Shot Description

Shot 1

2:15:46

5 seconds

- The crowds chant "Maximus!" repeatedly.

- Non-diegetic orchestral music, composed mainly of string instruments, plays at a low volume.

- The camera starts in a high-angle medium shot of the crowd, pans right, and then tilts left for a long shot of the extended Colosseum crowd echoing the chant.

Shot 2

2:15:51

11 seconds

- Cut to an eye-level medium shot of the aristocratic group sitting on a balcony and talking.

- The camera pans left and tracks backward to show the crowds in the background on the opposite side of the stadium.

- The music continues in the same style through the entire scene.

- The chanting continues, at a decreased volume until shot 7.

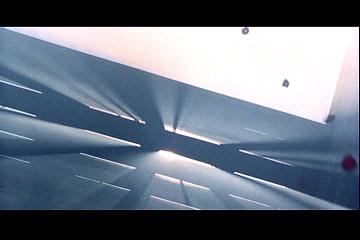

Shot 3

2:16:02

5 seconds

- Cut to an overhead medium tracking shot of Maximus in chains, viewed through the rafters that seem to lead up to the stadium, the source of the crowds that chant his name.

Shot 4

2:16:07

3 seconds

- Cut to a medium shot of Commodus, who enters through the gates as the camera zooms out slowly to accomodate him in the frame.

Shot 5

2:16:10

7 seconds

- Cut to the other gladiators, with which Maximus has shared battles, shot in close-up behind bars. Their eyes follow Commodus as he walks by them.

- The camera pans right, and stops on Juba, the man that was partnered with Maximus since he became a gladiator.

Shot 6

2:16:17

3 seconds

- Cut to Gracchus, who also looks at Commodus, as the camera continues to slowly pan right.

Shot 7

2:16:20

15 seconds

- Cut to Commodus, who glances up at the "Maximus" chants and looks at him, still chained to the walls.

- The camera tilts up and frames Commodus over his left shoulder.

- Commodus repeats the crowd's chant in a near-whisper.

Commodus's entrance and identification with the "Maximus" chants recalls a previous scene where Maximus succeeds in the arena as a gladiator and is able to reveal his identity to the emperor. The combination of these two key scenes is a distinct re-writing of the famous scene in Ben Hur where Judah walks out from an obscuring darkness. Both films generate this turning point to reveal to the antagonist that his friend-turned-enemy is alive and seeking vengeance. Maximus picks up an arrow tip in the sand as Commodus first approaches him, subtly alluding to Judah's presentation of a knife to Messala.

Shot 8

2:16:35

10 seconds

- Cut to Maximus, framed over the shoulder of Commodus. This is a standard reverse shot maintaining the rules of continuity filmmaking. The following 14 shots cut back and forth like the previous two with respect to the character positioning, with Maximus always on the right side of the shot in close-up.

- Commodus tells him "They call for you." The previous chanting is significantly lower in volume, presumably because they are closed off or further from the crowd.

Shot 9

2:16:45

10 seconds

- Reverse shot of Commodus. He calls Maximus "the general who became a slave, the slave who became a gladiator, the gladiation who defied an emperor; a striking story."

- The crowd chants are almost completely obscured by the background music and talking.

This script recalls the popular rhetoric of epic cinema. Hyperbole and exaggeration are generally the dominant literary techniques used in epic films. The all-encompassing and glorifying titles and taglines of epics have included The Greatest Story Ever Told, "His passion captivated a woman. His courage inspired a nation. His heart defied a king," and "The splendor and savagery of the world's wickedest empire! Three hours of spectacle you'll remember for a lifetime!" His comment that it makes for a striking story hints at the self-reflexivity presented in Roman epic film, that the gladiatorial combat and political processions are historical analogs of the epic film. The decadence and excitement sustain the "striking story" to draw modern crowds. Not coincidentally, this dialogue was Gladiator's main tagline and featured prominently in trailers and teaser previews.

Shot 10

2:16:55

9 seconds

- Reverse shot of Maximus. Commodus continues, saying "...and now the people want to know how the story ends. Only a famous death will do."

Continuing with the assumption from the previous shot, Commodus is negotiating the terrain of the historian and critic. The diegetic referrent is the same as the director's concerns: to create a captivating story within the epic formula. He also echoes the desires of the viewer, who historically recognizes epics in chronicle form (a series of chronological events connected by a common thread [i.e. the hero's life]) and yearns for a decisive conclusion.

Shot 11

2:17:04

3 seconds

- Reverse shot of Commodus. He extends his hand towards Maximus's face.

Shot 12

2:17:07

3 seconds

- Reverse shot of Maximus. Commodus says "...and what could be more glorious..."

Shot 13

2:17:10

3 seconds

- Reverse shot of Commodus. Commodus says "...than to challenge the emperor himself in the great arena."

Shot 14

2:17:13

6 seconds

- Reverse shot of Maximus, who asks "You would fight me?" Commodus replies "Why not?"

Shot 15

2:17:19

3 seconds

- Reverse shot of Commodus, who asks "Do you think I'm afraid?"

Shot 16

2:17:22

4 seconds

- Reverse shot of Maximus, who responds "I think you've been afraid all your life."

Shot 17

2:17:26

4 seconds

- Reverse shot of Commodus, who retorts "Unlike Maximus the invincible, who knows no fear?"

