly

fully discussed using the SOAP format. As the patient's hospital

course evolves, other skills are slowly introduced during chart

daily rounds. JR are encouraged to recall basic science components.

Differences of opinion between junior and senior residents, between

JR are consultants, between JR and attending physicians are encouraged

with proper evidence-based support from the medical literature.

Ethical issues such as Do-Not-Resusitate, informed consent, openness

with patients and their family about the illness are reviewed

as the clinical situation arises.

Examples from my teaching rounds will illustrate these points.

Conclusion: Medical educators and hospitals with JR programs might

want to study their goals. Such discussions might be helpful in

improving the clinical training programs in Japanese hospitals.

1. Development of the basic clinical skills

for creative thinking and solving

clinical problems

a. Problem Oriented System(POS)/ Subjective

Objective Assessment

Plan(SOAP) : Teaching in small groups by detailed review of each

entry

into the patients medical chart, with bedside visits to clarify

history,

expand review of systems(ROS) and demonstrate physical findings

b. Example of 1st year junior resident's medical

chart: 1st month

c. Example of 1st year junior resident's medical chart: 12th month

2. Integration of basic sciences of human diseases

with clinical medicine:

small group discussions with review articles

3. Interactions with senior residents, staff

physicians, consultants and

department chiefs: small group discussions

4. Learning to use medical literature for evidence-

based clinical decisions:

from library(books, journals, CD-ROM, Internet) to bedside

5. The development of life-long learning patterns:

attending physician as

role model

6. Participation in peer review and quality

assurance: quality improvement

by review of the residents own medical chart in small groups

7. Community ethical focus: small group discussions

as topic presents itself

from resident's patient.

Other manuscripts

7. Stein, Gerald H., Creative Thinking-Clinical Problem Solving Resident Physician Training program Kameda Medical Center. Japan Hospitals No 14, July 1995: 35-37.[Photocopy on request]

8. Stein, G.H., Clinical Rounds. URL: http://www2.gol.com/users/kmcdoc/; 1996-1999 [Photocopy on request]