Weeks 3: Unit 2

05/09/11 10:24

Greek Verbs

Last week we learned that Greek nouns were made up of three parts: case, number and gender. These parts were distinguished from one another (depending on the noun) by adding endings to a stem - singular vs. plural, nom. vs. acc. and masculine vs. feminine or neuter. Greek Verbs function largely the same way. Like nouns which have a declension and are declined, Greek verbs have a conjugation and are conjugated. Like nouns, verbs can be divided up into parts: person, number, tense (and aspect), mood and voice.

1) Person distinguishes the subject - ‘I’ and ‘we’ are first person, ‘you’ is second person, and ‘he/she/it’ and ‘they’ are third person.

2) Number, as with nouns, distinguishes singular and plural. Like nouns, Greek verbs also had a dual form, for pairs of things.

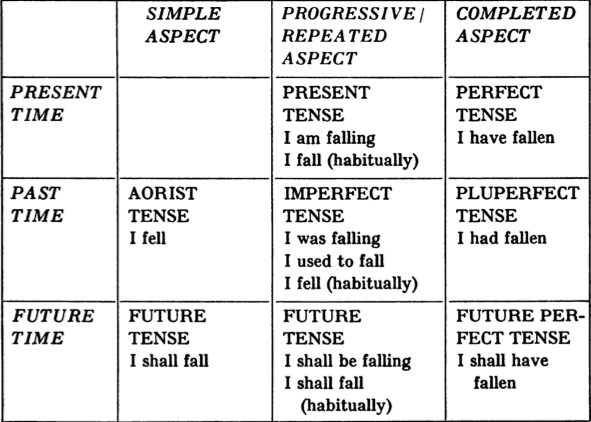

3) Tense tells us about aspect and sometimes time.

3a) Time corresponds to English past, present, and future.

3b) Aspect conveys information about a completed action, a repeated action, or simply the action itself. In English we use helping verbs to denote this:

We baked a pie.

We were baking a pie.

We used to bake a pie.

We had baked a pie.

Note that these sentences all have the same person (1st person) number (plural) and time (past). They differ in aspect. Greek verbs have three forms of aspect: (1) simple, (2) progressive/repeated and (3) completed.

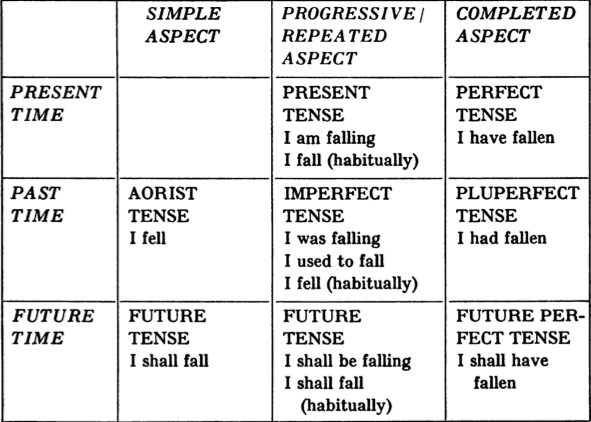

In addition to aspect there are seven tenses of the indicative which must be memorized.

(1) Present describes an action in current time with progressive/repeated aspect. It is always translated ‘I am _____ing’ or ‘I _____.’ For example, ‘I am baking’ or simply, ‘I bake.’

(2) Future is exactly what it sounds like. It can have simple aspect ‘I will bake’ or progressive/repeated ‘I will be baking.’

(3) Perfect tense describes a completed action in present time. It always has simple aspect. It will be translated either ‘I baked,’ or ‘I have baked.’

(4) the Pluperfect tense describes a completed action in past time. It always has simple aspect - ‘I had baked.’

(5) the Future Perfect tense describes a completed action in future time. It also always has simple aspect, and must be translated ‘I will have baked.’

Thus it will be translated ‘I was _____ing,’ or ‘I used to _____,’ or ‘I kept on _____ing.’ so, for example, ‘I was baking,’ I used to bake,’ or ‘I kept on baking.’

(6) and finally the Aorist tense describes an action in past time with simple aspect. It describes an event that has happened and will not be repeated. The closest English rendering would simply be ‘bake.’

This chart from pg. 41 of your text illustrates the various tenses and their uses:

4) Mood tells us whether you’re serious about the statement your making, that is, is the statement, factual, hypothetical, wishful, commanding, etc. There are four moods in Greek, indicative, subjunctive, optative and imperative.