Again, the dialogue is playing off of similar tropes in other epic films. The epic protagonist is generally elevated to mythic or superhuman level through the legend and lore that accompanies their stories. For example, William Wallace and Alexander the Great occupy immense historical positions in the image of Jesus Christ, perhaps the ultimate epic figure due to the connotations his name carries.

Shot 18

2:17:30

13 seconds

- Reverse shot of Maximus, who smirks at his remark and replies "I knew a man who once said 'Death smiles at us all; all a man can do is smile back.'"

Shot 19

2:17:43

6 seconds

- Reverse shot of Commodus, who says "I wonder, did your friend smile at his own death?"

Shot 20

2:17:49

6 seconds

- Reverse shot of Maximus, who replies "You must know. He was your father."

Shot 21

2:17:55

7 seconds

- Reverse shot of Commodus, who grimaces and says "You loved my father, I know. But so did I. That makes us brothers, doesn't it?"

This shot is the exact halfway point of the scene. For the attentive and knowledgeable viewer, it recalls the myth of Rome's founding. Historical legend tells of two brothers who were abandoned at birth and raised by a wolf. Romulus slays his brother Remus to become the first king of Rome. This is the second foreshadowing of Maximus's death.

Shot 22

2:18:08

3 seconds

- Reverse shot of Maximus. Commodus reaches forward to embrace him.

Commodus's embrace is the third foreshadowing of Maximus's death. His similar affection to his father early in the film leads to his smothering death. This is the only other time in the film that Commodus is this close to another man. Maximus's relationship with Lucilla threatens Commodus earlier in the film, and this scene is just after he learns of her alliance with him.

Shot 23

2:18:11

2 seconds

- Reverse shot of Commodus, who says "Smile for me now, brother."

This shot disrupts the rhythmic harmony that is set up in the previous 16 cuts. The repetitive continuity that places Commodus on the left side of the shot is reversed when he crosses Maximus. This dystopic change in orientation, by intentionally breaking the stringent layout, is the fourth foreshadowing of Maximus's death. The decision to have Commodus come to the right side is a calculated movement that heightens the tension and adds to the disorientation of the next 4 cuts, which are all 1 second apart.

Shot 24

2:18:13

1 second

- An extreme close-up shot, Commodus bring his hand around and stabs Maximus in the back.

- The music continues, with an added effect of deep and loud wind that highlights the stabbing. An exaggerated squishing / metallic sound is audible.

Shot 25

2:18:14

1 second

- Cut back to Maximus in close-up, who groans in pain.

Shot 26

2:18:15

1 second

- Cut back to the stab wound. Commodus removes the knife and blood drips from the wound.

Shot 27

2:18:16

1 second

- Cut back to Commodus in close-up. He kisses Maximus on the face.

Shot 28

2:18:17

3 seconds

- Reverse shot of Commodus in close-up.

- He turns around to face away from Maximus and looks towards a space that has not yet been identified by the camera and says "Strap on his armor."

Shot 29

2:18:20

2 seconds

- Cut to Quintus, who is clearly receiving Commodus's command. Commodus says "Conceal the wound."

Shot 30

2:18:22

3 seconds

- Cut back to Commodus from behind.

- The shot is in slow motion, running at approximately 8 frames per second.

- Commodus turns around and looks at Maximus.

Shot 31

2:18:25

3 seconds

- Reverse shot of Maximus, who lifts his head to see Commodus.

Shot 32

2:18:28

5 seconds

- Cut back to the external shot, composed with the crowd of fans, apparently still cheering "Maximus," in long shot filling up frame's background.

- The camera pans left to show Lucilla and Lucius close-up in the foreground.

Shot 33

2:18:33

2 seconds

- Cut to a medium shot of the gates from directly below. They open up to the ground-level of the Colosseum. As they open, the sunlight flares the image from dark gray to white.

Shot 34

2:18:35

4 seconds

- Cut to the platform under the gates in medium shot.

- The camera remains stationary as the platform rises vertically. Maximus tilts his head down and Commodus gazes upwards.

- Deep operatic chanting is audible in the music.

Shot 35

2:18:39

2 seconds

- Cut back to the gates from below. Flower petals fall down onto the platform as the gates slide open.

Shot 36

2:18:41

1 second

- Cut back to the platform, where Quintus, Maximus, and Commodus stand surrounded by Roman guards.

- The same slow upward motion is consistent through the end of the scene.

Shot 37

2:18:42

2 seconds

- Cut to a close-up of Maximus, standing in dark armor and looking down.

Shot 38

2:18:44

2 seconds

- Cut to a close-up of Commodus, standing in an ornate white armor and looking up.

Shot 39

2:18:46

3 seconds

- Cut back to the gates, which slide all the way open.

Shot 40

2:18:49

5 seconds

- Cut back to the platform in medium shot. The camera zooms out to a long shot of the platform slowly raising.

Shot 41

2:18:54

12 seconds

Shot 41

Continued

2:19:05

- Cut back to an extreme long shot of the Colosseum crowd.

- The camera begins on the right side and pans left to the center of the arena, where the platform is just breaking ground level.

- The guards are in a formation around Quintus, Maximus, and Commodus.

- The same music continues, but the crowd is no longer cheering anything.