Week 2: Unit 1

28/08/11 15:53

This week we’ll be looking at Greek nouns (people, places and things in case you don’t quite remember elementary English grammar).

Greek Nouns

Greek nouns must be one of three genders: masculine, feminine and neuter. These are grammatical categories: they don’t have any relation to the male or female sexual gender as most nouns are arbitrarily classified as masculine, feminine or neuter.

Greek nouns also can be expressed in three numbers: singular, plural and dual. These should be a little more familiar, since English at least has the singular and plural numbers. Nouns in the dual are for people, places and things thought of in pairs (these are thankfully rare).

Finally, Greek nouns have case. Case explains the function of a noun within a sentence. In English, we know the function of a given noun by the order in which the sentence was organized, but word order did not develop as an essential aspect of Ancient Greek - hence nouns had to be reclassified with special endings whether they were acting as subject, direct object or indirect object, etc. For a quick overview:

The dog eats the popsicle. --- ‘Dog’ is the subject here (it’s performing the action of the verb) and ‘popsicle’ is the direct object (it’s receiving the action of the verb - it’s being eaten).

The tiger delivers the popsicle to the dog. --- Here ‘tiger’ is the subject (again, it’s performing the action) and ‘popsicle’ is the direct object (it’s receiving the action - it’s being delivered). The ‘dog’ is the indirect object, it is directly affected by the action of the verb, but does not receive that action).

Word order and the use of prepositional phrases (‘to the dog’) told us the when the tiger was the subject and when the dog was the indirect object, but since the Greeks did not observe strict word order - they had to assign special endings to nouns in order to distinguish subject, direct object and indirect object.

Thus all Greek nouns will be divided into a stem which retains the base meaning of the word, and an ending, which shows the number and case of the word. Gender is fixed for each noun and must be memorized.

Greek Cases

Greek is actually simplified from other Indo-European languages (such as Latin) in that it only has five cases. Because of this simplification, however, some cases will perform multiple functions.

The Nominative Case: This case was used to identify the subject of a sentence, or a predicate nominative: ‘That guy flies airplanes’ (the subject is that guy, and in Greek, would be in the nominative). ‘That guy is a pilot’ (‘pilot’ is said to be a predicate nominative because it is simply equated with the subject, ‘guy,’ and thus in Greek both the subject and the predicate nominative would be in the nominative case).

The Genitive Case: This case simply made one noun into an adjective to modify another. In English, we can do the same thing with the preposition ‘of’ which should be your go-to translation for this case. Examples include ‘the man of steel,’ or ‘the father of our country.’ In Greek, no preposition would be used: instead ‘steel’ and ‘country’ would be in the Genitive case.

This case is also used to show motion away from, expressed in English with the prepositions from or out of.

The Dative Case: This case provided the Greek indirect object (essentially something affected by the action of the verb but not actually receiving that action). In our language, the prepositions to and for provide the function of the dative case. The dative can also be used to show means or instrumentality, basically by what means something was accomplished (I hit the giant spider with a baseball bat; I wrote my will with an old-timey feather pin) or accompaniment (I picked blueberries with my imaginary friends). Constructions of place where and time when are also in the dative: ‘in the park’ or ‘at three o’clock.’

The Accusative Case: This case indicated which noun acted as the direct object (the ‘popsicle’ from the examples above). It also could show motion towards or a length of time: ‘to Greece’ or ‘for six months.’

Finally, the Vocative Case simply indicated direct address. Whenever you talk to someone/something, that person/thing must appear with a special vocative case ending: ‘Hey Caesar, you’ve got red on your toga.’