(1) the Indicative is used for factual, simple statements.

(2) the Subjunctive mood is used for a variety of subordinate clauses, which cannot be translated in one particular way every time. With each new subjunctive clause type we learn, we will have to learn a new translation formula.

(3) the Optative mood is also used in a variety of clauses and situations, such that no fixed translation can be given. As the name implies, however, it is largely employed in wishful statements.

(4) the Imperative mood is used for commands: ‘Look over there!’ ‘Freeze!’ and ‘Stop it!’ Might all be rendered in the imperative.

5) Finally, Greek verbs have Voice, that is, whether the subject of the verb performs (active voice) or receives (passive voice) the action.

(1) Active voice verbs can be transitive or intransitive depending on whether or not there is a stated direct object. ‘Rebecca reads.’ would be an active voice sentence with an intransitive verb, because there is no object of the verb ‘reads.’ ‘Rebecca reads a book.’ would be an active voice sentence with a transitive verb - ‘book’ is the direct object of ‘reads.’

(2) Passive voice verbs show that the subject receives the action indicated, and thus are neither transitive nor intransitive. An example might be: ‘the book is read by Rebecca.’

(3) Greek also had a number of Middle voice verbs, which have various changes in meaning, not applicable to any fixed formula. The reader can rest assured, however, that the subject of a middle voice verb always performs the action of the verb. The nuance nevertheless exists that the action somehow returns to the subject - the action is completed by the subject for the subject’s own interests.

Principle Parts

Greek verbs have six principle parts, each gives you the stem necessary to form the different variations of person, number, tense, mood and voice. You might compare these principle parts, which are sometimes regular and sometimes irregular to the regular principle parts of ‘bake’: ‘bake; baked; baked’ and the irregular principle parts of ‘do’: ‘do; did; done.’

Here is a Greek example:

1st Principle part: παιδεύω - ‘I educate; I am educating’ first person singular, present active indicative.

2nd Principle part: παιδεύσω - ‘I will educate’ first person singular, future active indicative.

3rd Principle part: ἐπαίδευσα - ‘I educated’ first person singular, aorist active indicative.

4th Principle part: πεπαίδευκα - ‘I have educated’ first person singular, perfect active indicative.

5th Principle part: πεπαίδευμαι - ‘I had educated’ first person singular, pluperfect active indicative.

6th Principle part: ἐπαιδεύθην - ‘I was educated’ first person singular, aorist passive indicative.

In this class we will identify any set of principle parts by the first form, here παιδεύω.

Present Active Indicative

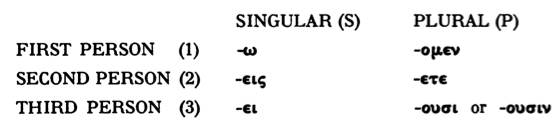

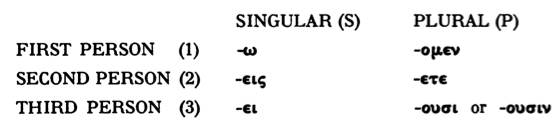

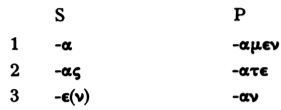

Here are the endings added to the stem to form the present tense indicative:

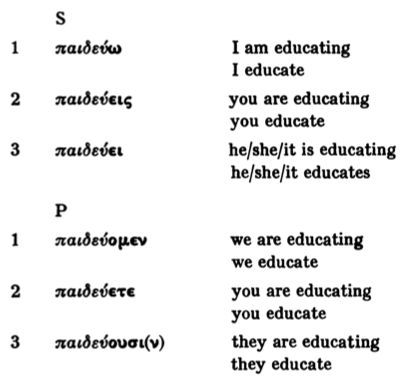

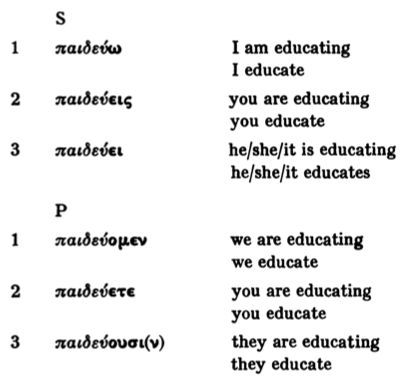

To form any present tense version of the verb παιδεύω, we simply remove the -ω from the stem, leaving παιδευ- and add the above endings.

There are two things you must remember here: first, the Greeks do not need to state the subject of a sentence, it is implied in the ending of the verb. There are separate words for ‘I’ ‘you’ ‘he’ or ‘she’ and ‘they,’ for example, but they do not need to be stated in a sentence. Second, the Greeks have a ‘you’ singular and a ‘you’ plural form, like many Romance languages today and unlike proper English. The plural form is not a polite or formal form of ‘you’ singular. It is, in fact, closest to the Southern expression ‘y’all’ as an appropriate way to address a group of people in the second person.

Imperfect Active Indicative

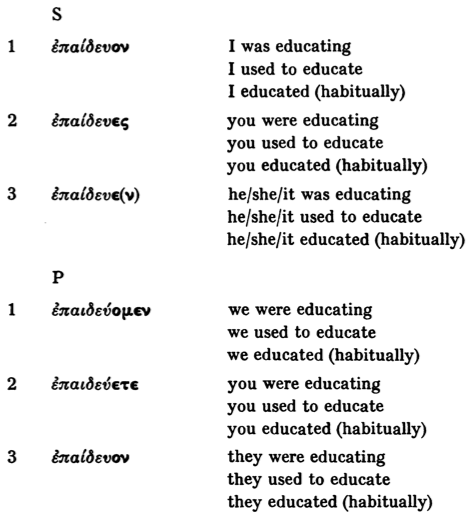

To form the Imperfect, we need to first add a prefix ἐ- to the present tense stem (1st Principle Part) of the verb, and then add the following endings:

Thus, to form the imperfect of παιδεύω, we would drop the -ω from the stem, leaving παιδευ-, and add an ἐ- to the front:

Future Active Indicative

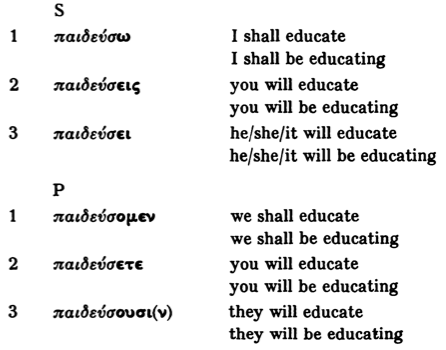

The Future tense employs the same endings as the Present tense, but a different stem. Instead of the 1st Principle part, we’ll use the 2nd Principle part to form the Future.

Thus, to form the imperfect of παιδεύω, we first find the second principle part, παιδεύσω, drop the -ω from the stem, leaving παιδευσ-, and add our familiar Present tense endings:

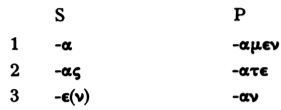

Aorist Indicative Active

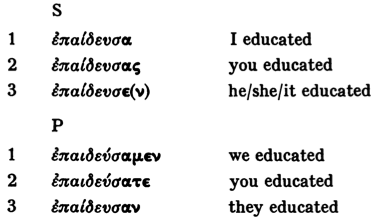

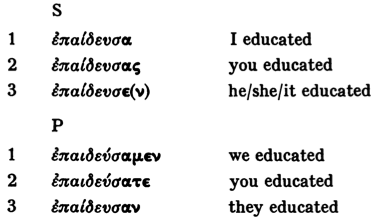

The Aorist tense uses the 3rd Principle part as it’s stem. You’ll notice that it uses the same past prefix ἐ- on the front of the verb as the imperfect, but has a different stem. For παιδεύω it’s ἐπαιδεύσα. We’ll drop the -α ending and add on these special Aorist endings.

When we put these endings on the 3rd Principle part, we get:

Agreement of Subject and Verb

I mentioned above that Greek verbs do not need to state their subject - a subject pronoun is implied in the ending to the verb. Thus ἐπαίδευσα can only mean ‘I educated’ and thus the Greek word for ‘I’ ἐγω is not necessary, but can be included for emphasis. When a subject was stated, such as ὁ ἄνθρωπος παιδεύει - ‘the man educates’ a singular verb must be used with a singular subject, and a plural verb must be used with a plural subject. This is very helpful if you continue to have trouble with case endings: can’t remember which noun is nominative? If the verb is plural, then that should narrow down your options to only plural nouns in the sentence. The Greeks only violate this rule with neuter plural nouns - they can take a singular subject, as they were often envisioned as collective entities: τὰ τῶν θεῶν ἔργα παιδεύει, ‘the deeds of the gods educate.’