The Declension of Nouns

Each Greek noun will have a special ending for each case, with variations for singular and plural (remember gender is fixed for each noun). In the vocabulary, you’ll see the first two entries for the noun, followed by the definite article (we’ll get to that later). The article tells you what gender the noun is, and the first two entries tell you how the other endings will appear/be attached to the stem of the noun. These two entries are the nominative singular and the genitive singular, and you would do well to memorize them - they are required (along with the article) for every vocabulary quiz we take. Let’s look at an example:

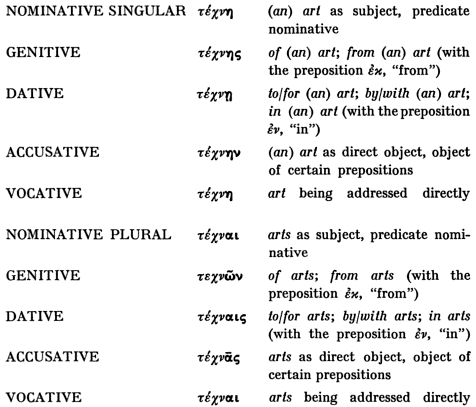

τέχνη, τέχνης ἡ. τέχνη = the nominative singular, τέχνης = the genitive singular and ἡ is the feminine definite article (it just means ‘the’). after τέχνη, τέχνης ἡ, you’ll see the definition of the word in English.

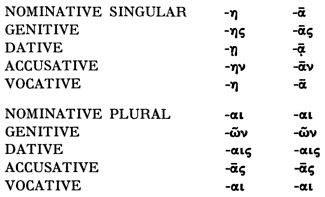

The First Declension

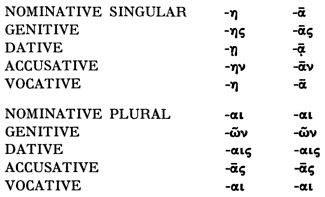

Greek nouns belong to one of three declensions, that is, patterns of endings to be applied to the stem based on what case you need to use in a particular sentence. Nouns can only belong to one declension. Let’s look at the first declension, sometimes called the α-declension, whose endings mostly use the vowels -η- and a long -α-. It’s worth noting now that all nouns of the first declension with -η- and a long -α- are feminine:

(The charts are pulled directly from your text-book. Check there for a more in-depth analysis of the case functions, as well as the special rules for accentuation in the first declension.)

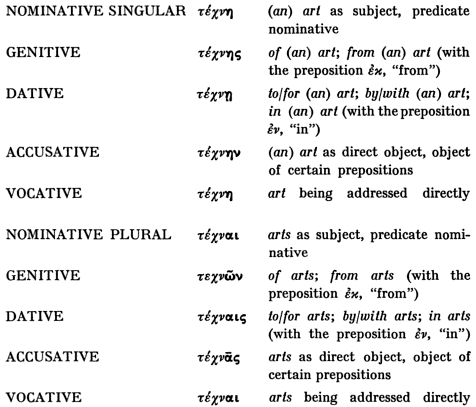

To decline τέχνη, we’ll just take the ending off the genitive singular form (τέχνης, given by the dictionary entry and memorized by all good Greek students), leaving us with τεχν- and and from there simply add on the endings listed above:

The Second Declension

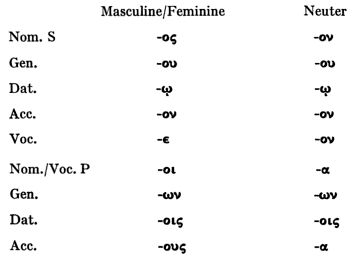

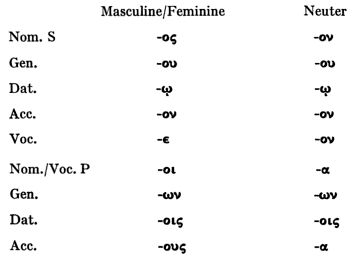

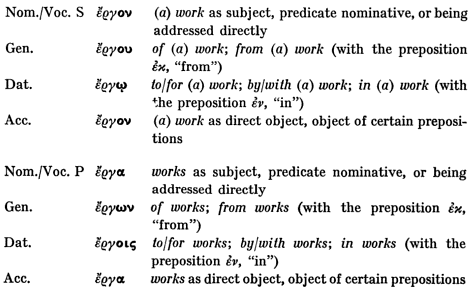

The second declension contains some nouns ending in -ος (mostly masculine and some feminine) and some nouns ending in -ον (neuters). It is declined as follows:

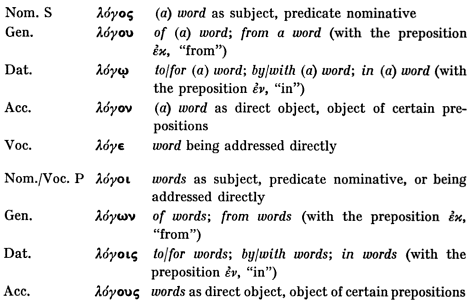

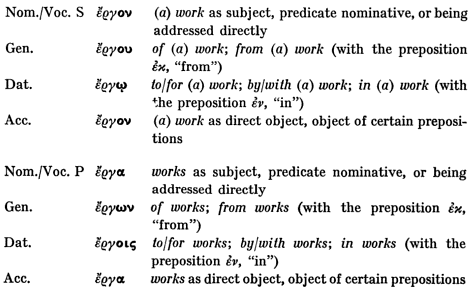

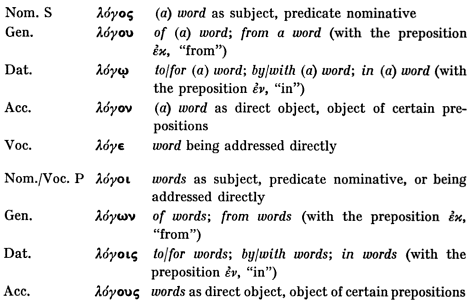

Again, in order to decline a second declension noun, we will simply remove the ending of the genitive singular form (say, from the masculine noun λὀγος, λὀγου, ὁ or the neuter noun ἔργον, ἔργου, τό) thus leaving us with λογ- (or εργ-). Next, all we have to do is attach the appropriate endings for each case. The end result should look something like this:

(Again, be sure to check Hansen and Quinn for special rules concerning accentuation.)

The Article

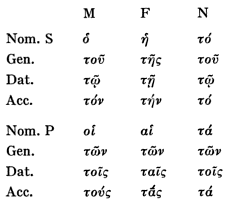

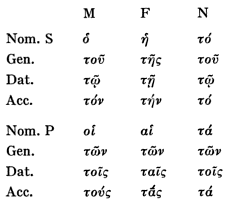

Greek has a definite article (‘the’ in English) but no indefinite article (‘a’ or ‘an’ in English). The definite article must be formed so as to match the gender, number, and case of the noun it governs:

(M, F and N refer to masculine, feminine and neuter, respectively. This chart, like those above, was pulled from Hansen and Quinn and must be memorized!)

An easy tool for accent memorization: note that the genitive and dative always receive a circumflex, but not other case does. Every other accent is acute, except for the masculine and feminine singular and plural, which receive not accent, only a rough breathing.

Thus ὁ will never be paired with τέχνη and ἡ will never be paired with λόγος, because those articles do not agree with their nouns in gender (ὁ is masculine and ἡ is feminine).

Attributive Position

When the Greeks wanted to modify a noun, they would often place all of the modifiers for a specific noun between the article and the noun. Although we do this in English with most adjectives (‘the delicious ice cream), in Greek all modifiers could be put in this order: genitives (the ‘of the bank’ money, rather than ‘the money of the bank,’ or simply ‘the bank’s money’), prepositional phrases (the ‘under the deck’ beehive), etc. When modifiers (genitives, adjectives and prepositional phrases) are arrayed like this between the article and the noun they refer to, they are said to be in attributive position.

ὁ σοφὸς ἀνήρ - the wise man.

ὁ τοῦ πατρὸς βιβλίον - the ‘of the father’ book, i.e. ‘the book of the father.’

οἱ ὲν τῇ χὠρᾳ ἀδελφοί - the ‘in the country’ brothers, i.e. ‘the brothers in the country’ or ‘the brothers who happen to be in the country.’

Sometimes the article is simply repeated with the modifiers placed after it:

ὁ ἀνὴρ ὁ σοφός - ‘the man, the wise one.’

τὸ βιβλίον τὸ τοῦ πατός - ‘the book, the one that belongs to father.’

οἱ ἀδελφοὶ οἱ ἐν τῇ χώρᾳ - ‘the brothers, the ones in the country.’

And sometimes the Greeks got lazy and just ditched the article before the noun altogether:

ἀνὴρ ὁ σοφός

βιβλίον τὸ τοῦ πατός

ἀδελφοὶ οἱ ἐν τῇ χώρᾳ

All of these constructions are said to use modifiers in the attributive position.