Questions

Greek questions could be indicated with a question mark at the end (remember Greek uses a semi-colon ‘;’ to show questions), or with the particle ἆρα at the beginning of the sentence, which was not independently translated.

Infinitives - Present and Aorist Active

All of the verb forms learned thus far are finite - they have person and number endings limiting their meaning to a person or people at a certain time. Infinitives lack these limitations and simply express the action of the verb itself: in English the preposition ‘to’ coupled with the verb performs this function. Thus the infinitive of ‘I bake’ is ‘to bake.’ For now we’ll look at two infinitives, the Present and Aorist.

1) to form the Present Infinitive, add -ειν to the present stem. That’s it. So for παιδεύω, the form is παιδεύειν: ‘to educate.’

2) to form the Aorist Infinitive, remove the augment and the -α ending from the 3rd Principle part, and add an -αι to the end. This is, as usual, short for accentuation purposes and the accent for the Aorist infinitive will always fall on the penult, it is persistent not recessive. Thus the form of παιδεύω is παιδεῦσαι. The accent is circumflex because the ultima is short and the penult is long, and the penult must be accented. The Aorist infinitive has aspect only, and not tense, so it is translated ‘to educate (once and for all).’

Perhaps you’re wondering why the accent changed on the Aorist infinitive from recessive to persistent. ‘I thought verbs had recessive accents!’ Well the infinitive is actually more of a noun than a verb - what we call a gerund in English, and can thus be used as a noun, hence the accent change. An example in English might be ‘Skiing is fun,’ which in Greek would be rendered something like ‘To ski is fun.’ In both examples the verbal form ‘Skiing’ and ‘To ski’ served as the subject and thus a noun.

Uses of the Infinitive

For now the infinitive will only be used with commanding verbs (i.e. I command you to do something). Infinitives can also take a direct object when necessary: τὸν Ὅμηρον κελεύετε τὸν ἀδελφὸν παιδεῦσαι, ‘you command Homer to educate his brother.’

Last week we learned that Greek nouns were made up of three parts: case, number and gender. These parts were distinguished from one another (depending on the noun) by adding endings to a stem - singular vs. plural, nom. vs. acc. and masculine vs. feminine or neuter. Greek Verbs function largely the same way. Like nouns which have a declension and are declined, Greek verbs have a conjugation and are conjugated. Like nouns, verbs can be divided up into parts: person, number, tense (and aspect), mood and voice.

1) Person distinguishes the subject - ‘I’ and ‘we’ are first person, ‘you’ is second person, and ‘he/she/it’ and ‘they’ are third person.

2) Number, as with nouns, distinguishes singular and plural. Like nouns, Greek verbs also had a dual form, for pairs of things.

3) Tense tells us about aspect and sometimes time.

3a) Time corresponds to English past, present, and future.

3b) Aspect conveys information about a completed action, a repeated action, or simply the action itself. In English we use helping verbs to denote this:

We baked a pie.

We were baking a pie.

We used to bake a pie.

We had baked a pie.

Note that these sentences all have the same person (1st person) number (plural) and time (past). They differ in aspect. Greek verbs have three forms of aspect: (1) simple, (2) progressive/repeated and (3) completed.

In addition to aspect there are seven tenses of the indicative which must be memorized.

(1) Present describes an action in current time with progressive/repeated aspect. It is always translated ‘I am _____ing’ or ‘I _____.’ For example, ‘I am baking’ or simply, ‘I bake.’

(2) Future is exactly what it sounds like. It can have simple aspect ‘I will bake’ or progressive/repeated ‘I will be baking.’

(3) Perfect tense describes a completed action in present time. It always has simple aspect. It will be translated either ‘I baked,’ or ‘I have baked.’

(4) the Pluperfect tense describes a completed action in past time. It always has simple aspect - ‘I had baked.’

(5) the Future Perfect tense describes a completed action in future time. It also always has simple aspect, and must be translated ‘I will have baked.’

Thus it will be translated ‘I was _____ing,’ or ‘I used to _____,’ or ‘I kept on _____ing.’ so, for example, ‘I was baking,’ I used to bake,’ or ‘I kept on baking.’