That’s pretty much it! Check sections 16.4 and 17 (pgs. 29 - 30) for some notes on the use of the article (the Greeks used the definite article a lot more than we do) and word order (Subject-Object-Verb is most popular, but it essentially did not matter, aside from attributive position).

Greek Nouns

Greek nouns must be one of three genders: masculine, feminine and neuter. These are grammatical categories: they don’t have any relation to the male or female sexual gender as most nouns are arbitrarily classified as masculine, feminine or neuter.

Greek nouns also can be expressed in three numbers: singular, plural and dual. These should be a little more familiar, since English at least has the singular and plural numbers. Nouns in the dual are for people, places and things thought of in pairs (these are thankfully rare).

Finally, Greek nouns have case. Case explains the function of a noun within a sentence. In English, we know the function of a given noun by the order in which the sentence was organized, but word order did not develop as an essential aspect of Ancient Greek - hence nouns had to be reclassified with special endings whether they were acting as subject, direct object or indirect object, etc. For a quick overview:

The dog eats the popsicle. --- ‘Dog’ is the subject here (it’s performing the action of the verb) and ‘popsicle’ is the direct object (it’s receiving the action of the verb - it’s being eaten).

The tiger delivers the popsicle to the dog. --- Here ‘tiger’ is the subject (again, it’s performing the action) and ‘popsicle’ is the direct object (it’s receiving the action - it’s being delivered). The ‘dog’ is the indirect object, it is directly affected by the action of the verb, but does not receive that action).

Word order and the use of prepositional phrases (‘to the dog’) told us the when the tiger was the subject and when the dog was the indirect object, but since the Greeks did not observe strict word order - they had to assign special endings to nouns in order to distinguish subject, direct object and indirect object.

Thus all Greek nouns will be divided into a stem which retains the base meaning of the word, and an ending, which shows the number and case of the word. Gender is fixed for each noun and must be memorized.

Greek Cases

Greek is actually simplified from other Indo-European languages (such as Latin) in that it only has five cases. Because of this simplification, however, some cases will perform multiple functions.

The Nominative Case: This case was used to identify the subject of a sentence, or a predicate nominative: ‘That guy flies airplanes’ (the subject is that guy, and in Greek, would be in the nominative). ‘That guy is a pilot’ (‘pilot’ is said to be a predicate nominative because it is simply equated with the subject, ‘guy,’ and thus in Greek both the subject and the predicate nominative would be in the nominative case).

The Genitive Case: This case simply made one noun into an adjective to modify another. In English, we can do the same thing with the preposition ‘of’ which should be your go-to translation for this case. Examples include ‘the man of steel,’ or ‘the father of our country.’ In Greek, no preposition would be used: instead ‘steel’ and ‘country’ would be in the Genitive case.

This case is also used to show motion away from, expressed in English with the prepositions from or out of.

The Dative Case: This case provided the Greek indirect object (essentially something affected by the action of the verb but not actually receiving that action). In our language, the prepositions to and for provide the function of the dative case. The dative can also be used to show means or instrumentality, basically by what means something was accomplished (I hit the giant spider with a baseball bat; I wrote my will with an old-timey feather pin) or accompaniment (I picked blueberries with my imaginary friends). Constructions of place where and time when are also in the dative: ‘in the park’ or ‘at three o’clock.’

The Accusative Case: This case indicated which noun acted as the direct object (the ‘popsicle’ from the examples above). It also could show motion towards or a length of time: ‘to Greece’ or ‘for six months.’

Finally, the Vocative Case simply indicated direct address. Whenever you talk to someone/something, that person/thing must appear with a special vocative case ending: ‘Hey Caesar, you’ve got red on your toga.’

The Declension of Nouns

Each Greek noun will have a special ending for each case, with variations for singular and plural (remember gender is fixed for each noun). In the vocabulary, you’ll see the first two entries for the noun, followed by the definite article (we’ll get to that later). The article tells you what gender the noun is, and the first two entries tell you how the other endings will appear/be attached to the stem of the noun. These two entries are the nominative singular and the genitive singular, and you would do well to memorize them - they are required (along with the article) for every vocabulary quiz we take. Let’s look at an example:

τέχνη, τέχνης ἡ. τέχνη = the nominative singular, τέχνης = the genitive singular and ἡ is the feminine definite article (it just means ‘the’). after τέχνη, τέχνης ἡ, you’ll see the definition of the word in English.