(6) and finally the Aorist tense describes an action in past time with simple aspect. It describes an event that has happened and will not be repeated. The closest English rendering would simply be ‘bake.’

This chart from pg. 41 of your text illustrates the various tenses and their uses:

4) Mood tells us whether you’re serious about the statement your making, that is, is the statement, factual, hypothetical, wishful, commanding, etc. There are four moods in Greek, indicative, subjunctive, optative and imperative.

(1) the Indicative is used for factual, simple statements.

(2) the Subjunctive mood is used for a variety of subordinate clauses, which cannot be translated in one particular way every time. With each new subjunctive clause type we learn, we will have to learn a new translation formula.

(3) the Optative mood is also used in a variety of clauses and situations, such that no fixed translation can be given. As the name implies, however, it is largely employed in wishful statements.

(4) the Imperative mood is used for commands: ‘Look over there!’ ‘Freeze!’ and ‘Stop it!’ Might all be rendered in the imperative.

5) Finally, Greek verbs have Voice, that is, whether the subject of the verb performs (active voice) or receives (passive voice) the action.

(1) Active voice verbs can be transitive or intransitive depending on whether or not there is a stated direct object. ‘Rebecca reads.’ would be an active voice sentence with an intransitive verb, because there is no object of the verb ‘reads.’ ‘Rebecca reads a book.’ would be an active voice sentence with a transitive verb - ‘book’ is the direct object of ‘reads.’

(2) Passive voice verbs show that the subject receives the action indicated, and thus are neither transitive nor intransitive. An example might be: ‘the book is read by Rebecca.’

(3) Greek also had a number of Middle voice verbs, which have various changes in meaning, not applicable to any fixed formula. The reader can rest assured, however, that the subject of a middle voice verb always performs the action of the verb. The nuance nevertheless exists that the action somehow returns to the subject - the action is completed by the subject for the subject’s own interests.

Principle Parts

Greek verbs have six principle parts, each gives you the stem necessary to form the different variations of person, number, tense, mood and voice. You might compare these principle parts, which are sometimes regular and sometimes irregular to the regular principle parts of ‘bake’: ‘bake; baked; baked’ and the irregular principle parts of ‘do’: ‘do; did; done.’

Here is a Greek example:

1st Principle part: παιδεύω - ‘I educate; I am educating’ first person singular, present active indicative.

2nd Principle part: παιδεύσω - ‘I will educate’ first person singular, future active indicative.

3rd Principle part: ἐπαίδευσα - ‘I educated’ first person singular, aorist active indicative.

4th Principle part: πεπαίδευκα - ‘I have educated’ first person singular, perfect active indicative.

5th Principle part: πεπαίδευμαι - ‘I had educated’ first person singular, pluperfect active indicative.

6th Principle part: ἐπαιδεύθην - ‘I was educated’ first person singular, aorist passive indicative.

In this class we will identify any set of principle parts by the first form, here παιδεύω.

Present Active Indicative

Here are the endings added to the stem to form the present tense indicative:

To form any present tense version of the verb παιδεύω, we simply remove the -ω from the stem, leaving παιδευ- and add the above endings.

There are two things you must remember here: first, the Greeks do not need to state the subject of a sentence, it is implied in the ending of the verb. There are separate words for ‘I’ ‘you’ ‘he’ or ‘she’ and ‘they,’ for example, but they do not need to be stated in a sentence. Second, the Greeks have a ‘you’ singular and a ‘you’ plural form, like many Romance languages today and unlike proper English. The plural form is not a polite or formal form of ‘you’ singular. It is, in fact, closest to the Southern expression ‘y’all’ as an appropriate way to address a group of people in the second person.

Imperfect Active Indicative

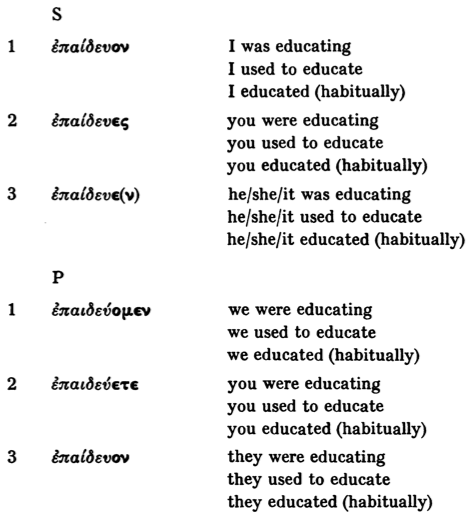

To form the Imperfect, we need to first add a prefix ἐ- to the present tense stem (1st Principle Part) of the verb, and then add the following endings:

Thus, to form the imperfect of παιδεύω, we would drop the -ω from the stem, leaving παιδευ-, and add an ἐ- to the front:

Future Active Indicative

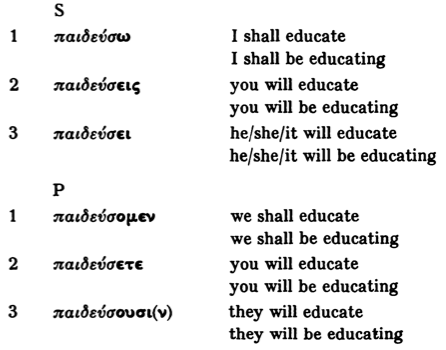

The Future tense employs the same endings as the Present tense, but a different stem. Instead of the 1st Principle part, we’ll use the 2nd Principle part to form the Future.

Thus, to form the imperfect of παιδεύω, we first find the second principle part, παιδεύσω, drop the -ω from the stem, leaving παιδευσ-, and add our familiar Present tense endings:

Aorist Indicative Active

The Aorist tense uses the 3rd Principle part as it’s stem. You’ll notice that it uses the same past prefix ἐ- on the front of the verb as the imperfect, but has a different stem. For παιδεύω it’s ἐπαιδεύσα. We’ll drop the -α ending and add on these special Aorist endings.

When we put these endings on the 3rd Principle part, we get:

Agreement of Subject and Verb

I mentioned above that Greek verbs do not need to state their subject - a subject pronoun is implied in the ending to the verb. Thus ἐπαίδευσα can only mean ‘I educated’ and thus the Greek word for ‘I’ ἐγω is not necessary, but can be included for emphasis. When a subject was stated, such as ὁ ἄνθρωπος παιδεύει - ‘the man educates’ a singular verb must be used with a singular subject, and a plural verb must be used with a plural subject. This is very helpful if you continue to have trouble with case endings: can’t remember which noun is nominative? If the verb is plural, then that should narrow down your options to only plural nouns in the sentence. The Greeks only violate this rule with neuter plural nouns - they can take a singular subject, as they were often envisioned as collective entities: τὰ τῶν θεῶν ἔργα παιδεύει, ‘the deeds of the gods educate.’

Questions

Greek questions could be indicated with a question mark at the end (remember Greek uses a semi-colon ‘;’ to show questions), or with the particle ἆρα at the beginning of the sentence, which was not independently translated.

Infinitives - Present and Aorist Active

All of the verb forms learned thus far are finite - they have person and number endings limiting their meaning to a person or people at a certain time. Infinitives lack these limitations and simply express the action of the verb itself: in English the preposition ‘to’ coupled with the verb performs this function. Thus the infinitive of ‘I bake’ is ‘to bake.’ For now we’ll look at two infinitives, the Present and Aorist.

1) to form the Present Infinitive, add -ειν to the present stem. That’s it. So for παιδεύω, the form is παιδεύειν: ‘to educate.’

2) to form the Aorist Infinitive, remove the augment and the -α ending from the 3rd Principle part, and add an -αι to the end. This is, as usual, short for accentuation purposes and the accent for the Aorist infinitive will always fall on the penult, it is persistent not recessive. Thus the form of παιδεύω is παιδεῦσαι. The accent is circumflex because the ultima is short and the penult is long, and the penult must be accented. The Aorist infinitive has aspect only, and not tense, so it is translated ‘to educate (once and for all).’

Perhaps you’re wondering why the accent changed on the Aorist infinitive from recessive to persistent. ‘I thought verbs had recessive accents!’ Well the infinitive is actually more of a noun than a verb - what we call a gerund in English, and can thus be used as a noun, hence the accent change. An example in English might be ‘Skiing is fun,’ which in Greek would be rendered something like ‘To ski is fun.’ In both examples the verbal form ‘Skiing’ and ‘To ski’ served as the subject and thus a noun.

Uses of the Infinitive

For now the infinitive will only be used with commanding verbs (i.e. I command you to do something). Infinitives can also take a direct object when necessary: τὸν Ὅμηρον κελεύετε τὸν ἀδελφὸν παιδεῦσαι, ‘you command Homer to educate his brother.’