The First Declension

Greek nouns belong to one of three declensions, that is, patterns of endings to be applied to the stem based on what case you need to use in a particular sentence. Nouns can only belong to one declension. Let’s look at the first declension, sometimes called the α-declension, whose endings mostly use the vowels -η- and a long -α-. It’s worth noting now that all nouns of the first declension with -η- and a long -α- are feminine:

(The charts are pulled directly from your text-book. Check there for a more in-depth analysis of the case functions, as well as the special rules for accentuation in the first declension.)

To decline τέχνη, we’ll just take the ending off the genitive singular form (τέχνης, given by the dictionary entry and memorized by all good Greek students), leaving us with τεχν- and and from there simply add on the endings listed above:

The Second Declension

The second declension contains some nouns ending in -ος (mostly masculine and some feminine) and some nouns ending in -ον (neuters). It is declined as follows:

Again, in order to decline a second declension noun, we will simply remove the ending of the genitive singular form (say, from the masculine noun λὀγος, λὀγου, ὁ or the neuter noun ἔργον, ἔργου, τό) thus leaving us with λογ- (or εργ-). Next, all we have to do is attach the appropriate endings for each case. The end result should look something like this:

(Again, be sure to check Hansen and Quinn for special rules concerning accentuation.)

The Article

Greek has a definite article (‘the’ in English) but no indefinite article (‘a’ or ‘an’ in English). The definite article must be formed so as to match the gender, number, and case of the noun it governs:

(M, F and N refer to masculine, feminine and neuter, respectively. This chart, like those above, was pulled from Hansen and Quinn and must be memorized!)

An easy tool for accent memorization: note that the genitive and dative always receive a circumflex, but not other case does. Every other accent is acute, except for the masculine and feminine singular and plural, which receive not accent, only a rough breathing.

Thus ὁ will never be paired with τέχνη and ἡ will never be paired with λόγος, because those articles do not agree with their nouns in gender (ὁ is masculine and ἡ is feminine).

Attributive Position

When the Greeks wanted to modify a noun, they would often place all of the modifiers for a specific noun between the article and the noun. Although we do this in English with most adjectives (‘the delicious ice cream), in Greek all modifiers could be put in this order: genitives (the ‘of the bank’ money, rather than ‘the money of the bank,’ or simply ‘the bank’s money’), prepositional phrases (the ‘under the deck’ beehive), etc. When modifiers (genitives, adjectives and prepositional phrases) are arrayed like this between the article and the noun they refer to, they are said to be in attributive position.

ὁ σοφὸς ἀνήρ - the wise man.

ὁ τοῦ πατρὸς βιβλίον - the ‘of the father’ book, i.e. ‘the book of the father.’

οἱ ὲν τῇ χὠρᾳ ἀδελφοί - the ‘in the country’ brothers, i.e. ‘the brothers in the country’ or ‘the brothers who happen to be in the country.’

Sometimes the article is simply repeated with the modifiers placed after it:

ὁ ἀνὴρ ὁ σοφός - ‘the man, the wise one.’

τὸ βιβλίον τὸ τοῦ πατός - ‘the book, the one that belongs to father.’

οἱ ἀδελφοὶ οἱ ἐν τῇ χώρᾳ - ‘the brothers, the ones in the country.’

And sometimes the Greeks got lazy and just ditched the article before the noun altogether:

ἀνὴρ ὁ σοφός

βιβλίον τὸ τοῦ πατός

ἀδελφοὶ οἱ ἐν τῇ χώρᾳ

All of these constructions are said to use modifiers in the attributive position.

That’s pretty much it! Check sections 16.4 and 17 (pgs. 29 - 30) for some notes on the use of the article (the Greeks used the definite article a lot more than we do) and word order (Subject-Object-Verb is most popular, but it essentially did not matter, aside from attributive position).